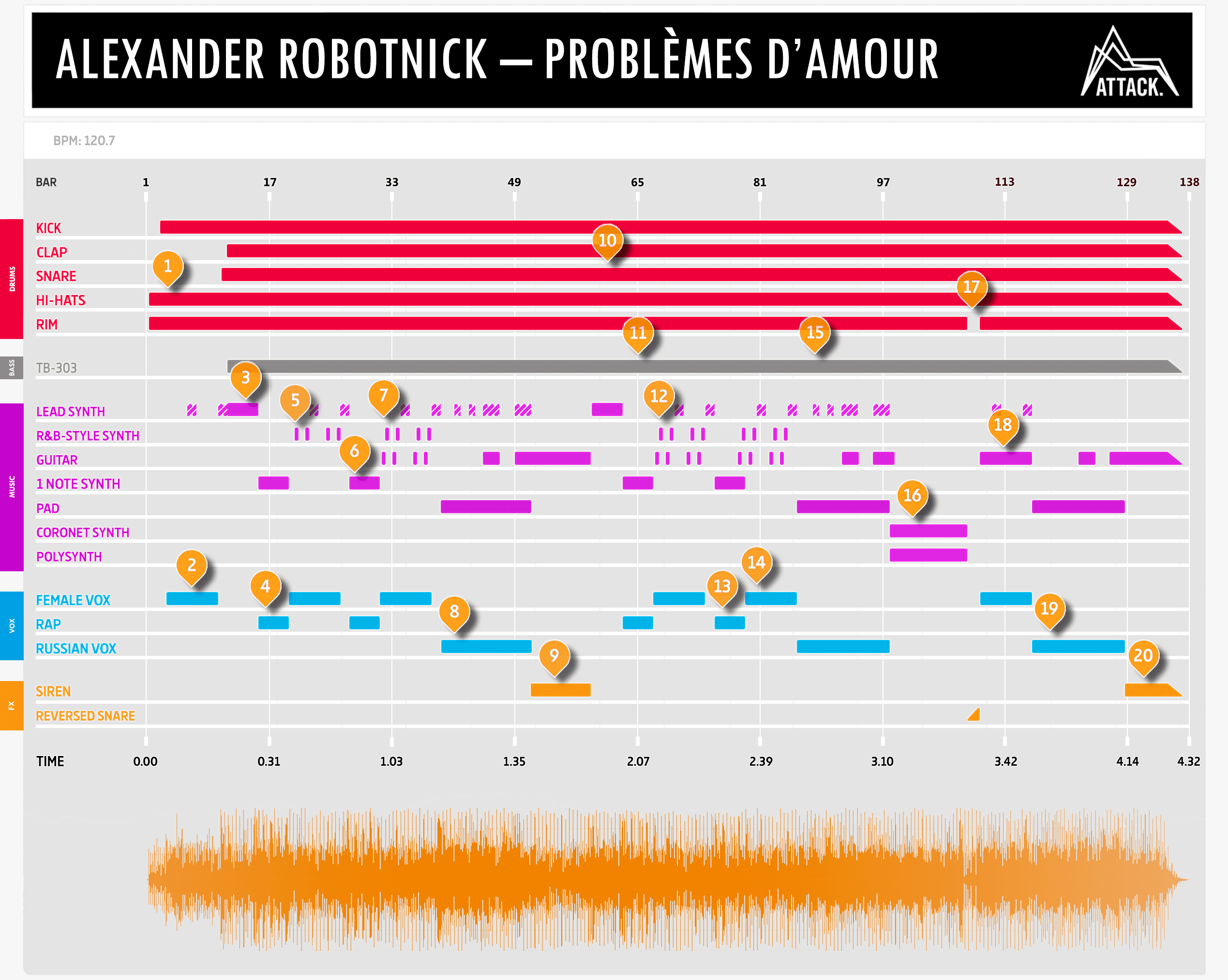

Deconstructed is an ongoing series where we take a close look at the arrangement of a dance song. This time, we’re examining Alexander Robotnick’s pioneering ‘Problèmes d’Amour’.

