Composer and field recordist Alice Boyd has combined biological signals with analogue synthesis to create an enchanting EP that begs the listener to consider their status as a terrestrial.

The sun is shining over Crystal Palace Park when I meet Alice Boyd, and we sit outside to enjoy its rays. Locals of all ages and species are doing the same, and the recording of our interview reveals a supporting cast of birds, insects, and dogs. Squirrels rustle in the boughs of trees overhead. A few metres away, the rack I’ve secured my bicycle to is shaped like a row of oak trees, painted forest-green with steel branches to slip your lock through. It’s a pleasant, if unremarkable, location – a respite from South London’s traffic thoroughfares and acreage of brick and concrete.

But it’s a suitable setting to explore Boyd’s new EP, From The Understory, released to coincide with Earth Day, on the 22nd April 2023. The record explores humanity’s relationship with the natural world – it seriously questions the fallacy that humans are so far removed from their fellow residents on earth. The tracks move unhurriedly, each note taking the shape of a fern frond unfurling to meet the sun. Intoxicating choral vocals layer and shift, hushed then clear, speaking to the listener and through the listener as they sculpt indie-folk harmonies onto a bed of glacial electronics.

“There is this distinction, in Western culture, between human and everything else. There’s that hierarchy – we are constantly interacting with the world around us, yet not questioning what nature means. Over 50% of us is bacteria and we’re constantly in flow: whether it’s the food we eat, or the bacteria within us, or the clothes we’re wearing”, she explains.

Boyd’s desire to wear away at these socially-constructed divisions is reflected in more than just the concepts that inspired the album, but also in its very sonic fabric. Taking part in an artists residency at The Eden Project, she was able to record biodata from the abundant plantlife — say, movement of liquids and salts across the interior of a leaf body — and later feed these signals into her suite of analogue synthesisers as the seeds for her tracks.

“The understory is a layer of the tree canopy”, she explains. It’s the part of the forest between the floor and the overstory, which is the top later. Essentially, it’s the part which they share with humans. “The EP is very much about this human relationship with the environment and our roles within it. So I wanted the title of it to be the story from where we stand”.

Her emphatic rejection of human exceptionalism reminds me of the ‘Terrans’ described by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, the influential Brazilian thinker. It’s a term he uses to describe some people, identifying them as terrestrials – dwellers of the earth, much the same as any flora or fauna. It’s distinct from ‘Humans’, which is a group which distinguishes itself from other lifeforms so that they may trample over them more easily.

Viveiros de Castro goes on to describe a ‘gaia war’ that is occurring at this moment wherein the earth, made fragile through human interventions such as climate change, becomes like a vengeful god, and Terrans enter into conflict with Humans for the planet’s fate.

If not drawing such stark divisions, Boyd is certainly trying to give a voice to plants so that we may consider them – even identify with them. And what better language than music? She uses a technology called bio-sonification, which allows data points to be extracted from a plant’s ever-changing structure and piped into a synthesiser.

Boyd is certainly trying to give a voice to plants so that we may consider them - even identify with them

Boyd explains: “you plug in two electrodes onto plants leaf, and it records changes in conductivity, which changes as water and salt concentration changes in response to light or temperature when they’re photosynthesizing. And it takes that wave of data and applies it to MIDI.

So it’s sort of like the plant is a random melody generator. I found it a really playful way to make a song. I used it as the basis for some of the songs on the EP, and then on other songs, I use it for some background textures.”

So, the human artist interprets the data they have measured from the plant?

“I phrase it as: it’s music made with plants… at its core, this technology just shows that plants are active. And even there is this humankind of fingerprint on it, showing that when you put the electrodes on plant — something that looks fairly still — is spilling out these melodies, and I think that can be quite a powerful.”

She continues, “There are these ideas of charisma and the different types of charisma that you have, like aesthetic charisma, where it’s like: oh a dog, it’s so cute, I love it! So maybe this technology also gives plants like a couple of extra points on the charisma scale, because they now can they can make sick beats”.

We both laugh, and I conjure the thought of a red-eyed succulent in a smoky room, hunched low over an sampler. In fact, it was a Korg Minilogue, a Prophet-6, and a Moog Sub 37 which the plants were able to play – sadly they stayed in situ at The Eden Project, rather than getting busy in the studio. At the same time, I can’t help but reflect on the most charismatic of animals, the ‘charismatic megafauna’ of elephants, tigers, panda bears, and the like. Despite their name-brand recognition, they’re not doing so well in the conservation stakes. One can hope that the improved street cred of Boyd’s plants will serve them better.

MIDI Sprout, the first bio-sonification project to hit the mainstream grew out of a label called Data Garden who created projects that combined music, technology, and plant life. In 2012 they held an installation at the Philadelphia Museum of Art with the first micro conductivity device, calling it the ‘Data Garden Quartet’. It was such a success that they created a commercial product that was enormously successful.

