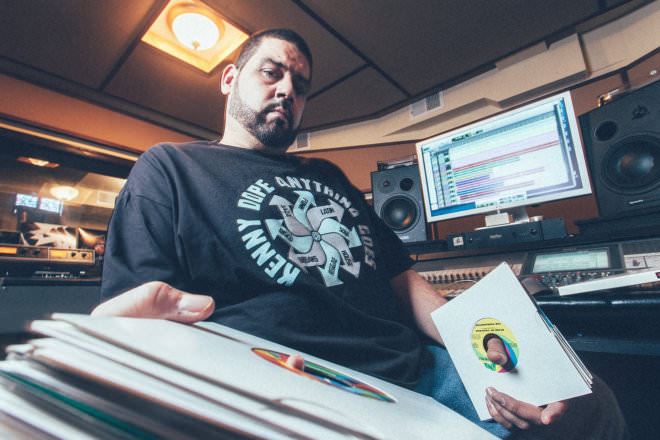

Attack editor Greg Scarth talks to one of the most revered producers in house as he relaunches his Dopewax imprint.

After three decades in the music industry, Kenny Dope still has plenty to say. In conversation, he’s just as likely to talk enthusiastically about the latest advances in software and studio technology as he is to reminisce about the good old days starting out as a kid in Brooklyn in the 80s.

We called him to discuss the evolution of his production techniques, why he usually turns to plugin emulations rather than pulling out the original synths from his vast hardware collection and why working with the younger generation has reignited the “fire” that motivates him to make music.

Photos: 101 Apparel

Attack: Let’s start with the present day and work our way back. Tell me where you are right now with your music and the Dopewax relaunch.

Kenny Dope: Yeah, well it’s been 27 years since the first record of Dopewax. It was made to put my own stuff out whenever I wanted to, and style-wise whatever I wanted to, so at the present day I’m really digging stuff that the younger generation are doing so I thought why not collaborate with those artists and DJs on some music. Since I’m digging them and they respect me for what I’ve done, I think it’s a beautiful thing to bridge the gap and come together to work on some new stuff.

A lot of the guys that came up at the same time as me or came up before me are not really embracing that generation, but what they don’t remember is that we were that age one time. We were naive, we didn’t know, we were learning the craft. I just feel like I learn something every day, whether it’s life stuff, music that I’ve never heard before or production tricks, I’m constantly learning, so why not work together? I’m also doing my own stuff, but I’m toying with doing a whole album of collaborations. I haven’t really decided.

we put out records and things would just appear in record stores... if they find it, they find it; if they don’t, they don’t. Now I just kind of wanna let people know that this music is there.

OK, cool.

At the same time, the promotion’s got to be in place. You’ve got to realise that over the span of those years, we put out records and things would just appear in record stores. When the internet got involved we just did things the same way: if they find it, they find it; if they don’t, they don’t. Now I just kind of wanna let people know that this music is there. The old stuff as well as the new stuff that’s coming.

So it’s a different game now compared to what it was?

Yeah. At the end of the day it’s been so long that I’ve been doing this that I just want to let them know it’s there. As a DJ, I’ve been playing to younger audiences too, so for me it’s like I’m reintroducing myself to them. Or introducing myself to them. I’m not going to sit here and tell you that everybody knows who I am. I can’t even say that. Somebody who’s 19 or 20 might have never even heard of me, and if they did they heard it from a brother or a mother or a father who played my music.

That’s a great thing. DJs now are still dropping your classic tunes and kids aren’t hearing those tracks as oldies. It fits in the context of what’s going on today. What do you think is the biggest difference if you compare being involved in music today to back in, say, the mid 90s?

The technology has changed drastically. Things that used to take me two or three days to do, I could probably do now in a day or less. We’re also able to collaborate easily. If a kid’s in Germany or London or France or wherever, I can send him some tracks, he can work on it in his studio, send me some files, talk on Skype. Back in the days when you worked with someone you had to be in the studio together or send them the reel of tape for them to work on it. The only thing I miss in a collaboration is interacting with whoever you’re working with.

Face to face, yeah.

So basically what I’ve been doing is if anyone’s coming to New York we book a session. I just did a session with wAFF this week and that went really well. I’m in the studio with Oliver Dollar Monday and Tuesday. That’s how we’re approaching it.

So it’s a lot easier for you to make music these days.

The stuff is easier to make today, but it’s that much harder to get it to the world today. You gotta realise that I could put out a record in the 90s, press 3,000 copies and then the following week get an order for 15,000 more. And then the following week get another order for 20,000 or 30,000 more. Those records would reach places we would never even think of – the only time we knew is when we started getting our royalty cheques and it was in countries that you couldn’t even pronounce.

