You probably don’t know the history of digital audio. Get familiar with Eventide’s story.

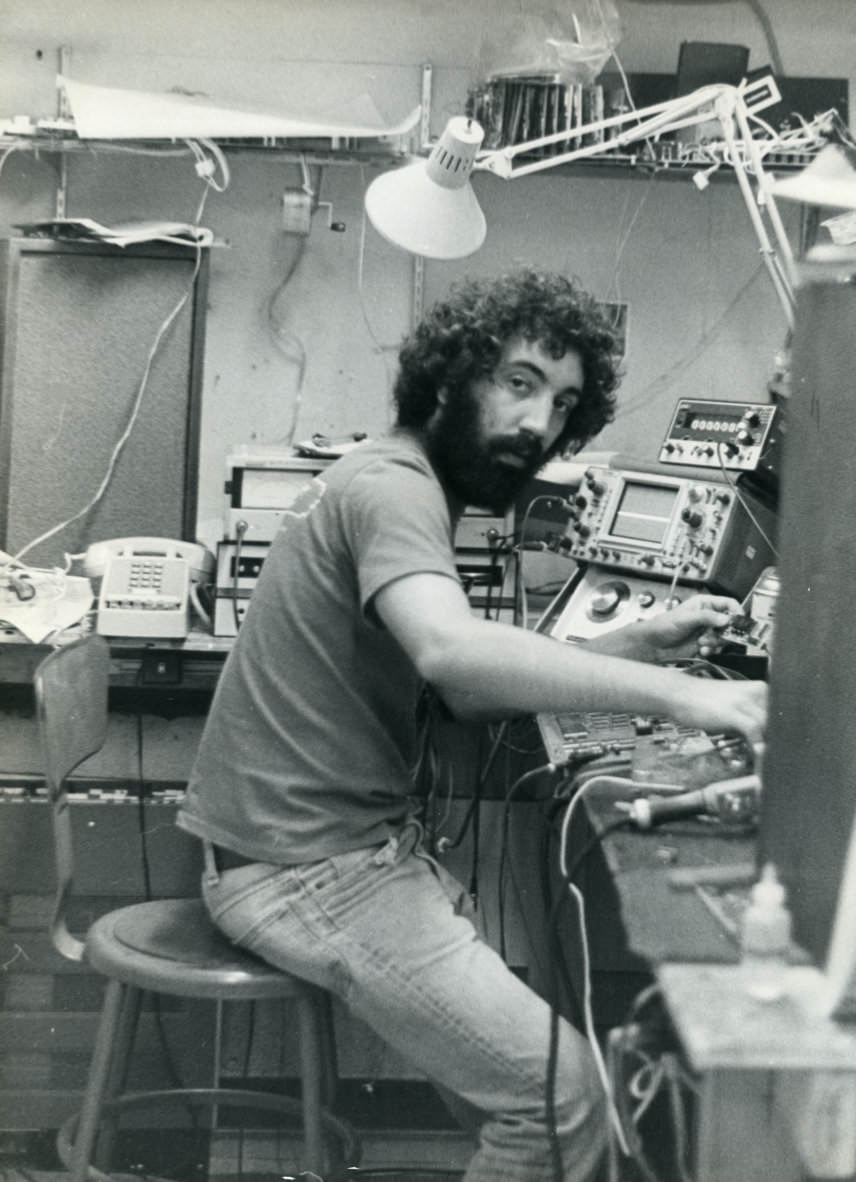

Tony Agnello (left) with Eventide co-founder Richard Factor

“The reality is that I was fortunate. I was in the right place at the right time.”

The place was New York, the time was 1970. Fresh out of university with a master’s degree in signal processing, Tony Agnello joined Eventide, a young company developing equipment for recording studios. Within a decade, Eventide had grown from a tiny basement startup to one of the main players in studio technology, ticking off various milestones along the way: the first ever digital studio effects; the first multi-effect unit; the first use of RAM in an audio device. They even invented the plugin – albeit in very different form to the software plugins we know today.

