Greg Scarth talks to pianist Leon Michener about his unique sound, which fuses techno and electro influences with modern classical composition and performance techniques.

London label, club night and musical collective Nonclassical, led by composer Gabriel Prokofiev, has been exploring the intersection of club culture and modern classical music since 2004. Ahead of Rise Of The Machines, an ‘orchestral club night’ to be held tomorrow night at Ambika P3, west London, Nonclassical’s Klavikon – aka Leon Michener – explains why he’s not comfortable with the term ‘piano techno’ and how he creates a kick drum sound using “a lot of Blu-Tack and a ruler”.

Let’s start at the beginning: how did you fall into creating piano techno?

‘Piano techno’ is not a term I have ever used, or feel comfortable with – it was coined by a promoter. It’s understandable – they need to sell tickets and find a hook.

OK, so how do you describe your music? I’ve seen it described as ‘reimagining’ electronic music or attempting to imitate electronic sounds with the piano – how do you see it?

Neither of those. I simply make electronic or electro-acoustic music with the piano as a workstation, ‘sequenced’ by my fingers. I’m not trying to imitate, but unearth new sonorities that are hidden beneath the clean uniform grid of black and white keys, locked deep in this complex machine. I’d like to see it as the evolution of the traditional solo piano recital, demonstrating that with a few simple modifications it can put out a sound as loud and deep as any modern electronic or rock group. Like any musician, I reference and pay my dues to the styles and sounds that have influenced me through my life.

I decided to find a way to combine what I always wanted to do: electronic music production and playing. I ditched the computer and dumped a mic and speaker inside the piano and went from there.

Did you come from a background of classical music or experimental music?

Neither. I got hold of my first analogue synth as a kid in the 80s, then a Boss DR-110, and made tracks by dubbing two cassette tapes together. At that time I was into electro and stuff like Vangelis, Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream and Jarre.

When did you first think to fuse piano with dance music?

I played the piano from a young age and eventually ending up at Trinity College of Music. By then I was well acquainted with contemporary experimental music, and never had a problem reconciling it with groups like Underground Resistance and the Jonzun Crew. It was never one or the other. I tried producing electronic music on an Atari with Notator but missed the feel of playing an instrument, so I left it. About six years ago, I decided to finally, once and for all, find a way to combine what I always wanted to do: electronic music production and playing. I ditched the computer and dumped a mic and speaker inside the piano and went from there.

At what point did you start working with prepared piano?

Right at the beginning, when I was trying to make a kick, which I really just see as a way to shape and control low-end energy. I was trying to make my piano into a drum machine, figuring if I got that sorted I was halfway there. People are surprised, but I use very few preparations, and nothing out of the ordinary. To be honest, I find most prepared piano music dull and uninteresting.

For those who aren’t familiar with the concept of prepared piano, can you talk a little about what it is and the history of its use in music?

It’s the practice of adding objects to the piano, such as bolts, screws, nuts and rubber. The sound it makes is usually percussive, and you often lose the original pitch of the key. It actually goes back to the 16th century, but was really invented in its modern form by the composer John Cage

, while composing music for a choreographer. So its origin is rooted in dance music.

Can you tell us about some of the specific ways you prepare your own pianos? What do you do to create these sounds? Is it a trial-and-error process, happy accidents or a more structured approach to creating particular timbres?

The ‘kick’ involves a lot of Blu-Tack and a ruler, the ‘snares’ and ‘hi-hat’ bolts and washers, some felt for muted bass notes. I held normal drums as a yardstick which I had to equal and sonically surpass in some way. If the sounds were just clever copies, they would ultimately be useless – there had to be something new and unique about them to justify their existence. The difficult technical stuff is in how I get the sounds out of the strings and into the PA. That’s where the sweat, toil and frustration lies. I had to build my own hardware, and it took a long time. I have humbuckers the size of ladybirds…