Today we’re able to reach so many more people but it’s that much harder because everybody’s doing music, everybody has a computer, everybody has a SoundCloud account. It’s saturated. If you go to Traxsource, Beatport or whatever, there’s so many records coming out. That doesn’t mean that they’re all good, it’s just flooded. That’s a good thing but it’s also a bad thing. I love the fact that everyone wants to control their stuff and put stuff out on their label, but there’s no filter. I’m not mad at it at all because I was that age once. I don’t knock anyone trying to get their music out there and going for theirs.

Were there positive aspects back in the 90s that people maybe wouldn’t know about today?

The thing that was good back in the days was the friendly competition. You had Chicago with their sound, you had Detroit with their sound, you had us in New York with our sound. We heard each other’s records and got influences back and forth and it was that kind of flavour. I – with Louie, separately, together, whatever – we just wanted to keep incorporating different aspects of musicianship to the music. We were bringing all these different flavours of music, and the crazy thing is a lot of that stuff was before its time. We were just creating, every day. I didn’t realise the amount of stuff and the abundance of music that we created until probably 2002. From ’90, it was on automatic pilot, just going and going and going.

I didn’t realise the amount of stuff and the abundance of music that we created. It was on automatic pilot, just going and going and going.

It’s all good today though. Like I was saying before, the thing about technology is that it’s all moving and you have to adapt to it, you have to embrace it, you have to study it. Things were very different when you made a record analogue compared with making a record digitally. With digital you fight with frequencies and you fight with sounds.

But on the other side of it, in my studio I may have seven or eight keyboards that are worth seven, eight, nine thousand dollars a piece. Meanwhile, I can buy a plugin with ten of those pieces for three hundred dollars, and the sound is just as good if not better, with more features. There’s a lot of pros and cons to being in the business today.

If you look back at the studios you were producing in back in the 90s, it was an expensive world. Like the Nuyorican Soul album, those were big budget studios But even if you weren’t at that top level it was expensive to get into.

Absolutely. You’ve gotta realise that my first pieces of equipment probably cost $7,000. Two pieces of equipment, the Akai S950 and the SP-1200 drum machine. I didn’t even purchase them, they were bought for me by the label, you know?

People look back at it as a golden age, but there were definitely some downsides there.

A record could take you a day to make or it could take you five days. I remember when we were doing remixes, to time-stretching a vocal could take you three days. Now I could stick that in Melodyne and do that shit in an hour. But I wouldn’t take that experience away for anything in the world, because now I can work really fast. Back to what you were saying about the keyboards, my whole thing was I wanted every sound possible that was ever recorded on a piece of vinyl.

I wanted every sound possible that was ever recorded on a piece of vinyl.... Next thing you know I have 82 keyboards.

Right.

So I did my homework for years and years and years. I’m a big record collector, so I would read on the jackets like who was playing what.

Yeah, that was a big thing back in the 70s, wasn’t it? If you look at things like Herbie Hancock records they list every single keyboard he used.

Yeah, you know, if it was a Headhunters record or whatever. George Duke or whatever. If they were playing these synthesisers and I liked that sound, then I would go and find that keyboard. You know what I’m saying? I wanted the original sound because I wanted to incorporate that in what I was doing. Next thing you know I have 82 keyboards.

Wow.

[Laughing] You see what I’m saying? It’s crazy. But, like I was telling Waff the other day, it’s like: ‘Look, don’t get it twisted. Everything I have in this room, I have as a plugin. We can go hardware – it’ll take a little longer but it’s gonna sound different – or we can go plugin, and we have the same textures but we can work faster.’ You see what I’m saying?

Definitely. That’s a good decision to be able to make, though. How do you feel about the fact that so many young producers are getting into the old hardware-based workflows over the last few years?

It’s crazy. I always said that things travel in a circle. There’s a certain point in life where you were there and it revolves and revolves and then you’re back there again. It’s crazy to see how everything’s moving to hardware again; Akai’s got a new hardware MPC coming out, Roland just did the 808 and the 303 and the little toy version of the Juno. It’s great that the younger generation get to experience that feel.

Do companies ever ask you to give your input on product development.

All

day.

Do you get involved?

Yeah! I was just with Pioneer two days ago. I’m friends with Roland, friends with Ableton, friends with Native Instruments, you know? It’s great.

There’s a rumour that there’s going to be some kind of reboot of the SP-1200, which I know is something you’ve used a lot in the past.

Really?

It’s just rumours at this stage.