To cast our minds back to 1970, there were no digital audio products, full stop.

Despite the huge impact of the company’s products – most notably the Harmonizer line of effects units – the full story is rarely explored when we look back at the history of studio gear. Perhaps it’s because we all take digital technology for granted today that it’s so easy to forget this was entirely uncharted territory back in the early 70s. Digital audio technology was almost unheard of outside research labs and digital synths wouldn’t really make an impact on the mass market until the release of the Yamaha DX7 in 1983. Eventide were among the first to recognise the possibilities of digital audio, let alone develop commercial products.

Agnello puts the early days of Eventide into context: “To cast our minds back to 1970, there were no digital audio products, full stop

. None anywhere, in any recording studio, anywhere in the world. Zero. None of us had personal computers – this is before the first Apple computer or the IBM PC. I sound like an old fart, but back when I got started people didn’t even have digital watches. It’s hard to remember back to a time when semiconductors were brand new and LEDs didn’t even exist.”

Agnello at work developing the H910, circa 1973

Eventide is now based in New Jersey, but in the early years they inhabited a basement office on 54th Street in Manhattan, in the same building as Sound Exchange Studios. The company was founded by young inventor Richard Factor, recording engineer Steve Katz, and Orville Greene, a 60-year-old patent attorney with an interest in music. The latter were also co-owners of Sound Exchange, where Katz was chief engineer. Agnello joined shortly after the company was founded, working on an unpaid basis at first.

“I was fresh out of university having studied signal processing,” Agnello explains. “I was fortunate enough to meet Richard Factor about a year after he started Eventide, and he was already working on the first digital delay. There was very little practical signal processing back then, especially of audio in real time. I learned mainly by reading Bell Labs papers and books.”

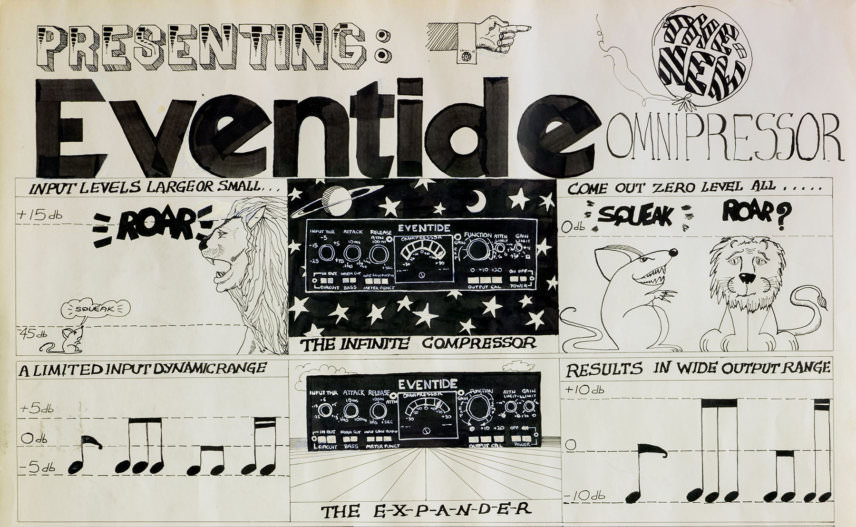

Eventide’s first two products were actually analogue devices: the PS 101 Instant Phaser, which used eight analogue filter circuits to replicate tape-style flanging effects, and the VCA-based Omnipressor compressor. “To this day, the Omnipressor is one of our favourites,” Agnello notes, admitting that it didn’t sell as well as the company had hoped. “We still wonder why it didn’t catch on more widely. People who bought it absolutely loved it.”

