In our new book on techno production, we asked producers, “Who is your favorite producer of all time”? Nearly 70% said Jeff Mills. That tells you everything you need to know. So it’s about time we finally Deconstructed one of The Wizard’s most popular tunes to learn more about what makes him so unique.

You’d be hard-pressed to name a techno track more lauded than ‘The Bells’ by Jeff Mills. Released on his own Purpose Maker label in 1997, it’s been part of his DJ sets ever since and never fails to whip a crowd into a frenzy. He’s even recorded a version with a full classical orchestra, and despite the lofty setting, it still slaps just as hard with strings and brass as synthesizers.

‘The Bells’ is one of the most iconic techno tracks ever recorded yet it has an unusual, two-part arrangement. It’s also something of a contradiction. It’s minimal in arrangement, with never more than a few musical elements happening at a time, yet also maximalist in energy. It also has a rather unique structure, with the first half dominated by a musical motif and the second by the bassline. It’s a real puzzle box.

How did Mills do it? Let’s see if we can solve this puzzle.

The Arrangement

What’s Happening?

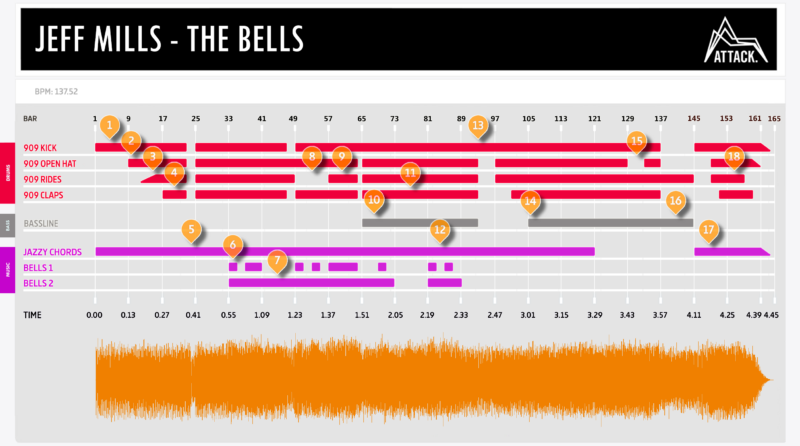

1

It starts, as so many other techno tracks do, with a kick drum. And what a kick it is. Firing out a straight four to the floor beat, it’s overdriven to all hell. This automatically injects a blast of energy into the track. The high tempo – 137.52 bpm to be exact – helps but really it’s the kick drum production that does all the heavy lifting. The TR-909 kick is distorted by cranking the mixing desk into the red. It’s also pushing air behind it, acting like a kind of reverb gate but here it’s likely a compressor exaggerating the noise floor of the mixer. What a sound.

The kick is paired with the song’s main musical element, a simple back and forth of notes that skips along incessantly in A minor throughout most of the song’s relatively brief run time.

2

After eight bars, Mills drops in a 909 open hat pattern slicing through on the offbeat. The decay on the hat envelope is full and open, allowing the hat sound to spill all over the beat. It’s also dirty and raw, a theme of the song. You can practically see the overload lights on the mixer pulsating red.

3

Just a hair after the introduction of the hats, Mills fades in the next percussive element, 909 rides slashing in an 1/8-note pattern. By fading them in rather than changing patterns on the drum machine or even unmuting the mixer channel, Mills allows us to to hear him performing the song in real time. This gives it a live feel and contributes to the track’s powerful surge of energy. The rides are open and ringing, splashing across the sound field like a swollen waterfall.

4

The next element to arrive, 909 claps, skip in at bar 17. These are run through a delay for added rhythmic power and yet also pushed back in the mix. As more elements are introduced later, they’ll become difficult to hear but will be contributing to the energy nonetheless. Not everything in a song needs to be clear and loud. Subtle sounds have their place too.

5

At the end of the eight-bar section between positions 17 and 25, Mills drops out all of the elements except the notes, letting us hear them well for the first time. Mills is a big fan of dissonance and you can hear it at play here. Though a simple back and forth, it nonetheless creates a sense of tension, stretched even tighter by the coming melody.

