Unless you’re a major-league DJ or spend your life on the road the largest chunk of a musician’s earnings is typically royalties – from record sales, streaming, downloads and performances. But it’s an area that confuses many artists. In this exclusive extract from Attack’s latest book, Make Your Music Make Money, we identify the key royalty streams and reveal how to tap into them.

Some musicians’ income streams are easy to understand. They deal with the tangible. You play a gig – you get paid. You sell a 12 inch – you take the fiver. Royalties, on the other hand, are more conceptual and not as easy to grasp. But since they make up a significant share of a successful artist’s income it’s important to understand what they are.

The best place to start is by looking at how they came into being.

Make Your Music Make Money is available now from the Attack Magazine store for the introductory price of £6.99.

A Brief History Of Ownership

The term ‘royalty’ dates back to the 15th century. Back then rights were granted by the British monarch (Royalty, geddit?).

These ‘Royalty rights’ allowed individuals or corporations to exploit certain enterprises that were under the monarch’s control.

For several centuries, authors and composers were not thought to ‘own’ their work. Once written, it was on the wind. The people who were granted Royalty Rights, and made money from the works, were those who had the means of duplication and distribution – which meant printers and publishers.

The first example of what we would now think of as ‘copyright law’ is generally thought to be The Statute of Anne. (The reigning monarch at the time was Queen Anne. It required Royal Assent to be placed on the Statute Book, which it was on April 5, 1710).

The statute was designed to pass ownership of written work from printers to authors and was a big win for artists of all kinds. Because of Britain’s involvement in and influence over America at the time, the principle also took hold in America.

COPYRIGHT

What the statute did was to enshrine in law the rights of the creator of a work (author, composer or playwright) to licence that work to be copied (a right to copy… copyright) for general distribution in return for a share of the income.

The Statute of Anne didn’t specifically cover musical composition. But the potential was quickly spotted and the law grew in scope over the coming decades.

Then in 1842, The Copyright Act was enacted in the UK. This repealed all former laws and clarified that all authors – whether of books, music or plays – for the first time owned their work, and could therefore subsequently license and exploit it financially.

In the late 19th century and well into the 20th, this exploitation was dominated by sheet music. Songwriters would assign their rights to a song publisher who had the means of printing and distribution to hand. The publisher would take original manuscripts, duplicate them, distribute them and sell them before paying the original songwriter/s a share (royalty) of earnings.

It was a phenomenally successful model. Even in far-flung rural areas people would gather round their pianos to learn and sing the latest songs. Sheet music sold by the millions – and composers reaped the rewards.

The Next Royalties: Performance

Then things began to change. As populations left the villages and their cosy communal singalongs to live in towns and cities, people started congregating instead in music halls, burlesques and theatres to hear the popular music of the day.

No longer was music being enjoyed by a select few; it was being consumed by hundreds – sometimes thousands – at a time.

Those running the concerts were making small fortunes. But the composers were only seeing income from the few manuscripts sold to the musicians on stage.

Composers and their powerful publishers saw they were missing a trick. Other people were getting rich from the intellectual property they owned. They wanted to be paid each time one of their works was performed live. So they set about lobbying governments to ensure musical rights holders benefited financially not only from sales of printed music but also performances of that music.

The seed for this ‘right’ had been sown in France as early as 1777. A group of authors had formed a society to collect and administer money due to the ‘playwright’ from performances around the country. Fifteen years later, on January 19, 1791, that kernel of an idea was ratified as law by Louis XVI , establishing France’s SACD collection societié.

This became the model for today’s collection agencies – ASCAP and BMI in America, PRS, MCPS and PPL in the UK, and various other agencies in Europe and around the world. (See The PRS, and how to join, below.)

The PRS, and How To Join

The Performing Rights Society (PRS) is the UK collection agency that gathers payments from radio, TV, film and other public broadcasting sources on behalf of songwriters and music publishers. Every country has its own equivalent.

