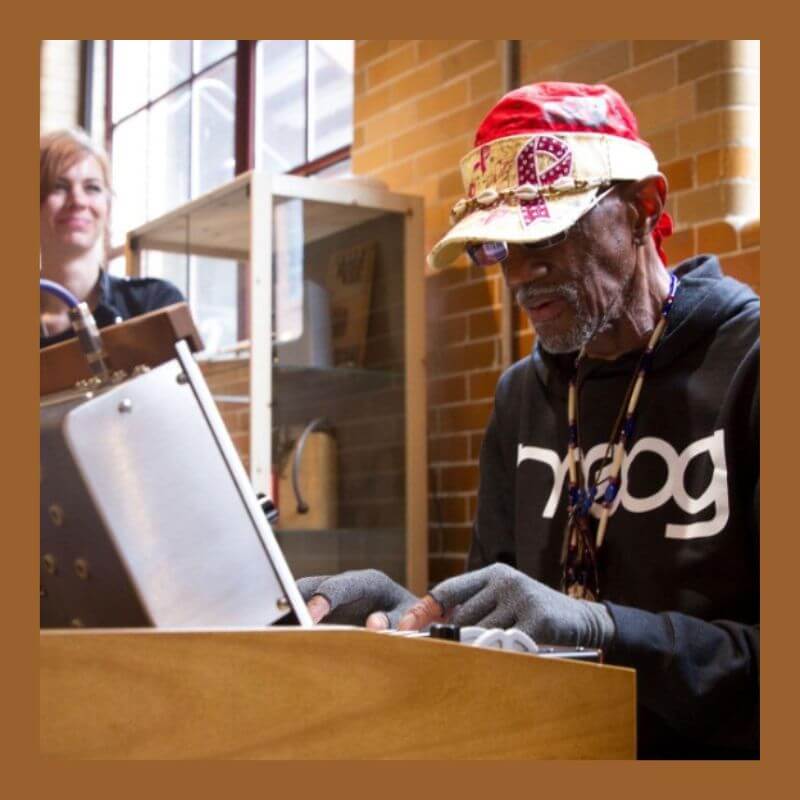

Darren Selement breaks down how the Model D went from a lunchtime concept to an icon. TLDR? The Minimoog is more important than the Les Paul…

Iconic, by definition, means widely recognized, well-established, widely known, and acknowledged for distinctive excellence. To paraphrase a well-known dictionary’s reference; Greek Gods and Wines all fall under this definition.

There are many synthesizers that can lay claim to float freely among the great wines and gods of the electronic music stratosphere. Off the top of my head and alphabetically, Arp, Korg, Moog, Oberheim, Prophet, Roland (Jupiter’s, Drum Machines, and Monophonic Synths) all have warrant. Toss in some famous samplers by first name (Akai, Fairlight, and Emu-Systems to list a few) and the anointed list begins to get crowded. Choices must be made. In my less than humble opinion, the list is much shorter than the above. It gets even shorter when revolutionary is attached to the definition of iconic. The docket gets downright minimal when the story of creating the icon is iconic in and of itself.

There is one machine, one synthesizer in electronic music, that is the epitome of iconic. The same synth that inspired Gary Numan to turn off guitars when he turned it on, pressed a key, and the studio rattled: The Moog Model D. a.k.a. The Minimoog.

Piecing together the Model D from scraps

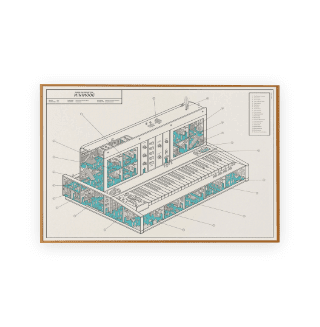

Initially invented over lunch breaks using parts culled from the Moog “graveyard”, engineer Bill Hemsath, along with help from Chad Hunt, Jim Scott, and others, built a hardwired single voice version of the enormous Moog Modular System. Encased in a relatively miniature box with a built-in keyboard and no need for patch cables the Min A, the first prototype of the Minimoog, did not fully capture Bob Moog’s attention. Behind the scenes and continually gravedigging for leftover parts, Hemsath tinkered as people began to talk around the shop.

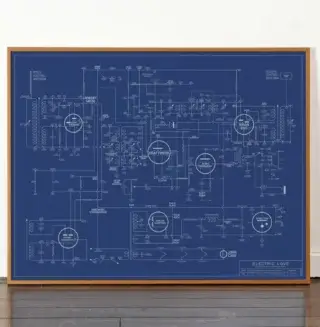

The original modular system Bob Moog created did not exactly have a wide scope of customers. Outside of the extraordinary cost to build and purchase, the giant and inventive modular system required the user to understand synthesis from the ground up. Those factors limited the machine to universities/colleges with electronic music labs, some high-end recording studios, and electronic music aficionados. Long story short, rock stars couldn’t tour with one, didn’t know how to use it, and thusly the common musician or fan probably didn’t know a thing called a modular synthesizer existed. If they did, they couldn’t afford one.

Electric guitars graced the covers of mainstream magazines, the pages of Sears catalogues, and some more ‘interesting’ spreads found in magazines not found in bookstores. The modular synth did not.

Faced with questions at Moog, financial included, Hemsath and the engineers revisited the Min A. The machine needed to reach out. The upgraded but downsized synthesizer they created pushed the accessibility envelope further. Pun Intended. The most important addition included the latch lid Bob Moog requested. The synthesizer was finally portable and easily made noise. Dubbed the Model B, Moog, the man and the company, embraced the new prototype.

Subtle and obvious, both aesthetic and sonic, more changes would follow.

