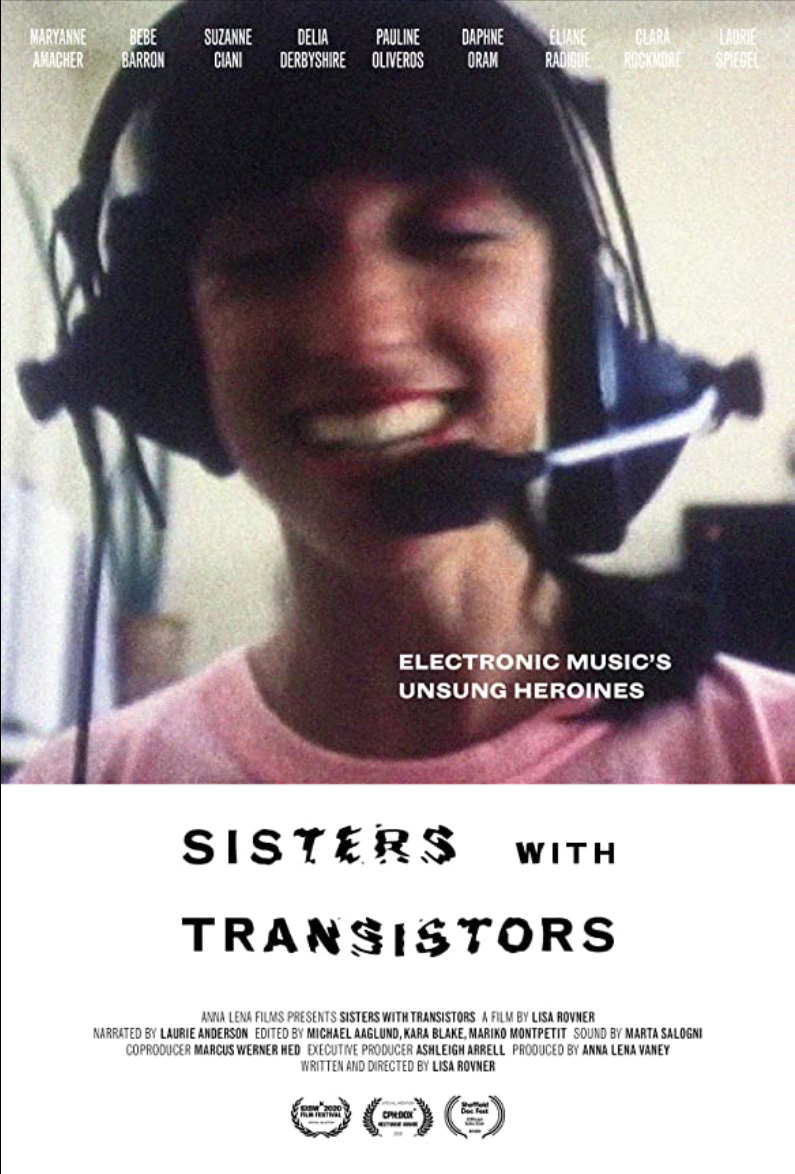

Sisters With Transistors: Electronic Music’s Unsung Heroes is a documentary that shines a light on the women frequently left in the shadows of this new music world.

The film can be jarring, both sonically and in story. The images, soundtrack, and narrative cut, splice, and loop back into each other. However, like the artists and music it reveres, the documentary moves with the same speed and electricity that the subject desires.

Eloquent and unexpected, Sisters With Transistors not only focuses on artists often overshadowed by their male counterparts, it also illuminates pioneers of sound and technology and the fearless foray they took into the newly electrified world.

It can get loud.

Technology is a tremendous liberator. It blows up power structures.

Laurie Siegal, Electronic Musician.

It can get louder still.

The history of women has been a story of silence, of breaking through the silence with beautiful noise.

Laurie Anderson, Narrator.

Cut to 1974

Suzanne Ciani is setting up to perform a concert in a gallery on a Buchla modular synthesizer. The dulcet tones of the black and white film in a white-walled gallery set the tone of the era perfectly.

She casually says the machine is, “probably the most sophisticated system that’s available. And I think they’re sensual.” Someone from the background asks, ‘they are what?’ She asks for a cigarette. She says, “Sensual.”

Sounding as casual as she did in 1974 she says in her current voice, “With this new technology… you were the sole arbiter of your creation.”

The music starts.

In black and white film grain she twists knobs, manipulates sliders and controllers. The rhythms and melodies evolve with the tiniest tweak of a slider and sweeping gestures across a touch-sensitive keyboard. This is a virtuoso pianist turning her back on the machines of the past, looking forward.