Agnello began work on the company’s first forays into the digital realm, helping Factor to develop the delay unit. “If you think about it, at that time people in recording studios could do pretty much anything they wanted in the analogue domain. The one thing that wasn’t really practical was delay. Folks who were doing double tracking were using two tape machines spread across the room. There’s no way that I know of to delay audio [cleanly] in the analogue domain. You could send it down a garden hose – there was a unit called the Cooper Time Cube which did that – but it didn’t sound very good and you had to cut the hosepipe to change the length of the delay…”

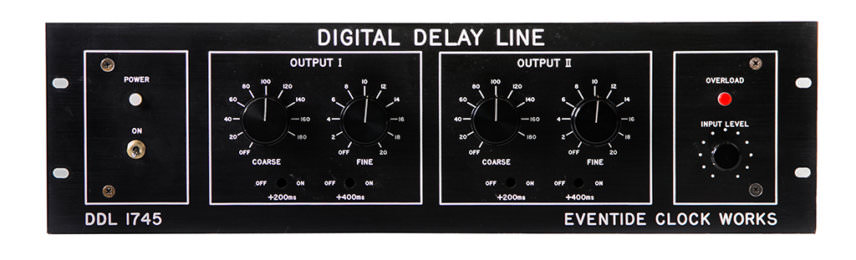

Eventide’s solution was relatively straightforward. “The first digital audio box was simply a delay line, nothing else. One of the reasons we were successful in selling that wasn’t so much because people were interested in delay, but at that point in the history of recording people were no longer using rooms and echo chambers for reverb because of the expense. People were buying EMT plates, which did a pretty good job of reverb but you miss that initial delay that occurs in a room. People were buying our delays to act as feeds to the plate.”

The technical side of that unit, the DDL 1745 Digital Delay, was primitive by modern standards but required serious effort to implement in the early 70s. In simple terms, there was an analogue-to-digital converter on the input, then the digital signal was fed into a line of shift registers, each of which delayed the signal slightly. A mechanical wafer switch on the front of the unit controlled the delay time by tapping into different points of the circuit. After that, a digital-to-analogue converter (DAC) brought the signal back into the analogue domain. There was no software, certainly no complex multi-tap options, and a maximum delay time of just 200 milliseconds. And it wasn’t cheap; the device sold for around $4,000 in 1972 (the equivalent of approximately $24,000 today). “Every time we shipped one of these things, it’s as if we were selling an expensive new car. It cost about the same as a Volkswagen Beetle.”

Every time we shipped one of these things, it’s as if we were selling an expensive new car. It cost about the same as a Volkswagen Beetle.

Following some success with those early products, the next big move for Eventide came about as a result of Agnello messing around in the studio after hours. “I had access to several of these digital delays and a full-blown multi-track recording studio, so I was able to haul these big boxes up to the studio and have many channels of delay; I probably had access to more delays than any other studio on the planet. Richard had designed a primitive pitch change module, so I could play with what would happen if you delayed the signal and fed it back on itself with pitch change. That was a kick. I thought to myself that instead of just selling a digital delay box I could design a box that had a bunch of effects using these digital techniques.” The result was the H910 (the name was a reference to the Beatles’ ‘One After 909’), a box which Agnello considers the first true digital effect unit (“the delay lines were more utilitarian”) and which kicked off the Harmonizer series that remains at the core of the Eventide range to this day.

In 1972, ten years before the release of the first Compact Discs and the establishment of the Red Book standard for 44.1kHz 16-bit digital audio, absolutely nobody had considered universal standards. “There was no notion of any kind of standard of sample rates. The whole digital system in the 910 was unstable; everything drifted and that was part of the charm. No two 910s sounded the same when they were new, and good luck finding a unit that sounds the same today as it did when it was new!” For the plugin version, Eventide engineer Dan Gillespie went back and remodelled every aspect of the original clocking system, including what Agnello describes as “the chaos”.

Agnello acknowledges that the 910 was by no means perfect, but it was really the only digital option around at the time, even if it didn’t always process the signal entirely smoothly. “I think we introduced the word ‘glitch’ to the [engineer’s] vocabulary,” he laughs. Following its release, Agnello spent around three years developing an autocorrelation scheme to improve the conversion and avoid glitches. The result was implemented in the subsequent H949, although not everyone thought the new model was an improvement: “One of the first artists who used the 910 on a record was Laurie Anderson. I remember when we sent her the 949 she was unhappy that the glitch was gone!”