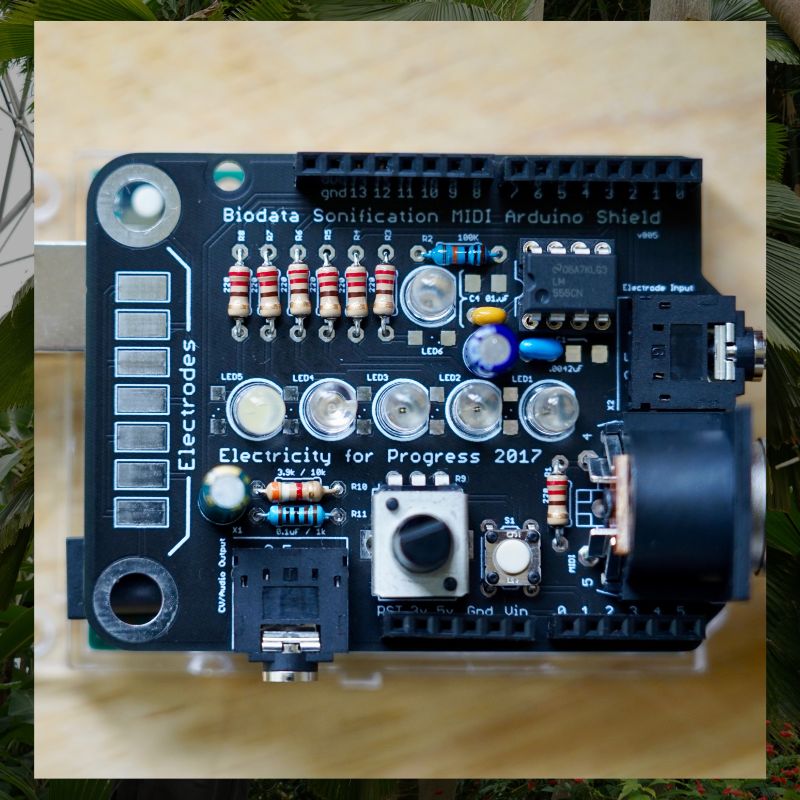

Crucially, they made the code and circuits available to the public (see it here on GitHub), allowing for projects like Electricity for Progress to create an open-source version. This barebones offering is ideal for working musicians who wish to use bio-sonification without investing in a branded product aimed at home listeners. Electricity for Progress’ iteration is the one that Alice Boyd built and uses, soldering the Arduino device in the first Covid lockdown when she saw her usual work in theatre in a puff of smoke.

“I got really interested in people who were making art with environmental data or some kind of input from the environment. There’s an artist called John Luther Adams, who has previously made an installation that takes data from the Northern Lights, and tectonic activity data and made a live sound installation that responds to those like live data streams.”

I wanted to ask Alice about the responsibility she felt to both her leafy collaborators and the environmental movement as a whole. How does she draw attention to her music, without being co-opted by companies or institutions who want to use her environmental message as a form of greenwashing?

The plants had huge differences between them. The Sea Hibiscus I remember so much because that was a really nice bed to use. It was less frequent and played the same kind of notes, whereas some of them were all over the place!

“My performance at The Eden Project last January was part of a project called ‘Eden Universe’, where the Eden Project had got funding from the Department for Culture, Media, and Sport to be one of test sites for installing 5g, to see how it improved engagement with what they were doing… I think it’s important to debate things and to question them. But it’s tricky! I think there is something to be said about working with the technologies we have and seeing what good they can do… while being aware of all the negatives as well”.

So it’s a trade off of telling the important stories, while engaging in good faith with unavoidable mechanisms – such as government bodies or businesses? She thinks for a moment. “It’s that idea of retreat and purism – if you’re never going to work with a big institution or something… I don’t know”. She trails off, leaving unspoken the image of an artist toiling in obscurity.

Would she work with an oil company, if it meant she could amplify the ‘right’ message?

“I think it’d be tricky, but I would say no. I’ve had to say no to a fast fashion brand already… I asked them what are your current policies? What is this actually for? Is there any kind of link to climate change or sustainability? Just to see if they were thinking about it. And they were like, no, it’s just for our summer campaign. I was like – goodbye!”.

Changing the topic, we discuss which plants made an impact on the record. She tells me about the Sea Hibiscus, Bamboo, and Periwinkle that had unique characters. “They definitely had quite huge differences between them. The Sea Hibiscus I remember so much because that was a really nice bed to use. It was less frequent and played the same kind of notes, whereas some of them were all over the place!”

Boyd has transitioned the record from a studio project (which involved a choir of female and non-binary singers, as well as the leafy ensemble) to a live band. They played their first gig in London’s Avalon Cafe in April. Still, she finds it hard to pin down anything like genre. “It kind of takes a few different influences. It has moments that sound quite folksy with the harmonies. Then there’s a couple of tracks that are more ambient and electronic. With the live setup, it can lean more towards indie.”

Despite bearing fruit only recently, this is a project that has been in the works for many years. Since then, Boyd has been developing more techniques to invite the sounds of growth and terrain into her soundworld. Lately, she’s been working with hydrophones, ie. underwater microphones, for a pond-based project in Norfolk with UCL.

“I think a lot of people dismiss ponds. But when they’re well managed they can be more biodiverse than lakes or rivers. We used hydrophones to record under the surface of the ponds. It was nuts to hear the sounds that come out of there. Both the insect world — suddenly hearing this cacophony – and also the sounds of plants photosynthesizing. You actually hear the air bubbles coming from the aquatic plants underneath. And they sound like synthesizers. They don’t sound like bubbles, they sound like weird arpeggiators! It sounds like such an alien world.

The thing I’m really interested in is seeing if there are these hidden worlds, things that humans don’t instantly perceive or that are outside of human hearing, and finding ways to record them and translate them for people to kind of experience”.

Alice Boyd From The Understory is out now on Bandcamp.

Find Alice Boyd on Instagram.