In the first installment of a two-part story, we look at the evolution of vocal synthesis, from primitive speech-mimicking machines to modern software vocoders.

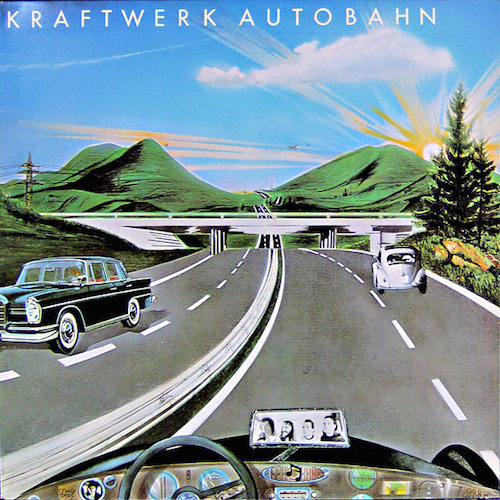

It all started in 1974 with four Germans singing about a roadway. With its Beach Boys-style pop vocals and Minimoog bassline, ’Autobahn’ was a surprise hit single. It was also one of the first electronic songs to feature a vocoder in a prominent role. What was this strange, other-worldly warbling? The novelty of hearing a machine ‘sing’ must have been shocking to listeners in the 1970s.

Of course, Kraftwerk’s custom-made vocoder used on ‘Autobahn’ wasn’t the first instance of vocal synthesis. The history of mechanically replicating human speech goes back much further than that, hundreds of years in fact. But for electronic music, it’s the patient zero that went on to infect thousands with the desire to sing like a machine.

Vocal synthesis has a long and fascinating history, incorporating speech synthesis, telecommunications, synthesizers, and computer software. In this, the first in a two-part series, we’ll examine the history of speech synthesis and vocoders.

Vocal Synthesis: An Evolution From Speech Synthesis To Musical Synthesis

Before you can run you need to learn to walk. And before you sing, you learn to talk. The same thing happened with speech synthesis. Before we could coax machines into singing, we had to teach them to speak. This first happened a surprisingly long time ago. As far back as the 16th century, people began designing mechanical devices to replicate human speech. While these were primitive attempts, they eventually led to more robust experiments, such as the Euphonia, a contraption with a piano keyboard for triggering sounds, bellows for pumping air, and a mechanical mouth.

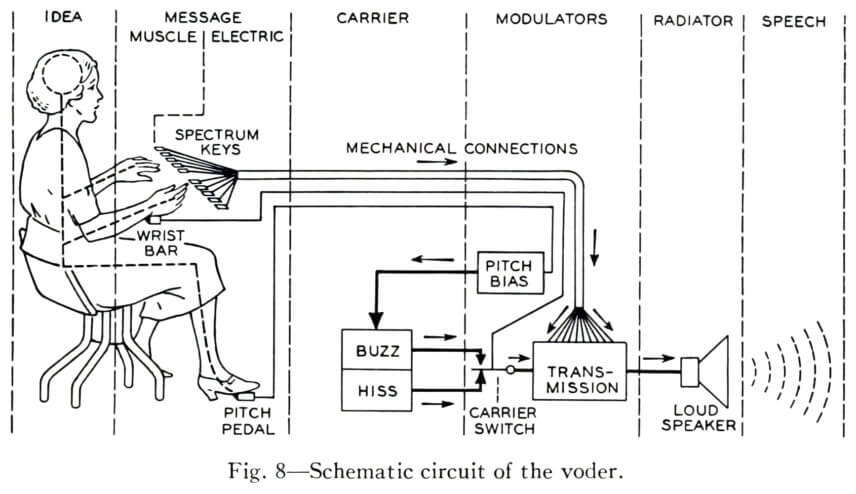

It was the Voder, however, that really got tongues wagging, as it were. Designed in 1937-1938 by Homer Dudley of Bell Telephone Laboratory (remember this name as we’ll be talking about him again soon), the Voder, or Voice Operating Demonstrator, was a machine that could electronically synthesize human speech. It was not automatic – it required a human operator manipulating keys and a pitch foot pedal – but it was remarkably intelligible.

As within many other sectors, speech synthesis improved significantly with the arrival of integrated circuits in the late 20th century. One of the first speech synthesis ICs was the Votrax chip, which used formants to mimic the human voice. It was at the heart of many computer speech synthesis programs and appeared in video games like Gorf and Wizard Of Wor. Texas Instruments’ Speak & Spell learning toy also benefitted from a speech synthesis chip.

Some early attempts at speech synthesis included singing as well as speaking. The Voder could also sing when played in the correct way. In 1961, an IBM 7094 mainframe computer sang ‘Daisy Bell’ (and inspired a famous scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey).

Speech synthesis development continues to this day. While many of the early attempts are charmingly primitive, modern speech synthesis – thanks to AI – is nearly indistinguishable from actual human speech.

Vocal Encoding: An Evolution, The Artists, And The Techniques

So now we return to Kraftwerk and ‘Autobahn’. While the German quartet was known to occasionally use speech synthesis (check out ‘Numbers’ for how to burn up the dance floor with a portable translation device), they’re most associated with vocoders. What could be more man/machine than singing through a synthesizer?

