Burnout, disillusionment, boredom – there are lots of reasons why people leave the music business. We spoke to four professionals who have moved on from the industry to tell us about their reasons for leaving.

A career in the music industry is often seen as highly desirable and no doubt this can be one of the most fulfilling and fun industries to work in. But the truth is that it can also be a tough and unforgiving business that requires talent, hard work, commitment, resilience, more hard work as well as plenty of contacts and lots of luck too.

For this month’s Long Read, we wanted to find out why people leave the music business. We asked four former music industry pros to tell us their stories.

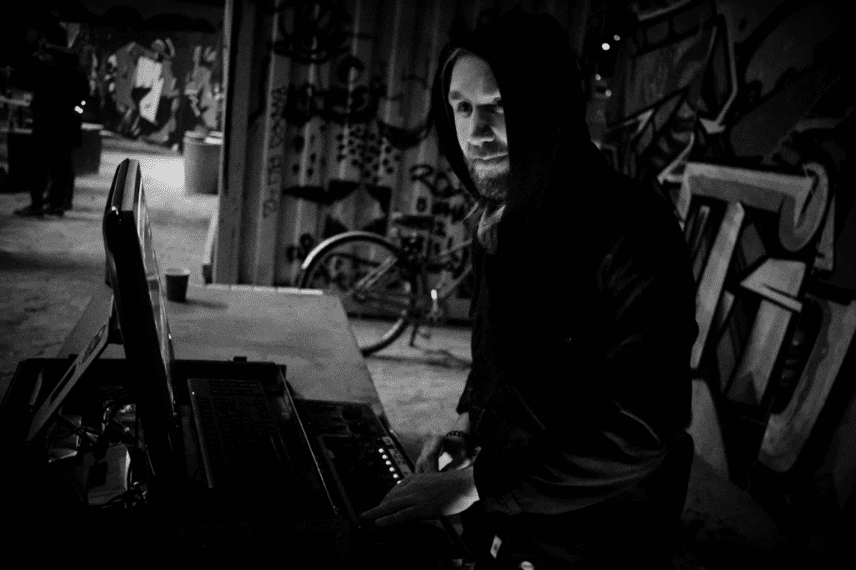

Tom Wainwright: Hacienda Resident DJ

Tom Wainwright was a Saturday night resident DJ at Manchester’s Hacienda from 1991 to 1996 and played big events/clubs at the time like Shindig, Renaissance, Ministry of Sound and Gatecrasher. DJing was his full-time job between 1991 and 2004 and he reached #63 in DJ Mag’s Top 100 DJs poll before re-training as a solicitor. Tom takes up his story:

“My DJ career seemed to end gradually by mutual agreement. I’d had enough of it, but more importantly, it had had enough of me. I did lots of really good gigs, but I did a lot more treadmill gigs that in truth weren’t that great for me or the people in attendance. People can tell quite quickly if your heart’s not in it anymore. As a result, you no longer get booked for the good gigs, so you’re doing bad gigs you’re not that enthusiastic about, and soon you’re locked into a downward spiral of indifferent performances to equally indifferent punters. For a long time, all that mattered in my life was clubs and DJing, but that grind knocked the passion out of me. Then you start a “proper” job and you realise what grind actually is.

Over the years there were various ups and downs. Sometimes I’d be flavour of the month, and other times the phone wouldn’t ring for weeks. In about 2003 I was in one of the downs. I decided that the precarious nature of self-employment wasn’t for me anymore and I didn’t want to be on the M62 eating Ginsters at 4 am for the rest of my working life. I enrolled on a law conversion course with the aim of becoming a solicitor. A surprising number of DJs have made this unnatural career progression.

That said, I didn’t make a conscious decision to stop. There wasn’t a “this is my last gig” moment. I didn’t start refusing gigs but I didn’t pursue them either. By the time I qualified as a solicitor the DJ diary was basically empty.

“What’s quite weird is that I think about having been a DJ pretty much every day of my life and it largely defines my sense of who I am, but I don’t really miss it either.”

Occasionally I get into the office and think “how did this happen?”, but in the main not really. I staved off the rat race until my mid-30s, (generally) had the respect of my peers, and had lots of fun travelling the world getting paid well in the process. Many people would’ve given their right arm for that.

Would I rather be a DJ than a solicitor? The answer is yes. What’s quite weird though is that I think about having been a DJ pretty much every day of my life and it largely defines my sense of who I am, but I don’t really miss it either. The law is fairly boring but so are most jobs.

Over the last few years, I’ve been doing the odd gig on the retro circuit and I really enjoy those. The Hacienda put me on at one of their Warehouse Project events the other week and it was exhilarating. Going to gigs now, is like visiting my old life without having to worry if they’ll pay the mortgage or not. If a gig goes well then that’s great. If it doesn’t then (apart from the two hours of ritual humiliation while I’m doing it) it doesn’t really matter in the way it used to. In a way that’s quite liberating.”

