We pay tribute to the forward-thinking Black techno and house artists who discovered new ways to use their gear and changed the way we hear dance music in the process.

Pretty much all of the genres of music that we love were invented by Black artists and musicians. From house and techno to drum and bass and garage, reggae to jazz, funk to the blues, and with few exceptions, the music that drives us, that soundtracks our very lives, came from within Black communities. While this is widely known, what is less appreciated is how the very way that we use our instruments and gear to make music is largely influenced by Black artists.

Whether by pushing a piece of gear to its technical limits or discovering entirely new ways to play it beyond any intention of the manufacturer, a handful of trailblazing Black musicians has shaped the way that we hear and make modern music. The drum machines we rely on, the synths we regularly utilize, even the very way we DJ—these all owe a debt to Black originators.

It’s long past due to pay tribute to the ways in which Black artists revolutionized the way we hear music. Of course, this legacy extends beyond the boundaries of dance music (Jimi Hendrix, Miles Davis, Roger Troutman, Bernie Worrell—the list is endless) but here we’ll be focusing primarily on the dance music luminaries that blazed the trails that we all now follow.

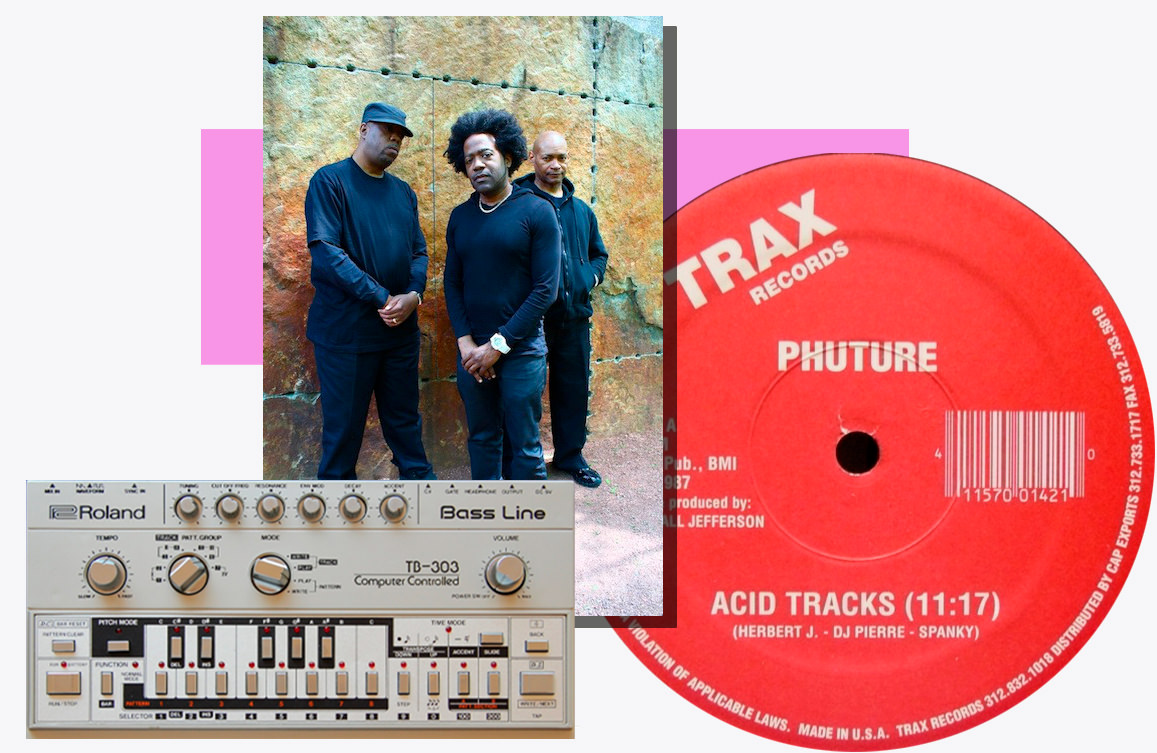