“The 910 first started making us money in a very unpredictable way,” Agnello explains. Late-night television started broadcasting reruns of I Love Lucy. At that point, broadcasters had rules on how much commercial time they could have in an hour. They relaxed those rules for late-night television, so they were fitting in more commercials by speeding up the videotape. Lucy was running around a little more quickly than normal, but the pitch of her voice became really annoying. We started selling 910s to Channel 5 in New York and I couldn’t figure out why until someone told me they were using it to pitch-correct Lucille Ball’s voice.” Early studio adopters included Tony Visconti but with Eventide running very few ads it was much harder to spread the word to producers than it would be today thanks to social media and forums. “There weren’t many recording engineers who knew about it,” Agnello admits. “So we were actually selling most of these things to TV stations at first.”

The market didn’t really exist for the 910, but by the time the H3000 came out, there was the Publison, there was the Lexicon 224. Digital effects were starting to be everywhere.

Over the course of the late 70s and early 80s, the digital effects market started to grow. Eventide continued to develop new products, most notably the SP2016 reverb, released in 1982. “It wasn’t wildly popular,” says Agnello. “But it actually had plug-in ROMs to hold effects. I believe we coined the term ‘plugin’ [in a musical context].” To help develop new products, Eventide hired young engineers Ken Bogdanowicz and Bob Belcher, now CEO and lead engineer of Soundtoys respectively. Their work on digital signal processing represented a major step towards what we now think of as a modern DSP-based effects unit, resulting in the release of the H3000 Harmonizer, which remains one of Eventide’s most celebrated products.

By this point, engineers and producers were beginning to understand the potential of digital effects: “The market didn’t really exist for the 910, but by the time the H3000 came out,

there was the Publison, there was the Lexicon 224. Digital effects were starting to be everywhere, and the 3000 was just a great implementation of all that technology. It leveraged all the stuff we did in the 2016. It’s a great box.”

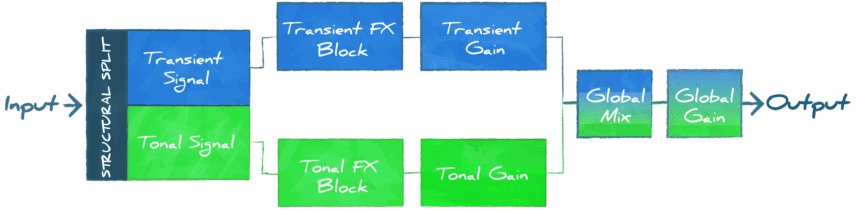

Incredible as it is to think that the company is now nearly half a century old, Agnello remains hugely excited by innovation and pushing forward with new technologies. He’s particularly enthused by the work the team are doing in developing the new Structural Effects, which can split the signal into tonal and transient components in real time, allowing them to be processed separately then blended back together. “We have some really bright DSP developers and what they’ve come up with just blows me away. It made perfect sense for us to recreate some of the iconic products in plugin form, but that’s not where we want to live. Our real interest is pushing forward with things that weren’t possible before. It forces you to be at the cutting edge.”

The Structural Effects signal flow

Agnello is almost infuriatingly humble about his own achievements and the role that Eventide have played in pushing forward digital audio. At every point in our conversation he’s keen to play down his own involvement and praise the efforts of those around him. In a rare moment of pride, he allows himself just one moment to reminisce about how difficult it was to develop the company’s groundbreaking products back in the early 70s: “There were no computers for laying out schematics or printed circuit boards. That didn’t exist in our world. Schematics were drawn by hand and circuit boards used mylar tape and single-edged razor blades. I laid out the 910 circuit boards at night in the bedroom of my apartment in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

“I like to say that I did simple things and I was fortunate. I was in the right place at the right time. But it wasn’t easy.”