You qualify for songwriter PRS membership if you write and/or compose songs or music that is being commercially released and/or performed.

To register, go to their website and follow the links. It currently costs £100.

As a member you are accounted to four times a year and paid out according to their distribution formula. If you are signed to a publisher you will receive 50% of any income from broadcast of your music direct from PRS. The remaining 50% goes to your publisher, who will pay out the balance owing to you. If you self-publish you receive 100% of the payments.

In the UK, PRS has joined forces with what used to be a separate collection agency, the Mechanical Copyright Protection Society (MCPS). MCPS collects money from mechanical public performance (the playing of recorded music in bars, offices, etc) on behalf of record companies and publishers, and pays out to its members monthly.

When you become a member of PRS you are automatically eligible for royalties collected by MCPS, as long as your record company and publishing company are members. We advise you to check that they are before signing a deal.

Mechanicals Enter The Fray

As we entered the first quarter of the 20th century, it had become established that:

- songwriters own their own work

- they are entitled to share in sales of printed versions of that work

- and they are entitled to be paid wherever and whenever that music is performed.

But a new, even more significant revenue stream was about to open up thanks to a mechanical development that would shape music listening for the next half-century: the invention of the phonograph.

For the first time in history, the experience of listening to music was no longer dependent on human performers. Instead you could buy a mechanical (wind-up) machine (hence the term mechanical rights) that did the job for you.

There was no way the publishers were going to be cut out of that particular piece of pie, so in the UK The Copyright Act 1911 consolidated all prior legislation and conferred copyright on sound recordings as well. Because the British Empire was at its height, the act reverberated internationally.

Exposure And Royalties: The Radio Effect

Radio has traditionally been the biggest medium for promoting popular music. And while it might now be feeling the heat from streaming services, radio remains a linchpin of income for songwriters. So it’s strange to contemplate its humble beginnings – as wireless telegraphy, often conducted along railway lines.

In 1873 James Maxwell predicted the possibility of wireless electromagnetic waves. Fifteen years later Heinrich Hertz gave the first practical demonstration of what had become known as ‘radio’ waves.

Then a young Italian named Marconi began experimenting with ‘broadcasting’ – sending these signals more than a few feet. It wasn’t long before he was able to transmit across a distance of up to two miles – and over hills.

By the mid-1920s, these small beginnings had grown into the start of the American commercial radio system. Restrictions on the distance wireless signals could travel meant that AM stations eventually numbered in their thousands, serving local communities rather than a national audience.

As they began to find big audiences for music, so the rights of songwriters and recorded versions of their songs – already enshrined in law – began to add to musicians’ earnings.

Also, being local, they found more success playing to local tastes, which is how country music and R’n’B found their way into the mainstream. But the dominant AM format was Top 40 radio which, over three decades after World War 2, built a massive market for sales of singles.

Then, in the 1970s, along came FM radio, high definition and stereo. DJs began to play album tracks – even whole albums – which helped shift record sales from singles to albums. In little more than a decade FM had 70% of the audience and the AM Top 40 format was on the way out.

Today, FM radio remains as popular as ever, supplemented with thousands of online stations catering to all manner of tastes, the best known being Apple’s Beats 1.

Seeing the potential for pushing sales of singles and albums on iTunes via their own online station, Apple launched Beats 1 in June 2015, running 24 hours a day, and anchored and ‘curated’ by DJs Zane Lowe, Ebro Darden and Julie Adenuga. Beats 1 is part of Apple Music, which has over 56m paying subscribers, making it potentially the biggest radio station in the world – though Apple have never revealed listener figures.

One thing’s unarguable, though: the importance of radio exposure and royalties for artists at all stages of their career, from emerging talent to global stars.

21st Century Rights

The history of intellectual property has been characterised by societal, technical and consumer developments repeatedly changing how people use and pay for their entertainment.

Usually the existing rights are simply rolled over or expanded upon to take account of the new circumstances. But occasionally a tussle ensues. It happened with video when film studios decided there was no precedent for paying actors and writers for viewings at home. Actors and writers went on strike, so no new film or television shows could be made. That solved that problem.