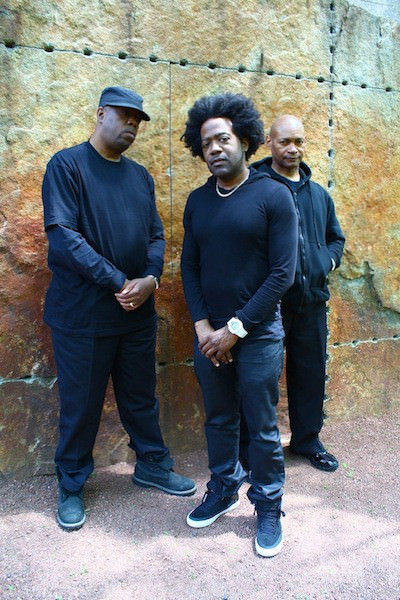

Phuture

Roland TB-303

The story is well-known but it deserves to be told again. Roland released the TB-303 in 1982 in tandem with the TR-606 drum machine. It was meant to help guitarists practice by taking the place of a bass player. While it did make its way onto a few records of the day like Shannon’s freestyle hit ‘Let The Music Play‘, the fact that it was extremely hard to program and sounded absolutely nothing like a real bass ensured that it was soon to vanish from music store shelves.

Enter Phuture who recorded themselves messing around with a newly acquired second-hand unit on top of a drum machine beat. They liked the way it sounded and took it down to Chicago proto-house club the Music Box, where Ron Hardy played it four times in one night. While it reportedly cleared the dancefloor the first time, by the fourth people were losing their minds. With that song, called ‘Acid Trax‘, acid house was born.

What set ‘Acid Trax’ apart from other records that had been made with the 303 was the way in which it pointedly ignored the purpose of the machine. The constant tweaking of the filter and other settings transformed it from a terrible bass guitar into a science fiction monster. It put the focus on the freaky. No one would even think of using a 303 now as a static bassline generator. It begs to be tweaked, and that’s all down to the pioneering programming of Phuture.

