An in-depth discussion with the Ghostly International co-founder about his teenage discovery of electronic music, moving from the studio to the stage and why he feels compelled to make music.

The release of Matthew Dear’s fifth studio album Beams this summer confirmed the Ghostly co-founder’s transformation from microhouse master to avant-garde pop star. It’s a process that began in earnest with 2007’s Asa Breed LP – which marked a distinct shift away from Dear’s previous work – and continued with 2010’s exceptional Black City.

Ahead of the arrival of his live tour in the UK, Matthew spoke to us earlier this week by phone from his hotel room in Utrecht. In the short time we spent chatting with him it was clear that Dear is obsessive about music in the way that most great artists are, but also that he’s able to take a step back and articulate his own relationship with his art.

In this revealing interview he opens up about his compulsion to make music in order to express his state of being, explains how he approaches the challenges of transferring electronic music from the studio to the stage and talks in detail about the excitement of discovering dance music as a teenager, having moved from Texas to Detroit at the age of 16.

Attack: Your live tour arrives in the UK this week, including a huge gig at Fabric in London on Wednesday. I wanted to start off by talking about the transition from the studio to the stage. How do the two relate to each other for you?

Matthew Dear: It’s a bit tricky, you know, because obviously the studio experience is so contained and controlled, but when you bring it to the live experience there’s a lot you have to let go. You really have to try to re-form everything and allow the musicians and the band to take over – whereas a lot of things are happening with samplers, synthesisers and drum machines in the studio.

It’s a delicate balance, but that’s what rehearsals are for. I have the band come visit my studio and we just hang out for a few weeks at a time, make a lot of food, wake up, practise, go to sleep and then do it all over again the next day. It becomes kind of a shared experience and quite fun, actually, when it’s all said and done.

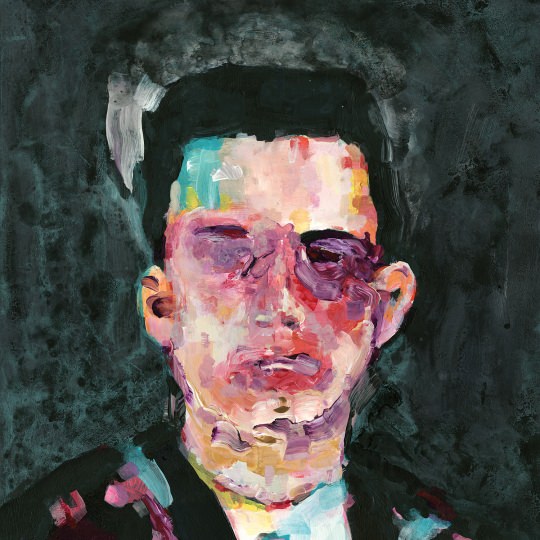

Beams cover art by Michael Cina

I think one of the difficulties a lot of electronic artists experience when they move to live performances is that the rigidity of the structures of their music can limit them. Is that something which you’ve made an effort to avoid?

Absolutely. It’s not to say that what I’m doing now isn’t sequenced – there’s definitely a locked order to what we’re doing on stage – but the fact that we leave so much out. We leave room for the live drum set, the live bass, the guitar and the percussion.

The last thing I want to do is go out there with the tracks from the album and just sing over them. We could easily use an electronic drum kit which is triggering sounds from the album or the bass player could be playing a keyboard with the same samples from the album but I like to be different and it makes it more fun for myself as well as the audience.

Is there a lot of flexibility in the set for you to interpret songs in different ways on different nights and play something unique every time?

It’s maybe 20% flexibility and 80% pre-determined rehearsal. I like to use a lot of loops in between songs, so we give ourselves the opportunity to be a bit more freeform and imaginative during the transitions and to do something new with them each night.

To what extent do you also have to think about the visuals of the show?

Quite a bit. Nobody’s making these decisions for me. Unfortunately, touring with the outfit we’re doing now – well, not unfortunately – I decided to put most of my investment into the sound, how much gear we could bring out and the musicians on stage. So there’s no big visual spectacle behind us on this tour, but for the most part we do small things. We decorate the stage with roses. The cloth banners which we use as a backdrop are panels from the inside of the album cover. Little things like this that just kind of draw the visual scape into one feeling – it’s about the album and the way the album feels to me. There’s no crazy light show or anything!