Now it’s happening with streaming – discussed later in this chapter.

But even though the way we consume music today may seem a million miles away from our forebears with their dusty phonographs, the principles and rights established a century ago are pretty much unchanged.

They are that:

- As a songwriter, you own your work. It is for you to agree terms with a publisher who can exploit that work financially. (Or not, in the case of artists who self-release and self-publish.)

- As a songwriter, you are entitled to share in revenues from the sale of sheet music, in the broadcast and performance of your work in public, and from sales of that music in mechanically reproduced (recorded) versions.

More specifically, as a songwriter you are entitled to a share of revenue from:

- all sales of recordings of your songs, whether by you, or cover versions

- all broadcasts of your music (on radio and TV)

- all paid-for streams of your music

- all public transmission of your music (in bars, workplaces, shops, telephone ‘hold’ music etc)

- all live performance of your music, not only by others, but also from your own gigs

- ‘sync’ deals (one-off uses of your song in a commercial, or as soundtrack in a film or TV show).

All of which is to say take control of your songwriting. The Song (and Songwriter) rules supreme. It is, and has always been, where the serious money is.

That’s not say there’s no money elsewhere. Performers – those who are contracted to play and sing on the recording, whether a solo artist or a band – also have rights, and are paid royalties in certain territories. (America is a major exception.)

But they are not afforded the same financially elevated status as creators of the work they perform.

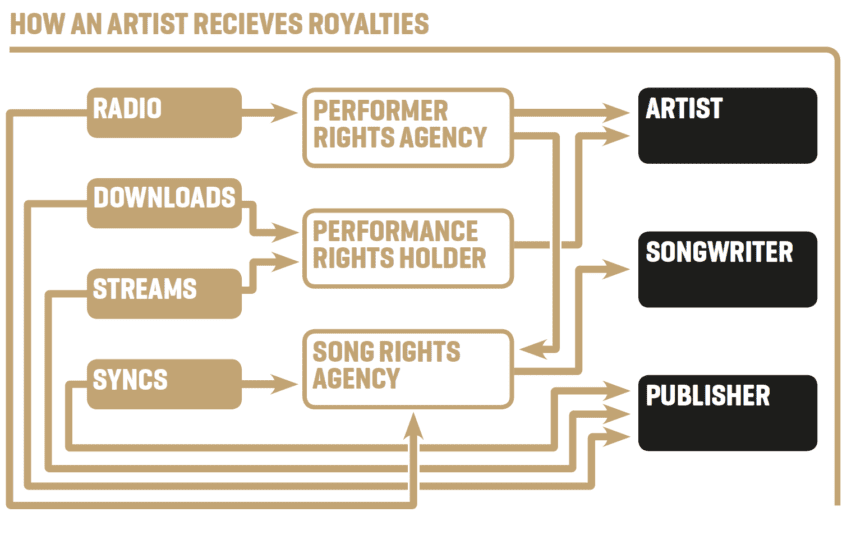

Paying Out Royalties

Here’s a breakdown of the payments you will receive and from what source they will come when you make a recording of a song you’ve written that gets played on the radio and/or sells copies via retail.

- From your label you receive a royalty, based on record sales and streams (both physical and digital), as the artist or band contracted to perform on the record. Labels typically pay out royalties twice a year – but this will depend on the record deal you’ve signed.

- From your publisher you receive a royalty as the writer of the song on the record. Publishers generally pay out twice a year.

- From your local/own country’s songwriting society (PRS in the UK), you receive a royalty as the writer of the song each time it is played on radio or TV. Half is paid to you direct and half goes to your publisher, which then accounts to you for your share. Songwriting societies typically pay out quarterly. In the UK, for example, the PRS distributes royalties in April, July, October and December.