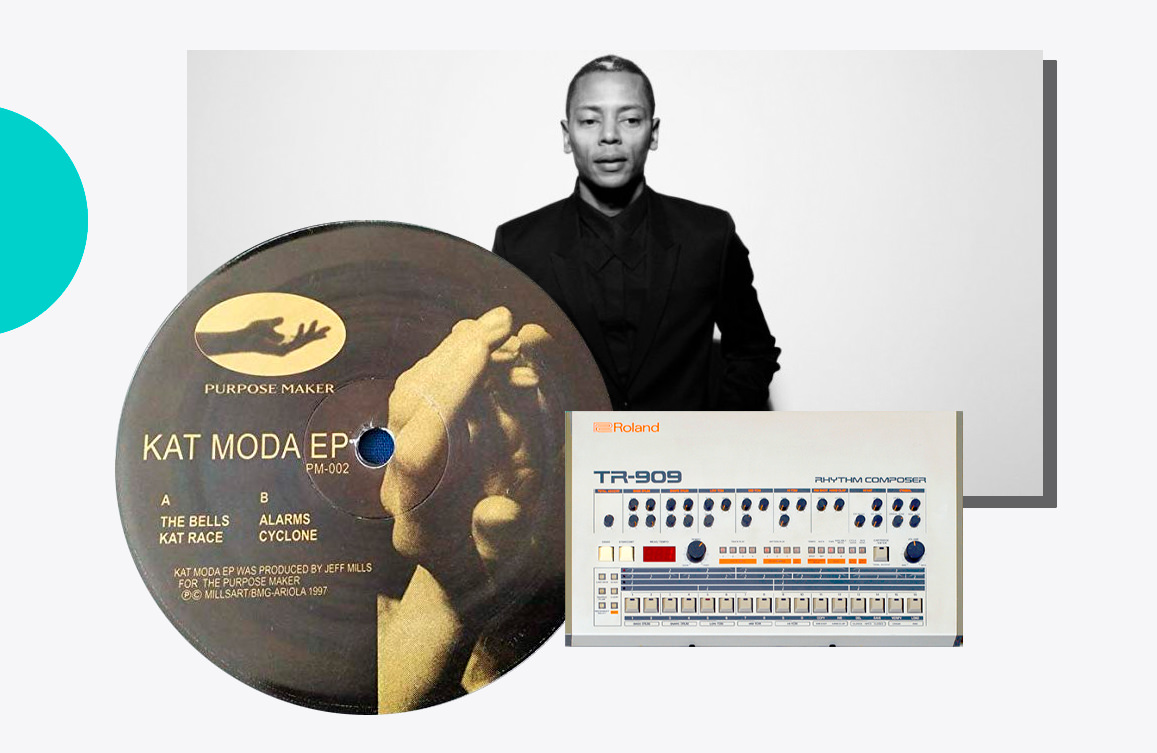

Jeff Mills

Roland TR-909

Roland’s other famous drum machine, the TR-909, was released in 1983. Much like the TR-808, it was not a big success at the time and, despite having some sampled sounds to augment its analogue-synthesis-based circuits, customers largely preferred the LinnDrum and other sample-based drum machines. Ask any Attack reader who is synonymous with the TR-909 and likely no one will say Phil Collins. While it was used by the ’80s pop star in ‘Take Me Home‘, the 909 didn’t really achieve any kind of wider popularity until dance music producers, attracted to its heavy kick and punchy sound, started to take to it in the late ‘80s.

One of those producers was Jeff Mills of Underground Resistance. While not the first to work a 909, he has arguably done more to influence the way techno producers program and produce the 909 than any other. First with UR and then later solo, Mills put the 909 front and center in the mix and relied on it to carry the track with thudding kicks, incessant hats, and ringing rides.

In an interview, Mills stated, “I don’t have any secrets, but the way that the 909 was made makes it possible to really play the machine, not just program it”. As a drummer himself, Mills used the 909 as a drummer would, tweaking the tuning of individual percussive elements to create tiny variations in sound. Techno owes a great debt to Mills’ masterful use of the 909 on ‘The Bells‘ and across his extensive and influential discography.

Kevin Saunderson

Casio CZ-5000

The Reese bass sound has become a dance music staple, popular not only in drum and bass but across many genres of bass music. The sound was originally created by Detroit pioneer and one of the Bellevue Three, Kevin Saunderson. Developed for the song ‘Just Want Another Chance‘ and released under the pseudonym Reese (hence the name of the patch), the sound was reportedly cooked up to sound like something dark that Larry Levan of the Paradise Garage might play.

Coaxed out of a Casio CZ-5000 (1985), the rumbling bass sound was first sampled by drum and bass producers in the 1990s and then further expanded upon. A modern Reese, with its tearing high-end and twisting low end, hardly resembles the original anymore. But that’s beside the point. Saunderson’s Reese sound may not have been the first “dark” synth bass ever recorded but it certainly paved the way for darker sound design in music.

Derrick May

Yamaha DX100

If classic Chicago house was made largely with cast-off Roland gear, then the first wave of Detroit techno relied heavily on FM synthesis. It was hard, uncompromising, and almost alien-sounding, perfect for the kind of forward-thinking music coming out of the city. Perhaps the most popular synth in Detroit in the late ‘80s was the Yamaha DX100 (1985), prized as much for its gritty tones as for its affordability.

No one made the DX100 their own like Derrick May, who used it on a number of his classic tunes. ‘Nude Photo‘, released under his Rhythim Is Rhythim alias, is built around the Wood Piano preset and ‘The Dance‘ leans on the DX100 heavily as well. With only four operators (compared to the DX7’s six), the DX100 as used by May tended towards the harsh and brutal—a perfect reflection of the urban decay techno was born in.

