Lack of accessibility is an issue that affects many music producers and DJs. We speak with three members of the disabled community to find out how accessibility impacts their creativity and performance.

We often think of accessibility in terms of access to physical spaces and services. Ramps for wheelchairs, elevators, audio cues for when it’s safe to cross the road. But accessibility applies to more than just buildings and public places. The presence (or lack!) of accessibility can impact music producers and DJs as well.

We spoke with three members of the music-making and performing community to find out how having accessible software and hardware directly affects their ability to do what they want to do. Note that answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Joey Stuckey – Shadow Sound Studio

Joey Stuckey was born sighted but became blind due to a brain tumour. “The doctors were very unsure that I would survive”, he says, “or if I did, they were pretty sure I wouldn’t walk or talk”. They were wrong, thankfully, and now he runs his own studio, Shadow Sound Studio in Macon, Georgia. He’s also active as a producer and session musician, among many other music-related things.

“I use as much analog gear as possible” he explains when asked about his music-making process. “This is for two reasons. First, I like that I can memorize the controls and they stay the same. Whereas with a screen-based, menu-driven system, controls are ‘soft’, meaning their function changes depending upon what screen you are on. This can be a real problem if you are blind and you don’t have access to that screen-driven information”.

Modern music production involves using computers, which necessitates working with screens. How does he navigate this? “I use several programs all with varying degrees of accessibility – Samplitude, Sound Forge, Reaper, and ProTools“, he says. “We have to use screen readers and there are three of note. JAWS and NDVA are both for PC and VoiceOver for Mac”.

His options are limited, though. There’s no one DAW or screen reader that provides full accessibility and third-party plugins can also be hit or miss. “iZotope, Native Instruments and Audified have all done some great work in (accessibility), but there is still much left to do.

I have also heard that Arturia has done some work with accessibility, but I haven’t used that personally. The problem is that it is hard to buy everything to discover how accessible it is or isn’t and even if you could afford it, it is very time-consuming. I dream of a day when the blind user has the same choices as the sighted user”.

I truly believe that most people would rally to this cause if they thought about the struggle.

Joey Stuckey

When asked how accessibility assists his creativity, Joey answers, “It doesn’t! It is just the basic function I need to get the job done and I don’t have full accessibility. I have to ask for sighted help when I can get it or farm out some things I can’t do to other folks. I want the same freedom and choice as my sighted counterparts and I just don’t have that.”

“The real problem is that our universe has become screen-driven and blind people have a very cumbersome way of trying to understand what is on the screen. We also can’t use a mouse or trackball at all and that is how most manufacturers imagine you using their product, so somehow we have to get around that obstacle”.

“First, we need to worry about accessibility for the future, not trying to retrofit a product already on the market”, he answers. “So, think about accessibility from the ground up as part of the framework from the get-go. Second, we need to have guidelines for best practices when thinking about accessibility in the digital market. Also, we need to adopt a common framework for plugin creation that is universal and that can be used by everyone so that each company doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel when thinking about how to make their product accessible.”

“And perhaps most importantly, we need to educate the greater music/audio community of the need for accessibility. Not only for blind or visually impaired folks, but for hearing impaired, or those with mobility issues. I truly believe that most people would rally to this cause if they thought about the struggle. I think that it just doesn’t cross most folks minds that there are those of us differently-abled that could make more meaningful contributions to the music/audio world but that just don’t have the access we need”.