In 1982, an Italian by the name of Maurizio Dami took a record label’s advice and tried his hand at what was then still called disco. These days we’d call it electro or even Italo disco but in Europe in the early ‘80s, it didn’t matter what it was, if it had a 4/4 beat it would sell. Dami wired up his Roland TR-808, TB-303, and other gear, sang in French with a Russian accent, and started going by the name of Alexander Robotnick.

His first release, ‘Problèmes d’Amour’, wasn’t an initial hit. Although it sold what today sounds like a respectable 10,000 copies, in those days it was considered a flop. And yet its reputation only grew, thanks in part to a tough American remix courtesy Francois Kevorkian and its inclusion in the 1985 comedy, European Vacation. Having been rediscovered in the 2000s, nowadays it’s recognized as a classic of dance music.

What is it about this song that makes it such a classic, that keeps it relevant even in 2020? Let’s take a look at the unconventional arrangement and see if we can’t find out.

There are many versions of the song available. We’ll be looking at the album version, which appeared on the 1984 release, Ce N’est Q’un Début.

The Track

The Arrangement

What’s Happening

1

‘Problèmes d’Amour’ was released in 1983, before MIDI and rock-solid timing, so it’s difficult to pinpoint the tempo. This is likely because Robotnick used a TR-808 as the master clock. As anyone who’s used an 808 knows, there’s no LED screen to indicate tempo, only a large, unlabeled knob. Any additional editing would have nudged the tempo around as well (remember that in those days editing was done by splicing tape with a razor). All of this adds up to a tempo that we would consider fairly loose. It averages out to about 120.7 BPM but it varies slightly throughout the track.

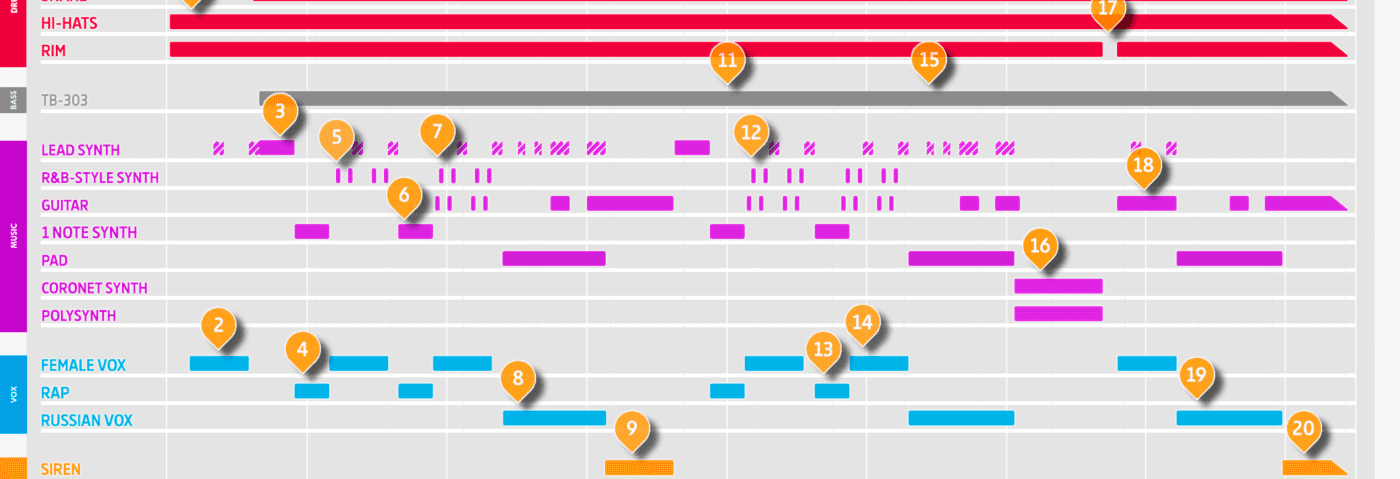

Another element that makes analysis of the arrangement difficult is the way the song starts. While most modern songs start with a definitive beat on bar one—hell, even old disco records start this way—Robotnick starts his in the middle of a bar with an off-beat open hi-hat. Take a look at the image above and you’ll see that because of this odd start, things don’t really stick to the grid. This is clue one to the song’s uniqueness.