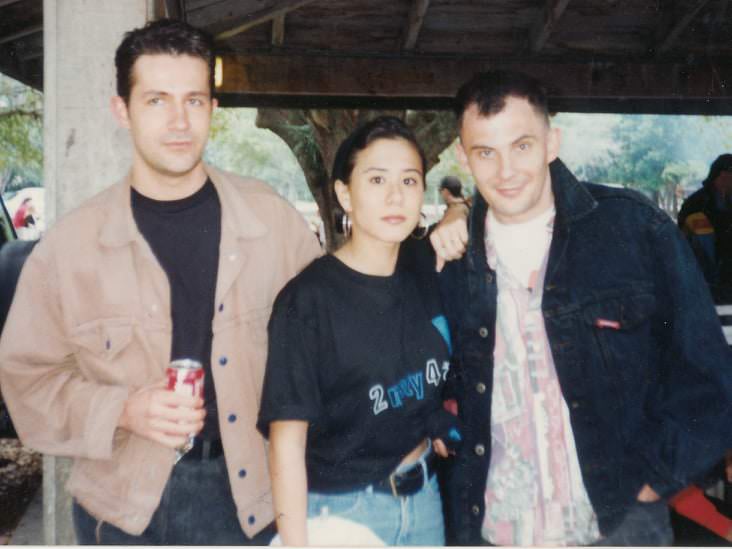

Chris Day: Producer, Remixer, DJ, A&R

Chris Day was one half of 90s UK house act Chris & James, one-third of The Delorme, an international DJ, remixer and producer, writer for Mixmag as well as A&R for Stress Records.

“I left the music industry just after the millennium. I became very bored with the way the scene had gone from being eclectic and a mix of sounds/genres/styles/tribes, to much more single genres. I also became a parent in late 1998, so I didn’t want to be an absent father! I have no regrets at all. I miss the early 90s Balearic scene and societal attitude shifts, but not the music business itself.

After spending 15 years as a house husband bringing up the kids, I now coach football at a high level and love (nearly every) minute of it – no regrets!”

Christina Rosetti: Plugger / Writer

Christina Rosetti worked for Capitol-EMI as a local uni-college promotions rep in 1989-1991 in western Massachusetts. After graduating from university she started working for the number one independent dance music promoter in America, speaking to Billboard, radio mix shows, and important local DJs all over the country to get them to play and chart the records they were promoting. She also wrote a techno column for their monthly magazine.

“I left in 1992. I was working 10-12 hours a day, plus having to go out to clubs 2-4 nights a week (when you have to go to clubs for work it’s not much fun) and I was making only $15,000 a year. And believe me, that wasn’t enough money to live on in NYC, even back then! I looked at the people in my business that I admired that worked at the record labels and realised it was pretty much almost all men. There was Iris Dillon at Virgin, and Lesley Doyle at Elektra, and that’s it. The rest was just a big sausage-fest. The dance music business was toxic and incestuous at the time.”

“I was overworked, tired, and miserable. And the worst part was that I started hating music! I got into this because I loved music. I started DJing in 1983, and from that time I was focused on working in the (dance) music business. I quit the promotions company and was temping at a bank to earn some cash. I planned on applying for jobs at the record labels in January when they usually started hiring. However, the bank I was temping at offered me the chance to get into their graduate training programme. I realised that just because I loved music, it didn’t mean that I needed to work in the music business. I realised that I could work at the bank and continue DJing part-time and buy all the music I wanted!

The music biz is a completely different place than when I was in it pre-internet. Promotions and retail have changed almost beyond recognition. But there will always be a place for people with a good ear, who can recognise the next big thing.”

Pawel Rogowski: Non Profit Co-Founder

Pawel Rogowski co-founded and co-created FEUM, the Association for Electronic and Underground Music in Denmark, a non-profit organisation aimed to create space for quality electronic music and responsible nightlife. Pawel left the industry last year:

“I left in September 2020 after many months of slow burnout. I felt that creating events is a source of constant hustle and struggle, with authorities, co-creators, funding. The idea and passion for creating something unique and redefining what a music/club event can be, and what role does it serve turned into a process of repetition and simply “throwing parties”. Also within our group, we couldn’t agree on which direction our union should take and what responsibilities we have before our followers.”

“The fact that it is hard to work around electronic music and nightlife in Denmark was an important factor, not to mention that all our events and bookings have been cancelled for months due to the lockdown. It felt for me that working with art and music involved too many variables that I couldn’t influence and instead of it being a source of creativity, it had me feeling helpless and really burnt out. In the end, I would rarely enjoy the events I had created myself.

Oddly enough, I stopped going out and partying since I left. I go out sporadically and my focus shifted back to what drew me into this culture first – digging for new sounds and artists, discovering new avenues of electronic music just for the pure pleasure of listening to it. All of the above would have been easier if working with culture and alternative genres (though it’s hard to call techno or electronic music underground anymore) would have been seen as a legitimate and valuable occupation.

However, at the same time, that’s how this culture appeared in the first place, through liberating from oppression, radical self-expression, to illegal substances and raves. I still believe that struggle and pain are an indispensable part of the electronic music scene, the beautiful balance between oppressive and meditative state.”

Thank you to all our contributors.