- From your local/own country’s performance agency (PPL in the UK – see PPL: How it works and how to become a member, below), you might receive an additional royalty as the performer on the record each time it is played on radio or TV. (As noted above, some countries, including America, do not pay a broadcast royalty to performers.) In the UK there is a main annual payment from PPL for UK income, while money generated internationally and from additional rights is paid at intervals throughout the year.

How collection agencies work – and where they’re going

The way agencies around the world collect and distribute the money they collect differs from continent to continent and country to country.

In the digital age the process also differs from how it used to be – and not necessarily for the better.

In the UK, for instance, there used to be periodic negotiations to agree how much a radio station would pay for each record played. Then each station would report every play of a record making it easy to tot up the number of plays multiplied by the per-play fee.

Today, there are so many more radio stations around the world and so many other sources of income from public transmissions (bars, cafés, vape bars, etc) that radio stations and other outlets generally pay a one off licence fee.

How much they pay for a licence depends on a range of factors. A radio station, for example, will pay a fee based on the size of its audience and the number of records played in each broadcast hour.

Some stations are still able to report per play, per record (known as ‘by census’). Others are not. And here’s where it gets a little unfair. If your record is not played by any ‘census’ station, you are unlikely to receive much, if any, payment for radio play because the play/s will not show up in any data.

This is because any rightful royalty payments from those that don’t account ‘by census’ will be masked by an algorithm which works on the pattern of play you have received from those that do.

Your local (own country) collection agency, once you have joined, will let you see which stations account ‘by census’. Make sure you and your pluggers concentrate on those stations.

And that’s where we’re going to stop trying to explain how collection agencies calculate how much to pay. It would be a book in itself – and a lot bigger (and more boring) than this one.

We could point you at an existing book – like Ron Sobel and Dick Weissman’s Music Publishing: The Roadmap To Royalties. But first off, it’s $45. Secondly, it’s seven years old. And thirdly… Haven’t you got a song to write?

Understanding the intricacies of collection agency algorithms is unlikely to make you a penny richer. Leave the royalty academia to Mssrs. Sobel and Weissman and concentrate on your career. It will be time far better spent.

The most recent development in recording music usage comes courtesy of the underground club scene. Electronic music played by DJs in clubs has always been a near-royalty-free area.

Not that anything too wicked was going on; just that there was no reliable reporting method to make sure performance royalties made their way into producers’ pockets.

But technology is changing that – although there is still no concencus over a universal method.

Pioneer has its Recordbox which is helping producer-DJs track their music in clubs. And then there’s Imogen Heap’s visionary Mycelia Project, which aims to link all creators to their earned income more directly and more quickly.

Meanwhile in the sync and library world services like Tunesat are constantly scouring TV channels and websites to track music usage and ensure writers and their publishers are paid accordingly.

We bet it won’t be long before something like Mycelia’s blockchain is applied across the board, including worldwide radio play and streaming. The revolution may not be televised, but it will be recorded.

In the digital age the process also differs from how it used to be – and not necessarily for the better.

In the UK, for instance, there used to be periodic negotiations to agree how much a radio station would pay for each record played. Then each station would report every play of a record making it easy to tot up the number of plays multiplied by the per-play fee.

Today, there are so many more radio stations around the world and so many other sources of income from public transmissions (bars, cafés, vape bars, etc) that radio stations and other outlets generally pay a one off licence fee.

How much they pay for a licence depends on a range of factors. A radio station, for example, will pay a fee based on the size of its audience and the number of records played in each broadcast hour.

Some stations are still able to report per play, per record (known as ‘by census’). Others are not. And here’s where it gets a little unfair. If your record is not played by any ‘census’ station, you are unlikely to receive much, if any, payment for radio play because the play/s will not show up in any data.

This is because any rightful royalty payments from those that don’t account ‘by census’ will be masked by an algorithm which works on the pattern of play you have received from those that do.

Your local (own country) collection agency, once you have joined, will let you see which stations account ‘by census’. Make sure you and your pluggers concentrate on those stations.

And that’s where we’re going to stop trying to explain how collection agencies calculate how much to pay. It would be a book in itself – and a lot bigger (and more boring) than this one.