Model B, C & D

The first circuits and a power supply designed specifically for this machine’s portability were a substantial evolution. The classic flip-top control panel inspired playability. The new machine, the Model C, was the first agreed-upon production model. 10 were ordered. Bob Moog went on a trip. Behind the scenes, and likely against Moog’s wishes, the inventors made concrete manufacturable choices.

The Model D was born. Along with a story that foreshadowed its future. Iconic.

The Minimoog is more important than the Les Paul. There wasn’t a Fender Telecaster to rival the Model D’s rebellion. Alone, the Minimoog transforms synthesis from a white lab coat world filled with knobs and plug bays and cables that resembled telephone switchboards to an instrument that would inevitably deliver modern synthesis to everyone.

Dictionaries should put a picture of the Model-D next to the word ‘Iconic’. They should do the same with ‘Revolutionary’.

Why all the history?

For a third time the Moog the Model D is back in production.

How do I review an icon?

I don’t. I won’t. The “new” Model D is exactly as it should be: Loud. Subtle. Breathtakingly beautiful. I turned it on, dialed up a full bass thump, and within an hour the neighbors called to say that their walls were rumbling incessantly, and the glasses in the cupboards were clinking like bad wind chimes. Their words weren’t quite as ‘artistically pleasant’ as the above, but the desired response happened.

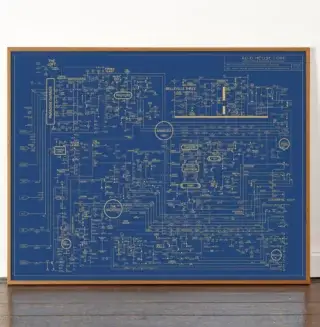

The knobs move spider silk quiet. The filter is everything and more. The rocker switches are silent when flipping oscillators on and off during drones. The dedicated LFO frees up the third oscillator to create a bevy of different sounds and modulations. The keyboard is fluid. Velocity and aftertouch allow for great nuance. For the first time Moog has included a spring back pitch mod wheel, which makes the machine even more playable. I’m not a prog rock musician or Herbie Hancock but I found myself channeling, vainly, some of their influence.

The machine sounds and plays as beautiful as it looks.

The machine has midi. It can send midi information like modulation, aftertouch, and velocity, among others. Despite being capable of receiving note information it cannot receive a vast variety of midi control information from a Sequencer or a DAW. Simply put, forget modulating every parameter with the vast number of VST Plug-ins (Shaperbox, LFO Tool, Gatekeeper, etc.) available on the market. There are CV Ins that account for some of those manipulations, especially if you have a great external sequencer with midi to CV conversion, but the absolute freedom to modulate at will is not available. I can hear the argument as I write the words: “This a Minimoog. It was built to simplify modular synthesis“. It was created to be played including the flip-up front panel. I agree. I just can’t help thinking what could have been, too.

I admit that I have a strange fascination with sending the headphone out of my Minitaur into a JHS Little Black Amp Box and using that as an attenuator to return the signal into the Audio-In to overdrive my Minitaur. The current Model-D solves a similar situation that existed on the original. Overdrive and feedback knobs and internal paths are provided. No extra cables or odd patching are required. Turn them up for that extra scream and thump.

Not quite last and not the least, the first ever wavefolder on a Moog, recently released on the semi-modular Moog Mavis, was not included. No, the Mavis does not sound like this machine whatsoever and I am not comparing them. I am also keenly aware that putting a wavefolder on a Model D would have fired-up controversy. Equally, it could have fired-up evolutionary sounds.

These missing features, along with some of the amazing aspects of a Moog Voyager, simple things like patch saving, make modernity feel neglected. (see above.)

That is not a complaint. Choices had to be made. The choices Moog made are pure. There is no synth that sounds quite like a monophonic, 3-Oscillator, Minimoog pressed into Overdrive with a tight Attack Envelope. Perfect to play, the latest release of the Model D remains iconic. It feels iconic. It sounds iconic. Ask my neighbors.

The price is iconic, too.

The dilemma the Model D faces

Hand built in Asheville, North Carolina, from the locally sourced Appalachian cherry cabinet and hand-finished aluminum chassis to the original signal path and naturally overdriven oscillators this machine is not a replicant. It is a 1:1 recreation of a synth that inspired and changed music. In many ways it reflects our current world at large.

Originally inspired to free synthesis from the ivory tower walls, the new Model D faces a dilemma.

Over time the electric guitar became as ground-breaking as a string quartet. Adding a few strings didn’t change its limitations. I’m grateful the Model D has returned to production 50 years later, but like the Les Paul it is no longer revolutionary in and of itself.

I’m sure that stellar recording studios will own one. Collectors will, too. I’m certain that brilliant musicians will find a plethora of ways to do justice to this version of the Model D and its fabulous nuances. In this modern world I fear the cost is prohibitive and that this beautiful machine could end up relegated to the Greek Statue Pantheon of the Baby Grand Piano in the living room, not serving one of its original intentions, synthesis to the masses.

I don’t condemn Moog for their choices on the new Model D. I couldn’t. The machine is perfect. So perfect that I was tempted to take it to task with certain VST versions I own. I didn’t. The VST is an appliance. The Model D is and will always be an inspired instrument meant to be played live. If I was Gary Numan, I would buy one today. Sadly, I didn’t write Down in the Park or Cars.

For more information visit Moog.

The Model D will be available soon on Thomann priced at £5,399.

If you like this article you may enjoy our Parliament Flash Light remake which was famously made on a Moog.

*Attack Magazine is supported by its audience. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more.

Darren Selement resides in western North Carolina, a short walk from Make Noise and a short drive to Moog. Divided but certain that if he threw a stone he’d hit a synthesist with an opinion on which approach was better, he is sure that from samplers to drum machines every choice is personal, and none are wrong. You can email him.