In many ways, it’s understandable. We live in an era defined by short-termism. We’re easily bored. Trends change as quickly as they form. Besides, as producers, after the thousandth listen to a carefully crafted drum loop, who isn’t tempted to move on to the next project? Do we really spend as long as we should experimenting with different compressor models and EQ settings? Or auditioning different drum sounds? One can’t help but feel that if we gave the kind of dedication to our tracks that the past masters did theirs, our output could be better.

We live in an era defined by short-termism. We’re easily bored.

But there’s a notable caveat to this quest for perfection. Bill Bottrell spent close to two years of his life working with Michael Jackson, where there were constraints on neither the budget nor the timescale. Imagine working on that kind of project!

Yet here’s the thing: shortly after completing his work on Dangerous, Bottrell quit the pop machine – whose goal was total perfection – and returned to his roots, making and mixing country music with a far rootsier, far less contrived edge. The move was a rejection of the mechanism of perfection to return to the soul of the music – something more human by far.

Bottrell’s experience offers an interesting insight into how far we can – and should – go, revealing that the law of diminishing returns applies to perfectionism in music production. Maybe, as Leonardo da Vinci concluded five centuries back, the best pieces of art are never finished, only abandoned.

5 – It’s bloody hard work

Across the 68 chapters of Classic Tracks, very rarely did I come across a lazy artist. Or engineer. Or producer. In fact, there wasn’t a single creative person profiled who hadn’t worked bloody hard to get where they were. It was, in the end, the most common thread of all.

Of Madonna, producer Jason Corsaro said: “She is smart, capable and very focussed, and she made sure that everything was exactly how she wanted it.” Of Nirvana, recording Nervermind, Butch Vig revealed: “The guys told me they’d been rehearsing every single day for the past three months… They were serious about wanting to make a really tight, really focussed record; the slacker-rock mentality didn’t apply to that band.”

These were people who loved and breathed music. But more importantly, worked music. Relationships, domestic contentment, sideline projects… all were sacrificed on the altar of creativity. Sessions frequently lasted long into the night. On Rumours, Fleetwood Mac worked 14- and 15-hour days. It was a workload made possible by a little chemical help, recalls engineer Ken Caillat: “We felt like we weren’t getting enough done… so coke seemed like a good solution. We were all in it together – working ’til we dropped.”

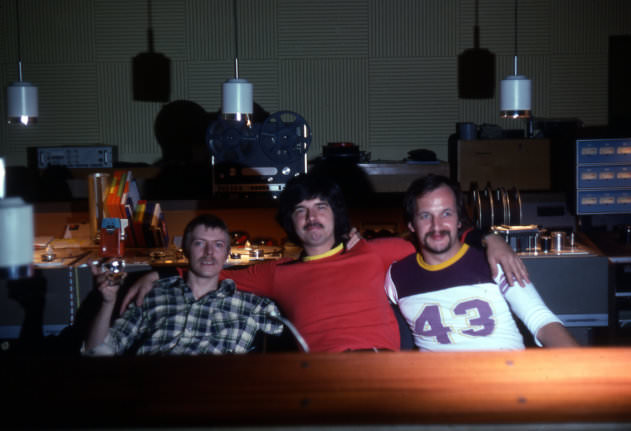

David Bowie in Hansa’s Studio Two

David Bowie – legendarily – went even further. For him, there was no downtime at all. “Working with Bowie is much more than going to the studio,” noted long-time collaborator Tony Visconti. “It’s a social event too. We eat together, go to shows together, go to clubs together and really soak in the local culture. That’s always been his way of working…” It’s as if the album is the end result of a period of creative isolation and cultural absorption; the daily business of living gives rise to the album.

Countless recording sessions were marred by serious disputes, but the artists’ underlying commitment to the music ensured that projects were eventually completed. The truth is the same as it always has been: that those who keep at it, day after day, who may (occasionally) compromise on their vision but never their dedication… these are the people who still rise to the top.

Suffice to say, I ended the book with an ever greater respect for a group of people I already respected hugely. And also a level of inspiration for writing my own music that had been missing for some time. For their many, many imperfections, these stories from the past provide the best kind of examples for the music makers of today to follow.

06.54 PM

Great and inspiring article1

01.57 PM

What a fantastic subject to read about. I’m working on a track right now and I thought I’m taking ages knowing that the most parts were written in an hour. I’m not saying I’m writing a classic but I want every part of it to be good enough to be part of the track/song. Transitions, drops, fx, vocals, mixing, levels. Everything. I rather write 10 good songs in my life than 100 crappy ones.

05.53 AM

Yeah man.

Make dance music without trying to sound like dance music.

08.34 PM

Nice article. But I need to point out that Dire Straits didn’t have an album called “Money For Nothing”. It was called “Brothers In Arms”.

10.46 AM

Steve – I stand absolutely corrected. Text amended. Thanks 🙂