In a 1990 interview, May said that his DX100 had been modified with an Oberheim Matrix 12 filter circuit, which gave it a kind of extra edge, making it sound “harder than before”. Even then, May was pushing his sound to the extremes. Thanks to May and the other techno pioneers, techno is still minimal, hard and uncompromising.

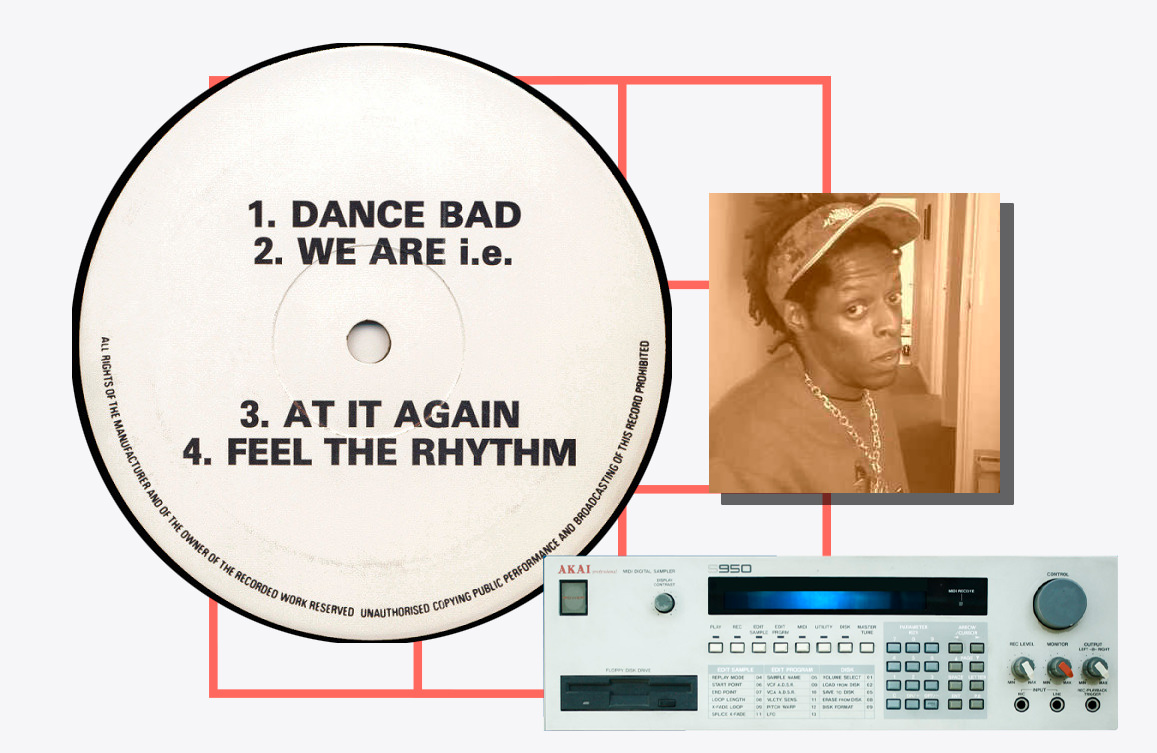

Lennie Dee Ice

Akai S-950

Speaking of uncompromising, let’s talk hardcore. Sampling funk breaks was nothing new in the late ‘80s. It had been popularised by hip-hop artists who saw it as a natural progression from DJing to production. But it was Lennie De Ice who helped usher in a new style of music in the UK by combining heavy dub bass with an Amen break chopped up in an Akai S-950 sampler.

Originally made in 1989 but not released until 1991, Lennie De Ice’s ‘We Are IE‘ was a watershed moment for UK bass music, setting the stage for both hardcore and what it would later mutate into, namely drum and bass. It was the S-950 (1988) that made everything possible, with sampled gunshots, ethnic vocals, and of course the unstoppable Amen.