We could point you at an existing book – like Ron Sobel and Dick Weissman’s Music Publishing: The Roadmap To Royalties. But first off, it’s $45. Secondly, it’s seven years old. And thirdly… Haven’t you got a song to write?

Understanding the intricacies of collection agency algorithms is unlikely to make you a penny richer. Leave the royalty academia to Mssrs. Sobel and Weissman and concentrate on your career. It will be time far better spent.

The most recent development in recording music usage comes courtesy of the underground club scene. Electronic music played by DJs in clubs has always been a near-royalty-free area.

Not that anything too wicked was going on; just that there was no reliable reporting method to make sure performance royalties made their way into producers’ pockets.

But technology is changing that – although there is still no concencus over a universal method.

Pioneer has its Recordbox which is helping producer-DJs track their music in clubs. And then there’s Imogen Heap’s visionary Mycelia Project, which aims to link all creators to their earned income more directly and more quickly.

Meanwhile in the sync and library world services like Tunesat are constantly scouring TV channels and websites to track music usage and ensure writers and their publishers are paid accordingly.

We bet it won’t be long before something like Mycelia’s blockchain is applied across the board, including worldwide radio play and streaming. The revolution may not be televised, but it will be recorded.

Royalties From Record Sales

If you’ve made it this far, put the kettle on and give yourself a pat on the back. You now know more than many musicians do about the how, when and why of royalties.

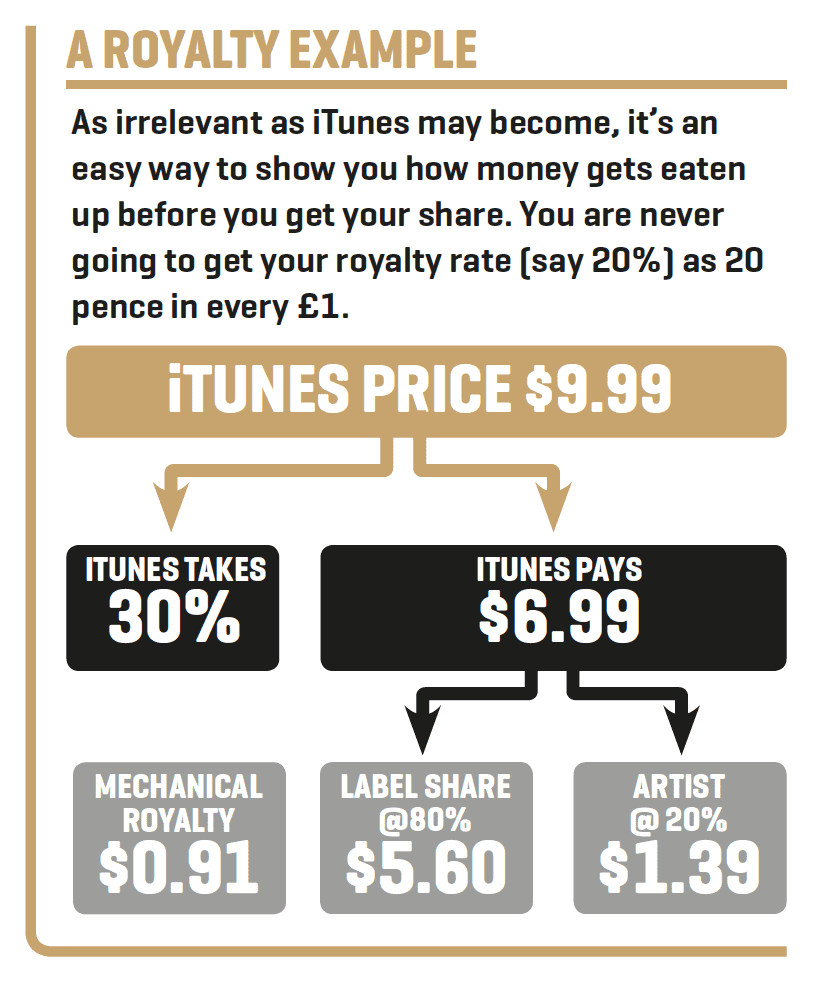

In many ways royalties from the sales of your music under a record contract (the money you make every time a CD, record or download is paid for) should be the easiest of all to understand – after all, don’t you just get a straight percentage of the income?