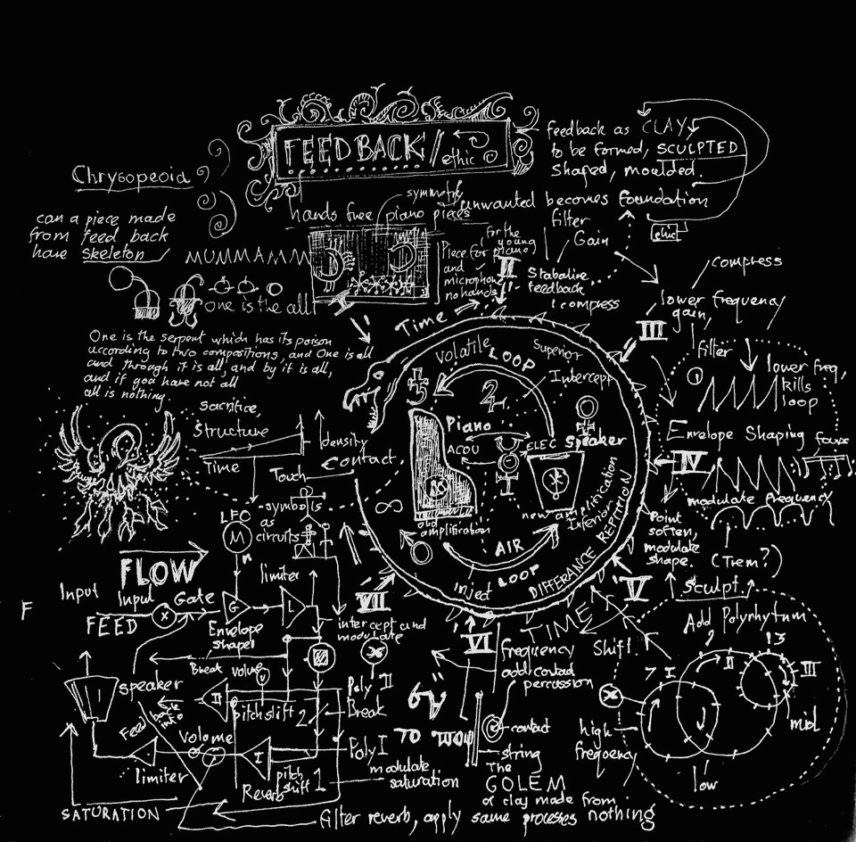

Preparations are just one factor. Extended techniques are just as important: hitting the strings, pulling with fingers, slapping, etc. Right now I’m in the final stages of putting another element in place, which involves using the feedback caused by the soundboard and PA as an acoustically generated ‘oscillator’ that I control and shape into rhythms and tones. The piano, room and PA becomes one huge instrument. It is early stages yet – I think I have already blown one of my Genelecs, and it completely ran amok in a gig in Holland last weekend – but when it works it sounds spectacular.

Diagram of the feedback system, using the piano, room and PA as a controllable oscillator

How many pianos do you use? I saw the portable electro-acoustic piano you set up recently. Do you have a lot of different instruments on the go at any given time?

I have separate rigs: a normal grand piano, a supposedly portable 150kg grand, the Yamaha CP-80

– perhaps one of the greatest electro acoustic instruments ever built – and a modified clavichord, a little keyboard from the 16th century that is compact enough to carry on the bus. It’s small but creates a sound as big as the others, and can quite easily bring a PA to its knees. They all sound different, and I am currently working on a CP-80 and clavichord album. I am particularly excited about my clavichord, as it is now largely a forgotten, obsolete instrument. Resurrecting it for a new audience is a great feeling, even if it is very technically challenging to pull off.

Everything you do is played live, in real time, with no looping or overdubs. Is that purely so that you can perform all the tracks in a live setting or is there more to it? Are you never tempted to loop, say, a kick drum-style sound so you can free up your fingers for more parts over the top of it?

No. It always sounds better when I record in one take, to a stereo file, with no mixing. Maybe because the whole piece is created in real time, as a whole, all the parts work together as one. This is how a pianist approaches a solo classical piece: bass, middle, treble, foreground and background, simultaneously. Sometimes adding is the easy way out of a problem – if the sound is good, you don’t need to add more.

How much does the setting of the performance affect the way people react to it? Do you think the type of venue you play in – and the way you’re presented on stage – has an effect on people’s expectations and responses to the music?

Thats a deep question, but basically yes, it does, and the setting is a big part of the musical experience. You can either go with it, or deliberately against it.

What kind of responses have you had playing live in a more dancefloor-focused club setting, like XOYO? How do people react to the spectacle? Is that dancefloor setting something that particularly interests you given your own interests in more traditional forms of techno?

I would like to do something like that again, and do it better. After all, the piano has been making people dance in clubs and bars for centuries.

I’m not particularly driven to seek dancefloor situations out, but then I’m not driven to perform in public in general. It’s very stressful, and usually falls short of what I intended. Most of the traditional techno-inspired tracks I perform only at home and are technical studies used to improve my timing and concentration. Much more fun than scales.

When people attempt to fuse dance music with classical music – or just acoustic instruments – it often ends up as a very cliched attempt to make dance music seem more ‘serious’. I’m thinking of things like the BBC Ibiza Prom or Hacienda Classical. What are your thoughts on that?

It depends what side you come at this from. I hear a lot of contemporary electronic and dance music that is successfully using sounds and textures that used to be found only in classical and experimental music. Richard Devine and Autechre [relate to] Parmegiani

and Stockhausen.

How do you avoid that kind of cliche?

I avoid cliche by seeking the longest path to any destination. I am also blessed with some very blunt speaking friends!

Klavikon plays live at Nonclassical’s ‘orchestral club night’, Rise Of The Machines, at Ambika P3, west London on Friday April 15th. Find him on Bandcamp and Facebook.