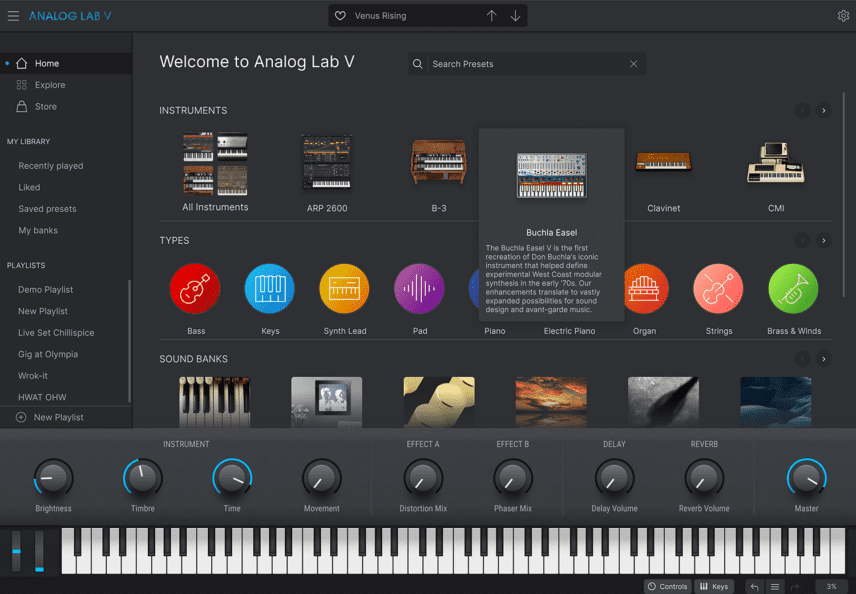

Pierre Pfister – Arturia

As Joey mentioned, one of the companies involved in accessibility is Arturia. As a result of working with blind producer Jason Dasent, the company has made its synthesizer plugin Analog Lab accessible to blind users when paired with a MIDI controller and a text to speech program. We spoke with Pierre Pfister, a product manager at Arturia, about the company’s commitment to accessibility.

The feedback we’ve had has been overwhelmingly positive

pierre pfister

When asked if the company plans to make more products available in the future, he answers yes. “The feedback we’ve had since this has been overwhelmingly positive. We are evaluating technical solutions to broaden accessibility to all our portfolio but we will do it step by step”.

They also plan to incorporate accessibility into their products going forward. “Designing new software with accessibility in mind is a challenge but it also forces you to make better interfaces for everyone, not only relying on beautiful graphics. For now, we are really at the beginning of our journey into accessibility. We are not experts by any means and will certainly face issues on the way, but I’m confident that the community is going to be a driving force to always go a step further”.

Kikarazu

Kikarazu is a Deaf techno and breaks DJ. (Deaf with a capital D refers to someone born without hearing, uses sign language and has a strong deaf identity.) He was raised in a home active in the arts, doing tap, ballet and contemporary dance, and also played the drums from a young age.

Stealing his sister’s Rage Against The Machine CD as well as being turned on to rave and drum and bass started him on the path to DJing. Actually finding a school that would teach him, a Deaf person, to DJ, however, was another story. London Sound Academy was that school, and, as he says, it completely changed his life.

As Kikarazu is Deaf, he can’t use headphones. Instead, he relies on a SubPac strapped to his chest via a custom harness to allow him to feel the music. “When SubPac was introduced to me”, he explains, “it was as if I had been asleep for most of my life. I use the lower SubPac area for the main beats and press my chin on top to feel more frequencies inside. I have invested so much time in learning how to communicate with the SubPac as it offers more frequencies than anything else I’ve ever found”.

Technically, his way of DJing is quite different from the traditional method. There are a lot of competing vibrations in a club to keep track of. “When DJing live, it becomes a maze. I have six different timings pushed onto me and it can be tricky to establish which one to follow: the sound system, reverberations on the booth’s floor, the needles on top of the Pioneer 2000NX2, the tiny (and annoying) ticking vibrations from the booth’s speakers, the SubPac standing in for a headset, and the dancers”.

Because of so much vibrational information coming his way, Kikarazu also uses his eyes to keep tracks in sync. “The world has become a lot easier since Pioneer’s Rekordbox introduced the 3 Band Waveform” he stresses. “This helps me view the music with my eyes and fit the pieces together like Legos”.

The main thing I can tell you is, the deaf community has been deprived of musical education.

Kikarazu

The resolution of the visual feedback, while helpful, could be better. “Our eyes are everything”, he explains. “Don’t get me wrong – Rekordbox is a miracle for people like me, but it has some flaws. When adding the tracks, the auto analysing is rubbish. However, it is the most deaf-accessible program I have come across, yet. This also affects the Sync button so I can never use it. Still, it keeps me on my toes and I have noticed that I enjoy DJing much more without it. So, learn from the Deaf DJ, folks: the Sync button sucks”.