If only it was that simple…

Here’s what actually happens.

The label signs you as an artist. The record contract gives them the right to make copies of your work, either physically or digitally (usually both), and then pass on a percentage of the royalty made from sales to you the artist. This rate of royalty is enshrined in your contract with the record label. Let’s say the royalty is 20%. (If anyone offers you less than 20% royalty on a record deal, run a mile.)

So far, so good.

But: 20% of what? This is the million dollar question – or, more likely, not-a-million dollars.

And it is the cause of ongoing grumpiness among artists.

Let’s forget for a moment that iTunes is on its way out, because it’s a really simple example of how your end of the money diminishes in any payment system before it gets to you. So, you might think, for instance, that at 10%,

you could expect 99 cents for every $9.99 album downloaded via iTunes.

But you’d be wrong. Here’s why.

The album sells for $9.99 on iTunes – see diagram, below.

iTunes takes 30% of that as their share, leaving $6.99.

91 cents of that is mechanical royalty – an automatic payment that goes directly to the publisher of the song.

This leaves $6.08 for the record label. And it’s on this $6.08 that your 20% artist royalty is paid – just over $1 an album.

Which is why so many artists wonder why they’re still on the breadline even after selling 5,000 albums.

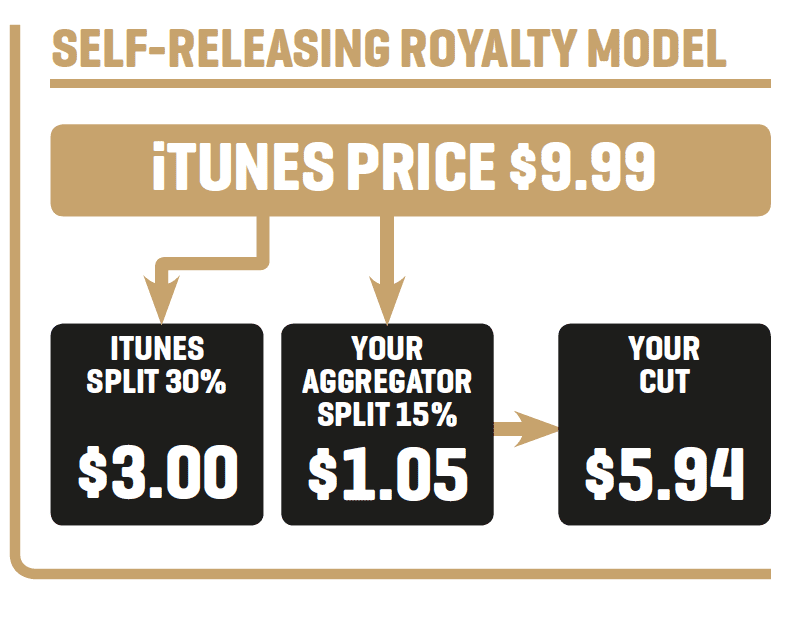

A Note About Self-Releasing

All of the rights (and subsequent royalties) outlined so far in this article are the same whether you release your own material or release through a label. The difference is that if you have a label and/or a publisher, you assign some of these rights (and therefore income) to other people.

When self-releasing a song digitally the model outlined above changes as follows:

- iTunes (or other retailer) will take their cut – typically around 30% of RRP (see imnage, below).

- You will then pay somewhere between zero and 15% to an aggregator (we talk more about them in Make You Music Make Money: Chapter 5 – Releasing a record) of what’s left.

- After iTunes and the aggregator take their cut, the remainder is yours (assuming you are also the songwriter and are self-publishing).