It opens with a bare TR-808 playing a basic disco hi-hat pattern. The hi-hats run at sixteenth notes and fill every slot in the step sequencer, while the open hats are programmed to hit on the off-beats of 3, 7, 11, and 15. A distinctive 808 rimshot ticks away as well, panned to the left. It’s this rimshot pattern, which recalls American electro records, that helped classify the song as electro and separate it from the Italo disco of the era. Another clue.

2

Like many records of the time, ‘Problèmes d’Amour’ follows a standard verse/chorus/verse structure, just stretched out beyond pop music length to be more dancefloor-friendly. The album version actually starts with the chorus, with a female vocalist singing in French in the key of G minor. Robotnick completes the chorus with a sequenced synthesizer that plays in between the vocal lines. This is panned slightly to the right to give the vocals space in the stereo field. In terms of percussion, Robotnick adds a kick from the same TR-808 towards the beginning of the chorus, yet oddly not immediately. The song begins to groove. A snare fill appears at the end of eight bars to take us into the next section.

3

This four-bar section contains the main hook, with a sequenced synthesizer bobbing robotically up and down. It recalls both R&B and electro and yet is also very original. It’s actually two different synths, or at least one recorded twice, with each sound panned to opposite sides. It’s accompanied by the other song element that makes this song famous: a Roland TB-303. The 303 bassline is bouncy and consistent and underpins the synthesizer melody while also keeping the groove lively. Snare and clap sounds playing on the 2 and 4 of each bar complete the percussion section. Note that the rimshots have gained a stereo slapback echo now.

4

In another four-bar section, we’re given the verse, which is what could only be called a rap, although in French. There’s a ‘50s-style slapback echo treatment on the voice—certainly not a common production trick at the time. It’s accompanied by a synthesizer playing a single, sustained note, whose filter slowly opens throughout the section. The 303 plays a different, more subdued bassline, and additional 808 snares accent the rhythm.

5

Here is the first, full-length chorus section. From here on out, all of the choruses are eight bars long. As in section two, the chorus vacillates between female vocals and the sequenced synthesizer, although this time there is a higher, R&B-style synth line that fills the space after each ‘ah ou ah’ line. This also has some nice stereo separation. The 303 line from section three is back, with the 808 percussion mirroring that in section three as well. Robotnick uses a snare fill to propel momentum into the next part.

6

Another verse/rap, which is exactly the same as in section four. Robotnick has said that ‘Problèmes d’Amour’ was recorded in a non-professional studio with a 16-track recorder and mixer. “The result was a very dry sound”, he said in an interview with Red Bull Academy. It’s true that it’s not the most polished song but that’s what gives it its charm. Yet another clue.

7

Another eight-bar chorus. Note how the female vocals are doubled, with each take panned slightly apart and treated with reverb. This fills out the mix and makes the vocals seem wide. This chorus section is broadly similar to that in section five. However, instead of the R&B-style high synth between vocal takes, there’s a single-note guitar pluck that drops in pitch. Robotnick is likely playing these parts in live as there are slight variations in playing style for each one. Contrast this with the sequenced synth lines, which are uniform and robotic (pun intended).

8

Next is the bridge or middle-eight (although Robotnick, ever the joker, has made his 12 bars long). It’s quite full, melodically speaking, with a number of instruments involved. Robotnick sings in French with a Russian accent, accompanied by a synthesizer handling chords. The live synth appears again between vocal lines, providing a kind of counterpoint to the vocal melody. After about six bars, a guitar comes in, although it’s buried a bit in the mix. The 303 plays two new bassline patterns to underpin the melody.

An interesting aspect of the middle eight is that it modulates from the main key of G minor to B flat minor. This creates a feeling of change in the song without needing to add new instruments.