The vocoder has a fascinating history, stretching out into the past long before Kraftwerk asked a telephone company engineer to custom build them one. Wait, what does telecommunications have to do with the vocoder? Quite a lot, in fact. The vocoder (or voice encoder as it was originally known) was first developed in 1928 at Bell Telephone Laboratory by Homer Dudley, the same man who created the Voder. The vocoder was invented not as a way to spice up hot disco and electro jams but to make telecommunications easier. It was hoped that by splitting the voice into 10 frequency bands, the vocoder could transmit the parts through telephone wires using less bandwidth than full-frequency voice. With the help of a carrier signal (then just noise), it could put the voice back together at the other end of the line.

Unfortunately, the vocoder as designed by Dudley had no pitch information (remember, the carrier was just noise) so intelligibility became an issue. The idea was shelved until World War 2 when the Allied forces needed a way to secure trans-Atlantic conversations between Roosevelt and Churchill. Redubbed SIGSALY and with the help of one-time-use random noise records to act as unbreakable codes, Dudley’s vocoder was finally put to use. While vocoder telecommunications technology has continued to improve and in fact is still broadly in use in today, musical applications for the vocoder are a different story.

Musical vocoders function in much the same way as the old telecommunication version. The modulator (usually a human voice but not exclusively) is broken into a number of frequency bands. These are then combined with a carrier. While the original vocoder used noise and later filters to approximate formants at the carrier stage, musical vocoders replace them with synthesizers. The carrier can be a separate instrument or an oscillator housed within the vocoder itself. This way, pitch information can be applied, making the human voice appear to ‘sing’.

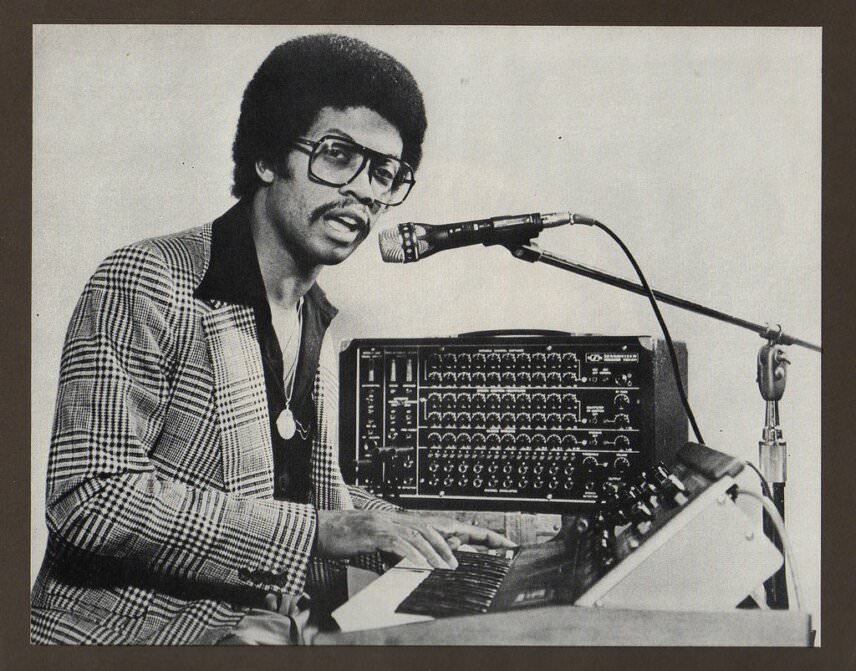

While there were a few nascent attempts at one-off vocoders, such as the Siemens Synthesizer in 1956 and the one built by Bob Moog for Wendy Carlos and used on the soundtrack for A Clockwork Orange, by the late ‘70s there were quite a few on the market, including the EMS Vocoder 2000, Sennheiser VSM-201, Moog 16 Channel Vocoder, Roland SVC-350 and VP-330, and the Korg VC-10. They were accompanied by an explosion in use in recorded music, first by artists like Giorgio Moroder and Electric Light Orchestra and later in R&B and electro. Vocoders were also employed as sound design tools for television shows, such as the voice of the Cylons in Battlestar Galactica, and in movies.

Vocoders continue to be popular in music production, thanks to Daft Punk and other artists keeping alive the traditions of classic dance music. Hardware vocoders – both dedicated and incorporated into otherwise traditional synthesizers – are also still being made, such as the Korg Minikorg, Arturia MicroFreak, and Behringer VP-340, which is a clone of the Roland VP-330.

Of course, modern vocoders are not restricted to the physical, with advancements in the software realm as well. One recent, powerful software vocoder is OVox from Waves. The instrument builds on the company’s previous Morphoder. It also adds quite a bit more functionality to the idea of the vocoder, improving on the basic design in a number of ways, with two synthesizer sections, harmonization, an arpeggiator, modulators and effects.

A few examples of the OVox in action.

In part two, we’ll continue our exploration into vocal synthesis with the history of the talk box and vocal pitch correction software.