Your aggregator will have their own payment schedules, but they tend to be more regular than record companies and collection agencies.

- Which means that with an album RRP of, say $9.99, you can expect to see around $6 per album – a big improvement on the 60 cents typical under a record deal.

But everything is relative. One million copies at 60 cents is worth ten times 10,000 copies at $6. And a million album sales will up your live audience from scores to thousands.

Note that not all aggregators charge commission. Some charge a straightforward fee for putting your tracks online. Extra services, like promotion packages, can cost extra. All of this is covered in Make Your Music Make Money: Chapter 5 – Releasing a record.

Performer Royalty

Performer royalty relates to a performance on a record. This is paid out to those who perform on the record – the singer, the guitarist, the drummer. It is different to the ‘performance royalty’ collected by PRS, BMI etc, which is specifically about the broadcast or other transmission (‘performance’) of your record in public.

Some countries, notably America, do not pay performer royalties. But where they are paid, you are considered ‘the performer(s)’ if you are the singer or band contracted to the record deal.

The organisation that collects this money in the UK is Phonographic Performance Limited (PPL).

Check online for your regional equivalent. The money collected by PPL is distributed among record company members and performer members once a year.

PPL – How It Works, How To Become A Member

PPL collects royalties from the same sources as PRS, but it collects on behalf of record companies and performers.

So if you are the performer on a successful record but did not write the song you can still expect a royalty cheque for radio and TV play, and public broadcasts of your record in bars, shops and factories.

As with PRS, joining PPL is easy. Go to their website and click on the Register Today link. Just fill out the form and follow the instructions. The main qualification is that you are demonstrably the contracted performer on a record that has been commercially released (as opposed to a session musician who was bought in for the day).

If you are self-releasing, the same process applies. But if you have cut in other musicians (in lieu of a session fee, say) then you also have to register their ‘interest’ in each track

Streaming: The Latest – And Most Controversial – Royalty

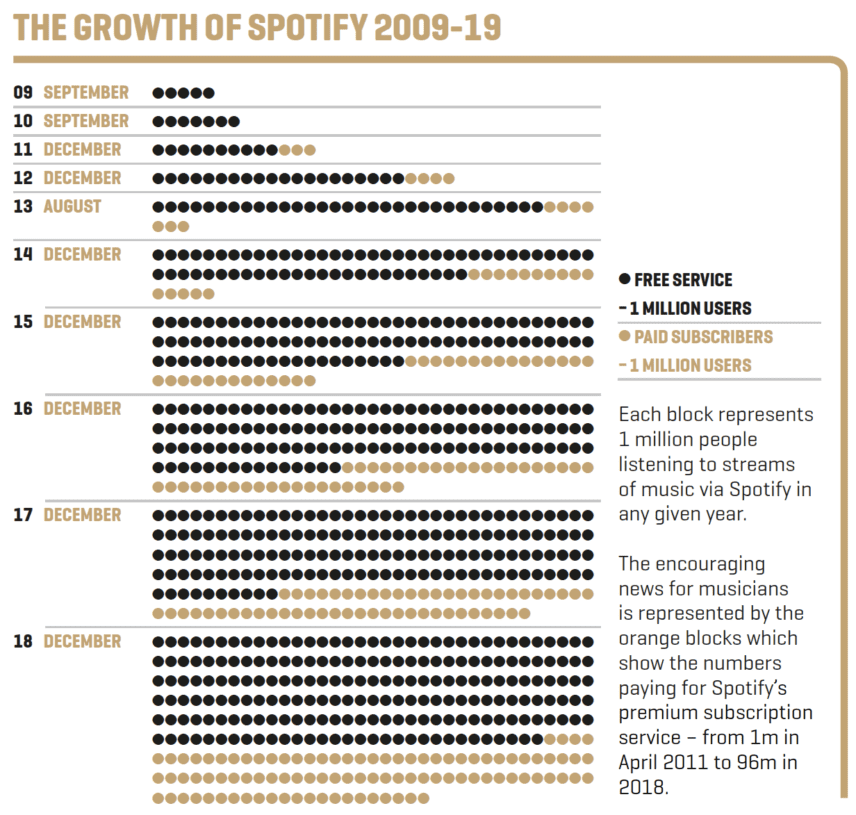

Streaming is the newest area of royalty earnings – and both its growth and importance to the industry have been phenomenal.