Akai would go on to release a bewildering number of machines in the S series, but it was the S-950 that first featured time stretching. This allowed producers to change speed while still maintaining pitch, something that would become more and more important as tempos increased. It all started with ‘We Are IE’ and thanks to De Ice’s forward-thinking use of the sampler and the Amen break, UK bass music would never be the same.

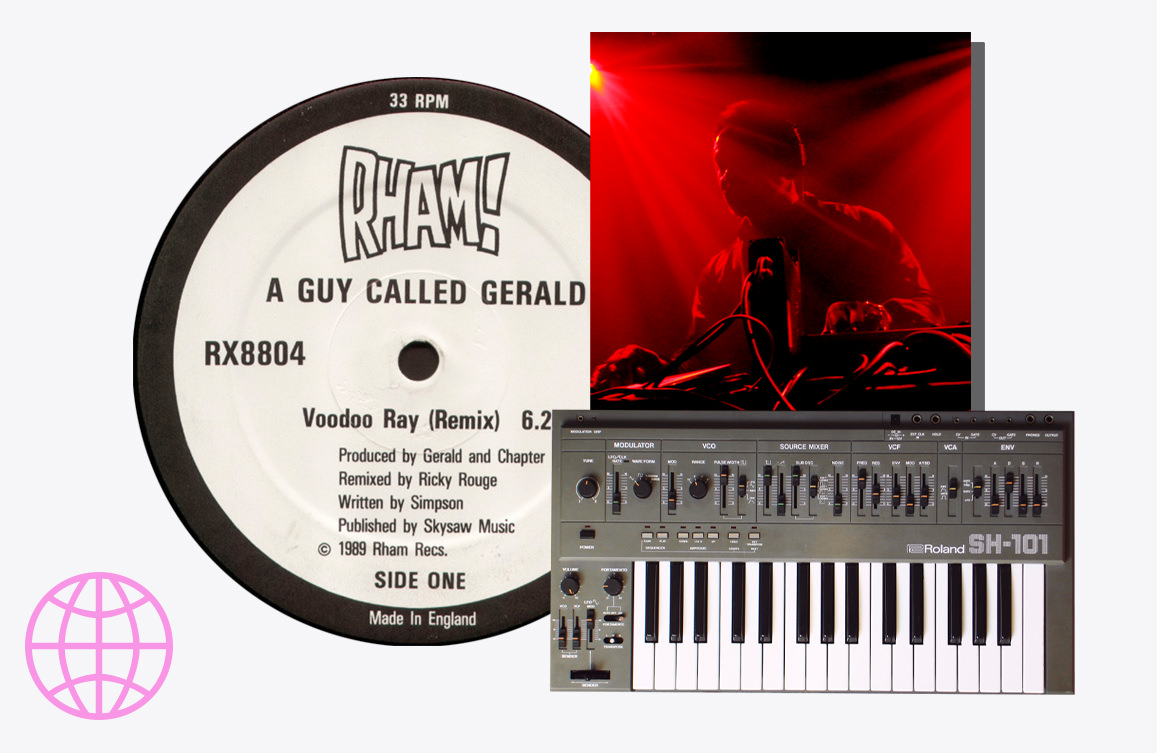

A Guy Called Gerald

Roland SH-101

A Guy Called Gerald may be best known for his acid house classic ‘Voodoo Ray‘, but it was his work with the Roland SH-101, first released in 1982, that helped make a lasting association between the monophonic synth and techno. ‘Voodoo Ray’ benefitted from the not insignificant bass contributions of the SH-101, helping it stand out from other club tracks of the day.

A Guy Called Gerald didn’t play the SH-101 so much as program it, triggering it from his TR-808 and letting it snake alongside the 303. You can hear this on the 808 State album Newbuild, especially on ‘Flow Coma‘, where he wielded the SH-101 like a second 303. He also occasionally used two units in tandem to push new harmonics out of the single-oscillator synth.

These days SH-101s sell for ridiculous money, with plenty of clones also on the market hoping to tempt punters away from their cash. The reason that the SH-101 is so sought after today is thanks to the work of early techno and house producers like A Guy Called Gerald.