Other frustrations include the inaccuracy of the LEDs on mixers, which makes it difficult to judge volume (“I tend to spend time analysing the volume of each track in order not to explode the ravers’ eardrums”) and the lack of volume consistency of AIFFs.

When asked what he would like manufacturers and the general public to know about the Deaf and hard of hearing communities, he says, “to be honest, I have never thought about it. I have been fixated on breaking the barriers that have been in front of me and adapting to them. But, the main thing I can tell you is, the Deaf community has been deprived of musical education. Please invest in us and you may find yourself another Beethoven or two”.

Steve Snooks – SubPac

For Kikarazu to be able to engage with the music, he uses SubPac, a device that vibrates in time to the bass of a track. “SubPac technology enables anyone regardless of their hearing ability to experience high fidelity physical sound”, explains Snooks, Head Of Partnerships and Sales at the company. “It’s a no-brainer to use a SubPac if you want to connect with sound and music especially if you are unable to experience audible sound”.

From my experience working with Deaf/Hoh individuals, charities and organisations, the major barriers tend to be related to education and costs.

Steve Snooks

When asked how music and DJ gear can be made more accessible for people who are Deaf and hard of hearing (Hoh), Snooks says, “I think it’s paramount we work with people from these communities and get them involved so we can navigate questions like this. We really need to listen and work with them firsthand”.

He also echoed Kikarazu, in that education and support is badly needed. “From my experience working with Deaf/Hoh individuals, charities and organisations, the major barriers tend to be related to education and cost”, he says. “There is plenty of amazing technology out there already and we need to make sure people are aware of it and enable them to actually gain access to it. The groundbreaking artists of the future are already out there; we just need to support them in finding the right instruments and tools!”.

SubPac, who will be releasing a new system early this year, originally designed the device for the broader music production community. “It just so happens to work amazingly well as a piece of accessible technology”, explains Snooks. “The Deaf and Hoh communities have really started to adopt it now and it really is amazing to see its use increasing”.

Bertolt Meyer

Bertolt Meyer is a modular synthesizer-based techno and house producer with releases on the DESSERT label. He was also born without his lower left arm and so wears a bionic hand, the i-Limb made by the Icelandic bionics company Össur.

Working with modular synthesizers presents a number of challenges as they have been designed for those with full mobility. “The potentiometers on the modules are really difficult to tweak with a bionic hand like mine” Bertolt explains. “The knobs convert a mechanical movement into an electric signal. My prosthesis converts a muscle signal from my residual limb into an electric signal, which is then converted into a mechanical movement of the hand, which I then try to use to create an electric signal. I thought that was stupid – too many adapters, if you like”.

His solution was the SynLimb, a hack for his prosthesis that he developed with Christian Zollner from KOMA Elektronik and his husband, Daniel Theiler. It attaches directly to the socket of the prosthesis instead of the bionic hand and converts EMG muscle signals into control voltage for use with the modular synths. “Basically, the SynLimb has two outputs that I can directly connect to any CV input like a filter cutoff or the pitch of an oscillator”.

Because it’s connected to his body, working with the SynLimb is effortless for Bertolt. “For me, creating these CV signals just feels like thinking about opening or closing my hand”, he says. “In this way, for me, it feels as if I control the synth with my thoughts when I play it with the SynLimb”.

When asked about how his creativity and efficiency have changed thanks to his SynLimb, Bertolt responds, “I used to feel quite limited when playing the modular in comparison to my two-handed colleagues. Now I feel that I can do some things even quicker than they can”.

I wish that the industry understood that making accessible controllers more mainstream is a potential benefit for everyone.

Bertolt Meyer

When asked what he would like manufacturers and the general public to know about the disabled music-making community, he replies, “I wish that the industry understood that making accessible controllers more mainstream is a potential benefit for everyone, not just for the niche market for musicians with special needs. For example, a MIDI controller based on motion sensors, like the SOMI-1 by Instruments of Things, is interesting both for musicians with and without special needs”.

Bertolt is working on a second version of the SynLimb with more security and a connector for a Bluetooth module. Once it is ready, he plans to release it as a DIY open source project.