In 2008, in an industry turning over $15bn, Spotify contributed $500,000 – equivalent to 3.3%.

In 2018, in an industry grown to $19.1bn, Spotify contributed $8.9bn – equivalent to 47%.

And the move from digital to streaming is accelerating as Google Music battles with Apple Music. But niche services are growing too, including Deezer – which features live sessions in addition to recorded music – Tidal and Qobuz, both offering music files at CD-quality and better.

Subscription streaming is the future; Apple have staked their claim, and it’s no accident that the majors have a financial stake in Spotify.

But how does that translate to royalties for artists themselves?

Here things are more confused, with the unpalatable truth for some being that it doesn’t.

Streaming revenue relies on more complex models than those that govern traditional music sales (which, as we’ve seen above, can be complicated enough anyway).

The world’s biggest streaming service, by a country mile, is YouTube, for example. But, historically, YouTube hasn’t paid rights holders based on views of their copyrighted material. It has paid instead based on views and/or clicks of the advertising that is run alongside their uploads (the ads that appear at the start of a video or the banners that float over them).

As a consequence, YouTube has constantly been at war with rights holders who have rightly claimed the company only places monetary value on the number of ad views/clicks generated by an upload – rather than the number of views the music video itself gets, the very thing viewers are there to actually see.

But Spotify has – yet again – pointed to the future for a competitor.

YouTube has now introduced an ad-free subscription service. If Spotify, from a standing start, can garner 96m paying subscribers, we can only imagine what YouTube might achieve over the next five years with a 1.5bn user base to work with.

And the numbers are enormous. Dua Lipa’s ‘New Rules’ has been streamed on Spotify alone more than one billion times. On YouTube, the official video has been viewed more than 1.8bn times.

Ed Sheeran’s ‘Shape Of You’ video has had more than four billion views on YouTube and all but two billion streams on Spotify. Sheeran’s Divide album broke the pop charts when his streaming numbers meant he had nine placings in the Top 10 in March 2017.

But musicians haven’t been jumping for joy. Performers and songwriters have been seeing so little of the money generated from streaming their recordings that some (as we discuss in Make Your Music Make Money: Chapter 1 – The Music Business) have taken their music down.

One of these is Taylor Swift, who shows no sign of caving into the corporations. When she signed a new record deal towards the end of 2018 one clause written into her contract was that Universal would distribute – to artists – a share of any money it might make for selling its shares in Spotify.

The best way to view the controversies surrounding streaming is in a historic context – as the next big music-consumption shift that will require a new royalty payment solution, just like the invention of sheet music and radio and gramophone before.

Rights holders, musicians, tech companies, consumers, lawyers and even governments are currently jostling their way towards a solution. Throughout this process, musicians have been on the back foot. But signs are – sooner than expected – that power and financial balance is beginning to even out.

Since the principle of being paid for public performance of an artist’s work is well established, the big issue with streaming isn’t whether artists will be paid, but how fairly they will be paid and how it will be accounted for to artists and writers.

Is a stream like a sale (download) or a radio play? On that question, a lot of money depends. And if you are looking to be signed to a label, make sure your manager has the wit and influence to insist that your streaming royalties are paid at the rate of your headline royalty, not buried somewhere as either radio play or mechanicals.

But with giants like YouTube and Amazon and customers worldwide in their billions joining the subscription model, the future is looking a damned sight brighter than it did even four years ago.

By the way, if you are self-releasing (and self-publishing) 100% of the streaming revenue you generate will come to you via your aggregator.

As a signed artist, it will be included in your statements from your record company.