9

Here we’re back to G minor for an instrumental break. The 303 bassline plays the chorus pattern, filled out by the guitar that was introduced in the previous section. Robotnick was a jazz guitarist before he started making electronic music. He keeps it simple though, alternating between two chords. The main focus of this break is the siren-like synth, which rises and falls hypnotically. Siren-like sounds are great for increasing tension. At the peak of its second rise, it begins to loop, most likely done by hand-editing magnetic tape. A simple 808 snare fill ends the instrumental break.

10

Here we get four quick bars of the hook synth. Notice that the 808 patterns have not changed very much at all. Aside from a few variations in the snare pattern, it chugs along with little change. Sometimes there’s nothing wrong with keeping it simple.

11

And we’re back to the verse, with four bars of the rap with the same held synth note and snare variation. This is a good time to mention Robotnick’s production on the TB-303. Most records are mixed with the bass in the dead centre. This was done for a few reasons. In modern times, it’s because club sound systems tend to be mono—you could lose the bass if it’s pushed out to the side of the stereo spectrum. In the days of vinyl records, however, bass information in the side of the groove could actually knock the lathe’s cutting needle out of its track. However, Robotnick has treated his bass with what sounds like a stereo chorus. It’s yet another rule-breaking element and another clue as to why this song is so unique.

12

A return of the 8-bar chorus, with the same R&B-style sequenced licks between vocal lines. In the same Red Bull Academy interview, Robotnick stated that at the time he used a Korg synthesizer. While there is no definitive answer to what synthesizer he used, if we look at the time period, it’s quite possible he used a Korg Mono/Poly connected to an external sequencer and triggered by an 808.

13

The verse/chorus/verse structure continues. Here is a repeat of the four-bar verse. This album version appears to be an edit of the original 12” version with some remixing of the vocals. The album mix has quite a bit less ‘room’ sound on the rap.

14

And a return of the eight-bar chorus. This version of ‘Problèmes d’Amour’ is practically a masterclass in dance pop. Although there’s no mistaking that it’s dance music, it’s also very grounded in a traditional pop music structure.

15

The middle eight, again in B flat minor. We should note Robotnick’s 303 programming skills here. As anyone who has ever tried to program a 303 knows, it’s bloody hard, which is why many acid house records were programmed almost randomly. The fact that he’s been able to wrangle different melodically consistent basslines out of it (and in different keys) is pretty commendable.

16

Now here’s a surprise. Although this synth solo is in the original 12” version it was excised from the American remixes, likely because, well, it’s a little out of place. It has another key change, for one, this time to D major. There’s also the coronet-like synthesizer solo. This has a slight delay on it to give it a sense of space in this otherwise dry track, and is backed up by a polysynth playing a two-chord progression. Lastly, a brief snare fill ends this four-bar section.

17

Next is a short drum break. The rimshots drop out and the basic percussion line continues for two bars, with a backwards riser taking us into the next section. In the early ‘80s, risers were not particularly common. This one sounds like it was made by isolating the reverb tail from something like a snare and then reversing it. Of course, “reversing it” wasn’t all that easy in the early ‘80s, with the reverb tail being played backwards on one tape machine and recorded to another.

18

This is the last appearance of the chorus, which continues for the usual eight bars. Unique to this one, however, is a new, choppy guitar sound. There’s a distinct, post-punk feel to the playing. Robotnick played in Avida, an Italian new wave band, before making ‘Problèmes d’Amour’. Perhaps some of his post-punk roots are on display here. While this scratchy guitar might have sounded out of place throughout the song, appearing here at the end it adds an extra charge of interest.

19

Here is the final appearance of the middle-eight and its bizarre, Russian-inflected French. For this song, the Italian musician invented the character of Alexander Robotnick, a Russian immigrant singing in French. For Robotnick, both the lyrics and music were intended to be ironic. ‘But people really appreciated the bassline, and they said I started the electronic disco’, he said in the interview with Red Bull.

20

Finally, we have the outro. The 303 chorus bassline is accompanied by guitar, with a final appearance of the siren synth, this time soaked in lots of room reverb. The siren synth pans wildly around the stereo spectrum as the song fades out.