How about your own performance on stage and the way you interact with the crowd? Do you make any conscious effort to make that visually interesting in any way?

Absolutely, but I’ve always been very careful not to force it.

Of course.

I didn’t ever want to come out and just do something very theatrical that wasn’t in me. It took a while but now I’ve found a way I guess just to relinquish myself into the music and let movement and music flow through me and translate. You definitely allow yourself to go somewhere – not just myself but the other members of the band.

You have to kind of disconnect from the natural world as soon as you step on stage and understand that you’re on a pedestal of sorts for that 75 minutes. You have to do something which allows people to channel themselves through you. I’m feeding off that energy of the crowd as well as giving energy back. I definitely try to do different things to what I would be doing normally in the studio I guess.

I think it’s quite an interesting time at the moment in terms of people’s perceptions of artists, producers, pop stars, DJs and all these overlapping, quite vaguely defined roles. Do you see what you do in each of your guises – like on the stage as opposed to in the studio – as being something different, or is it all part of something bigger to you?

For me I don’t want to have any role or limitations. I see it as… The human experience is wide open. I can do many many things, so the live band performance is just part of that greater experience. Is it connected inherently to the studio stuff or the version of me that I am in the studio? It is by the music, of course, but the guy that’s standing on stage singing, jumping around, playing guitar – I don’t enter that headspace in the studio.

The studio’s far more – not refined, but it’s far more internal and immersive. All the jumping around and the craziness happens inside my head when I’m singing in the studio. I don’t need the physical release to feel that way. Therefore it totally takes on a different character, even. There’s a totally different personality when you’re on stage. In that sense they’re two totally different worlds but they are attached by the music.

That question of the environment informing your artistic output is really interesting. I wanted to talk a little bit about how your environment has affected your music. You moved from Texas to Michigan when you were a teenager, right?

That’s correct.

I think we have this stereotype that anyone who moves anywhere near Detroit immediately starts listening to techno, which is obviously ridiculous, but I wanted to know how much exposure you had to electronic music in Texas and how that changed when you moved north.

In Texas I had just gotten into my brother’s record collection. It was really strange. A lot of what I got at an early age was this kind of crazy European dance music – Erasure, New Order, then a little bit more industrial like Front 242 and Nitzer Ebb. Growing up in Texas it was very strange for me to have access to all of this music but somehow he had had friends who’d turned him on to this stuff. I knew of electronic music to a certain degree. He took me to a Depeche Mode concert when I was 14. That was one of my first experiences of live music. To me drum machines and synthesisers were kind of always just a part of music. Then I was also listening to a lot of rock music – Texas is pure rock and country. So I had all these influences.

When I moved to Detroit at 16 I definitely liked electronic music of some sort but I had no idea that there was a scene. I didn’t know about DJ culture or the beginnings of all the rave stuff that was happening in England. Of course not everybody that moves to Michigan falls in love with techno – we’re still considered the underdogs and the odd ones out – but it’s far more electronic-based. Drum machines and synthesisers are far more accepted there on popular radio than they were in Texas, so immediately I fell in love with Detroit radio.

I used to listen a lot to this radio station called WJLB 97.9 and back then after about ten o’clock at night on the weekends they’d play what was referred to as ghettotech or booty music, which is like fast-paced dance music from Detroit. People like DJ Assault and Disco D, who became very influential for us as a label. A lot of them would sample things like ‘Shari Vari’ and a lot of the original classic Kraftwerk stuff and turn it into something new.

So immediately you’re inundated with this when you live in Detroit and you realise that this music is attached to a nightlife. It’s attached to some dance club that’s happening right now that you’re not at. That experience was kind of intriguing. You start going looking for dark alleys and seeing what’s behind closed doors. You see flyers lying around in music shops that say: Yo, go see this DJ, that DJ, Atomic Babies, Crystal Method… All this stuff was happening. Midnight, McNichols warehouse, Detroit…

So all this hit me at once. That’s when I started following that path. Then immediately after I went to my first party at this abandoned warehouse in Detroit I guess it was the quintessential light bulb that goes off over a lot of our heads when we realise, this culture’s for me.