Afrika Bambaataa

Roland TR-808

Roland’s now ubiquitous TR-808 drum machine was released in 1980. Despite new wave and synth pop being all the rage at the time, the very electronic-sounding TR-808 didn’t fare so well against other drum machines like the Linn LM-1, which used samples of acoustic drums. While it did appear on a few pop hits, notably ‘Sexual Healing‘ by Marvin Gaye in 1982, it wasAfrika Bambaataa’s visionary use of the machine on ‘Planet Rock‘ the same year that showed the world what it could do.

Bambaataa, who in recent years has denied allegations of historic sexual abuse, pioneered the use of the TR-808 in dance music. Essentially Kraftwerk’s ‘Numbers‘ reprogrammed, the ‘Planet Rock’ rhythm track is electro 101: snappy snares, cold, insistent hats, pulsating cowbells, and that kick, a subsonic boom that shakes the walls like an electronic earthquake. Before ‘Planet Rock’ nothing really hit so low. It added an unheard-of amount of speaker-blowing bass to records.

Working with producer Arthur Baker and musician John Robie, Afrika Bambaataa harnessed that low end and used it to underpin ‘Planet Rock’. It birthed electro, of course, but most bass musics in general. It ushered dance music into an era where the low end was increasingly more important, an era that we are still in now.

Todd Terry

E-mu SP-1200

The E-mu SP-1200 (1987), has a long history in hip-hop. But, like the Akai MPC series, there are plenty of house producers who use them too, and one of the best known is Todd Terry.

Terry got his start in hip-hop and brought those production techniques to house, layering sampled one-shot drums (often from the TR-909) with hip-hop style breaks. His beat programming is immediately recognisable, the layering of percussion manic and infectious.

When asked in an interview why he liked the SP-1200 so much, he replied, “It has a raw house sound”. This rawness comes from the 12-bit resolution and 26.04 kHz sampling rate, which restricts the highs and makes everything sound warm. Todd Terry certainly used this to his advantage, squeezing the best out of his grey box and bringing a hip-hop production style to the world of house music.

Frankie Knuckles

DJ Gear

For this last entry, we’re going to focus not on the specific gear used but how it was used. Frankie Knuckles was the resident DJ at the Warehouse in Chicago from 1977 to 1982, and then at his own club, The Power Plant, from 1982 to 1987. At the Warehouse, his record selection—disco numbers, Philly soul, and later electronic European records—became known as warehouse music, eventually shortened to just house music.

As the ‘70s ended and the steady stream of American disco records dried up, Knuckles took to making his own edits, playing his radically reimagined cuts on reel to reel units. At the Power Plant, he started experimenting with using drum machines in his sets as well, layering them under the records, and in 1984 even bought a Roland TR-909 from a young Derrick May, who would make the drive down from Detroit to hear Knuckles play.

Knuckles was not the only DJ at the time making his own disco edits and layering drum machines under records but because of his track selection, his reach, and his talent, his epic, 12-hour DJ sets in these ten years laid the foundation for what would become the global phenomenon that is house music.

A Statement From Attack Magazine

At Attack Magazine, we recognise that the music and culture we love comes from the black, brown and LGBTQ communities of America.

We stand in solidarity with everyone protesting for equal rights, in America, here in the UK and across the world. We recognise that the current protests are taking place in the context of centuries of social and economic deprivation that has been endured by black people.

As committed anti-racists, we stand in solidarity with all those across the world who feel anger and fear at continued discriminatory state violence. It is also crucial that we recognise UK music is not immune from institutional racism, and that systemic racism exists in club culture.

Real structural change will not happen overnight, but we are aware that here at Attack we have a part to play in addressing our own subconscious bias and ensuring that we speak to, and about, all people in our coverage of club culture. We are strongly committed to playing our part in making the world a more just and equal place.

Black Lives Matter.