Wow. That’s amazing. That machine was ahead of its time. I abused it – I know it inside out. The thing is that it made you work, because you only had limited time, so it made you be creative. It had a certain sound but also it was very easy to use. The whole manual is on the face of the machine. I always tried to explain to these manufacturers, make this shit simple. If you could put in all the features but make it simple, these kids – or us

– will be able to grab the machine and just use it and not have to sit for weeks and weeks figuring out where things are or that you gotta hit three keys for one function.

The SP-1200 was gritty. It was used in both hip-hop and in house. Actually, there are some companies still today that’ll expand your memory, add features so you can monitor the input, and so on and so forth. I was thinking of doing it to one of my machines, because I have three of them.

you’ve gotta realise that in dance music a lot of this stuff was trial and error. You’re pushing buttons, testing the waters. A lot of this stuff, it’s so perfect, but it’s not a perfect world in dance music, you know what I mean?

Do you still use them regularly?

Um, not regularly, but I still use hardware pieces whenever I feel like getting that sound again, because there’s nothing like it. They’ve tried to make plugins to emulate it, but it’s nothing like the original.

I think most sampler emulations are still a long way off. There’s a rumour Roland will be releasing a new AIRA sampler too.

I think with Roland stuff – and I’ve told them this before – with their samplers, they cover a lot of space and they sound incredible, they’re just difficult to use. Like with that MV-whatever-it-was, that grey drum machine, everything was on it. It was just difficult, man. I told them just put those features on it but dumb it down a little bit – it should be easier and faster to use. I said you’ve gotta realise that in dance music a lot of this stuff was trial and error. You’re pushing buttons, testing the waters. A lot of this stuff, it’s so perfect, but it’s not a perfect world in dance music, you know what I mean?

Roland have developed a much better understanding of dance music over the last couple of years.

The biggest thing is that the actual founder and owner [Ikutaro Kakehashi] resigned. He was really a hardware dude, he didn’t wanna embrace plugins, so when he resigned and the younger guys were able to take a hold of the company that’s when everything started to happen. It’s like, think about it: every company has Roland’s sounds in their stuff. If they were to capitalise on their stuff so long ago it would have been so crazy.

It’s like they didn’t realise…

Oh no! He realised. He just didn’t wanna fuck with it!

Speaking of samplers, I’ve heard people say you made ‘The Bomb’ on an SP1200, I’ve heard people say you did it all on an MPC. Which was it?

Nah, ‘The Bomb’ was done on an SP and an S950. The way I used to do my beats back then, all my rhythms and my drums were in the SP, but it didn’t hold long samples so all the long samples were in the S950 and I would trigger them from the drum machine. That’s how that record was made – and how a lot of records were made in that time period.

I guess that was pretty common in New York house and hip-hop at the time. I think people like Pete Rock and Q-Tip were using the same combination.

Absolutely. And there was a certain vibe to the two as well. Even today you can have unlimited amounts of sample time in a machine, but it’s a different vibe to those two machines.

So did you move on from the SP to MPCs?

I have everything. Before the SP1200 I used a drum machine called the RZ-1. It was a Casio.

I have one of them. They’re really good fun.

I used that because it’s what we could afford, but then when they bought me those two pieces [the SP1200 and S950], I used that for a long time. I never really used the MPC60 at all – I was never a 60 fan – but then when the 3000 came out there was a period where I was using both machines at one time, [the 3000 and SP1200] synced together. Then I got the 2000 and the 2500, I used the 5000 for a period and now I use the Renaissance or Maschine. Like I said, I go back to the 5000 and the 3000 and the 1200 whenever I want that feel, because there’s nothing like it. The converters in the 3000 are just knocking.

You can actually tell the difference in the foundation of the beats when I started using the MPC. It opened things up and gave everything a very analogue-y, fat sound.

The 3000’s got that classic sound that’s mostly associated with hip-hop but it was used a lot in house too.

Yeah, yeah. I used it a lot too. You can actually tell the difference in the foundation of the beats when I started using it. We’re talking about ’97, ’98, ’99, 2000. It opened things up and gave everything a very analogue-y, fat sound.

What were you using when you made ’The Nervous Track’? Was that on an MPC?

‘The Nervous Track’ was ’95. That was done with the 1200 too, actually.

Wow. You must have been pushing the SP pretty hard, with the loops on that.

The crazy thing is that you had only a certain amount of time, so I had to sample those loops at 45 and bring them in and pitch it down. What that did was it created this noise in the loop, but it was actually good, you know? The roughness, the scratchiness of it, gave it a vibe too.

Most definitely. We just did a feature on how to recreate that kind of effect on the little Korg Volca Sample.