The audience, sitting on the floor in corduroy suits, wide lapels, and other era-specific choices, watches, transfixed. I shut my eyes for a moment and every sound is in color.

The music gets deeper, heavier, but not louder. Ciani continues on, her narration elegantly wrapped with the music and images. “The machine was alive.” “It was sensitive.” “It’s a much more open set of dynamics.”

Black and white Ciani twists a knob to silence and her overdubbed voice casually makes a statement that could have been made in that gallery in 1974; “In electronics, you are not dealing so literally with the architecture of notes or harmonies, those building blocks in the classical music… You’re dealing in energy.”

The performance is electric.

Cut to the 1920s

Clara Rockmore, a young Lithuanian violin prodigy who had toured Europe, emigrates to the United States. After developing tendinitis in her bow arm, she is forced to give up playing the instrument.

At the same moment, another immigrant is inventing his namesake, The Theremin. The touchless electronic string sounding instrument that can be considered the first real electronic instrument.

Leon Theremin and Clara Rockmore, the once virtuoso violinist, meet. They become admirers but not lovers. She becomes more than the world’s most well-known Theremin player; she is influential in refining how the instrument works.

You cannot play air with hammers. You have to play with butterfly wings.

Clara Rockmore

This story will play out more than once throughout this documentary. Other stories will break and even destroy more boundaries.

Splice to 1965. BBC Radiophonic Workshop

Delia Derbyshire sits before a bank of sound generators (oscillators), tape reels, and a giant oscilloscope. She turns up each sound generator and walks through what a sine wave, square wave, and white noise wave is, explaining the complexities of each waveform’s harmonics.

The scene is important as it sets the foundations of what is considered electronic music. It breaks the boundary of what electronic music is when she says, “We don’t always go to electronic sound generators for our basic sources of sound. If a sound we want exists already, for example in real life, we can go and record it. But those basic sounds aren’t really interesting in their raw state like this. To make them of value for a musical piece we have to shape them and mold them.”

Delia records a few sounds. She cuts the tape with a razor blade and splices each recorded tone with white leader tape, creating various tape loops that looks like Morse Code sounds.

A long bit of black tape, a shorter bit of white leader tape, a short bit of black tape, another bit of leader tape, a longer piece, a shorter one, alternating colors until the loop is done.

She presses play on one machine. The small recorded percussive sound gets deep when it is slowed down. She sync’s the next tape machine, increases the speed, and a different tape loop gets harmonic. Ultimately, she sync’s four tape machines, changing each of their speeds to get the right tone for each loop.

The groove is alive. The sounds did not exist until that moment. The band of tape machines makes music in a way very few people have done before. This is electric. This now.

Cut back to The Blitz 1940. Coventry, UK

Delia, at once a musician, a mathematician recruited by Oxford and Cambridge, and later the person who creates one of the first all-electronic theme songs for Doctor Who, says in overdub, “My love for abstract sounds were sounds of the air raid sirens because that’s the sound you hear and you don’t know the source of it as a young child. It’s an abstract sound and it’s meaningful and then the all clear… Well, that’s electronic music.”

Cut. Splice. Loop back to now

Suzanne Ciani says, “Part of an instrument is what it can do and part of it is what you do to it. The other part of music, of course, is the motion and the personal involvement… So, I play the synthesizer the same way somebody else would play cello or violin.”

There is a forbidden place Electronic music holds in the entity called the music world. Caught between the confines of what is considered real or traditional music, sounds made by human hands strumming strings on a guitar or pounding drums with mallets, and journeys into sound denigrated as repetitive machine-made noise best reserved for taking drugs and dancing to, electronic music is often disregarded, despised, or at best, tolerated as actual music.

In between that wide spectrum, both of which can be true, there are countless other virtuosos and brilliant knob twisters who embraced a 20th century phenomenon that grew out of the speed and energy of a newly electrified world.

The nine pioneers featured in this film did far more than help create the BBC Radiophonic Workshop when the BBC wanted nothing to do with electronic music or score the first all-electronic music soundtrack for a film (Forbidden Planet), they influenced the future, the future they heard in their now.

I grew up thinking Aphex Twin, Orbital, Stockhausen, and The Chemical Brothers were trailblazers. The innovators in this film influenced all of them.

They happened to be women.

Sisters With Transistors shines a spotlight on their spirit not just their shadows.

WHERE TO WATCH?

Watch the trailer on Vimeo or below:

World wide, screen the full film from April 23rd:

https://vimeo.com/ondemand/sisterswithtransistors

Watching in the UK?

https://www.modernfilms.com/sisterswithtransistors/watch

Watching in the US?

https://metrograph.com/live-screenings/sisters-with-transistors/