Oh really? I never used it, actually. I was at Korg maybe about a month ago. They were showing me the Odyssey but I saw those little ones and I was like, ‘Woah, that’s crazy’. You know what else is really cool? For people that work on the fly, the Korg Gadget is pretty hot. Again, it’s a different way of working. I don’t love doing beats on the iPad screen, but to get ideas down it’s really cool.

Do you work a lot on the road?

All the time. The record I just put out with Robert Owens, ‘Bricks Down’, was sketched on Gadget on the iPad. Like I said, you use what you have at the time. When you have an idea, a bassline part, a drum part – whatever’s at your disposal, that’s what you use. That’s where I come from. Whatever you have, you make do with what you have. When you’re poor and you can’t afford it or whatever, you do with what you have. That’s always stayed with me. I can use anything to get my idea across.

It only just struck me recently how bold it was that you called yourself Masters At Work when you were just teenagers. That was when you were starting out DJing, right?

That was my crew’s name initially. It was me, Mike Delgado and Franklin Martinez, three kids in Brooklyn who wanted to create. Franklin used to do these tape edits on reel-to-reels that were just amazing. Then there was my background in hip-hop and reggae and disco and house and all that stuff, and Mike was just a little older than me and he was going to the Garage and that kind of stuff. We started doing parties and getting the brand out there but then Franklin moved away and Mike had a baby. I was like, ‘Look man, I really wanna pursue this.’ I was like 17 years old. At that same time period that’s when I met Todd Terry. He was putting out records so that’s when I lent him the name. I was like, ‘Look man, I’m gonna need that one day.’ Next thing you know, two or three years later, I’m like, ‘Yo, I need my shit back.’ I need my name because I wanna create some things. That was the origin of the name.

Masters At Work, though. That’s a bold claim to be making when you’re a little teenage crew, you know?

Exactly, but…

Not to mention the fact you were calling yourself Dope!

I’ll explain that in a second. Masters At Work was because we were masters in our neighbourhood. Nobody could mess with us musically, nobody could mess with us DJing, nobody could mess with Franklin on the edits. That was the whole concept of that, way before any of this other stuff.

With the Dope name, that came from Todd. I was at his studio one day and I said, ‘Oh, that’s dope.’ Next thing you know he’s introducing me to everyone as Kenny Dope and I’m like, ‘What are you doing?’ Ever since that night that shit stuck and I was tagged with it.

I was at Todd Terry's studio one day and I said, ‘Oh, that’s dope.’ Next thing you know he’s introducing me to everyone as Kenny Dope and I’m like, ‘What are you doing?’ Ever since that night that shit stuck and I was tagged with it.

If you’ve got a big name you’ve got to live up to it.

Exactly. I’m just into what I’m doing. I study my craft and everything that I’ve ever done is 110%, so it kind of lives up to those two names. I never did things half-assed. If I didn’t like something, I wouldn’t do it, no matter how much money was on the table. If I don’t like it, I’m not doing it. The same thing goes for the amount of records we came out with. There’s probably double or triple the amount of music that didn’t come out because we didn’t like it enough. And the same for offers and remixes that we turned down because there was nothing in the record to inspire us. It wasn’t about the money at all. That’s what makes the longevity crazy.

You mentioned how prolific you realised you were. Are you still as prolific, working at the same kind of speed?

Nahhhh. I feel like I’m at 60% now. You gotta realise things are different than when I was 20 and 30 years old. I was going out, experiencing a lot of different things. Now I’m a lot more laid back than what I was. I have a family now, I just had triplets a year and a half ago. Things are different. Your responsibilities change. I’m 45 now, I’m in a different place. It takes me longer to get back in a rhythm when I get back home from travelling.

It’s cool to hear that you still sound motivated and enthusiastic about music either way.

Man, there’s nothing like it. I’m not gonna say that I haven’t been through periods where you get disappointed or you get down on where things are going – I’m human and I’ve been there – but when you hear some kid doing some crazy shit it inspires you all over again. There’s a lot to conquer. I’m feeling that fire again, that competitiveness of wanting to do better than the next man or whatever. It goes hand in hand, you know?

Kenny Dope and Robert Owens’ ‘Bricks Down’ is out now on Dopewax. Find Kenny on Facebook, Twitter and SoundCloud.

03.31 AM

This was a “dope” article! 🙂 No for real thank you ATTACK again! Kenny Dope is one of my favorites. Right along side Little Louie and Todd Terry!

02.03 AM

Absolutely incredible interview. I’m not even the biggest MAW/NY house fan, but every time I’ve read Any MAW interview, it’s just full of golden nuggets. Two men for whom the title ‘legend’ is actually appropriate.

02.04 AM

Great article Attack. Also, everybody should check out the MAW RA exchange audio interview – it’s one of the most inspiring music interviews I’ve ever heard – real head shit! 😉