6

After eight bars of letting the song’s elements – kick, hats, ride, claps and notes – ride along unchanged, Mills drops the melody, the bells of the title. There are two layers, a lower synth sound with a slightly longer decay, and a shorter, higher one. The high sound plays consistently while Mills brings the lower one in and out almost at random. Sometimes it’s for two bars, sometimes for four. He’s working the mixer, performing it like an instrument and riding the energy.

7

Now at position 41, Mills drops the lower bell and lets the higher register roll for eight bars. For the final two bar section, he drops out the kick and claps. With the massive kick briefly silenced, the remaining sounds jump out of the speakers like light in the dark escaping from an opened box. Notice how there are no programmed drum fills or sequence changes in ‘The Bells’. All energy is directed by muting and unmuting looping patterns.

8

Mills is staying with the melodic bell section, again alternating between the low and high. This back and forth, and the insistent, repetitive nature of the melodic line, creates a real sense of urgency. Hearing it performed live with a classical orchestra places it in a different context. Although there’s a beat, it’s mixed lower than in the studio version, highlighting the classical instruments. Heard in this context, the parallel between techno and modern classical like 20th century minimal becomes strikingly clear. There’s very little difference between artists like Jeff Mills and composers such as Steve Reich and Philip Glass, save the building where their songs are played.

Back to the track, he’s now muted the chaotic rides to bring the energy down a touch. The claps are back as well, contributing to the percussive groove.

9

The rides don’t stay away for long. At bar 57 they smash back in, now pitched lower than before. Mills quickly corrects this, the unnaturalness of the pitch change contributing to the almost punk-like energy of the track. The lower bell is now running free as well. After seven bars, Mills gives the hats, rides and claps a one-bar break.

10

Here at bar 65, almost a full two minutes into the 4:40 run time, Mills introduces the bassline. He drops out the lower bell pattern and fades in the bassline, a 16th-note affair with a chuffy attack portion that pulls double duty as a high-hat line.

11

After a a brief, two-bar exposure of the lower bell line and four bars of the high bell, Mills gives the bassline the spotlight for eight bars. All of the percussive elements and chords are along for the ride as well.

12

From positions 81 to 89, we get a final eight bars of the main bell motif, alternated in the style that we’ve become comfortable with. And then, surprisingly, we never get to hear it again. The bassline and all the elements save the bells continue for four more bars.

13

‘The Bells’ is too linear, too jacked up to bother with long breakdowns and build ups but it does give us a quick middle section to catch our breath. At position 93, we get four short bars of just kick and notes. Then it all slams back in save the claps, which come through the door four bars later at position 101.

14

We’re now in the back half of the song, which is devoted to the bassline. This is an odd structure for a dance song. Most tracks have a single theme and they ride it hard throughout, varying it in some degree but rarely straying from it. ‘The Bells’, however, has two movements, with the first part highlighting the melody and the second part hammering the bass. This kind of arrangement makes more sense when you consider how techno was DJed in the 90s. If you’re playing one song at a time, singular motifs work fine. But if you’re layering songs with three or more decks, you’re going to want tracks that are constantly changing and sound good when overlapping. Mills played ‘The Bells’ out live for two full years before releasing it. It’s not a stretch to imagine him composing it this way for his sets. He is The Wizard, after all, and has long been famous for DJing with three turntables.

15

At position 121, Mills kills the notes, one of the few places in the song where he does. This is to let the bassline, which he slowly modulates, run free. The bassline recalls Giorgio Moroder’s famous one from Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’, minus the progression. Mills lets his run on its own for 16 bars, killing the rides for two bars at 129 and then bringing them back.

16

We can hear the bassline in all its power for four bars from position 137, when he cuts everything except the rides.

17

Now the chords come back, returning us to the main theme of the track. The kick also slams back in.

18

For the remainder of the song, Mills brings in and then out the main percussive elements of rides, open hats and claps, letting the kick and chords stay strong until fading the whole thing out.

If you like this article, you may enjoy reading:

This article is an excerpt from our new book, The Secrets of Techno Production, which is out now on the Attack Store.

This comprehensive 218-page book offers exclusive content from Attack’s award-winning team, covering everything you need to produce all forms of techno. Plus, it includes over 1GB of audio samples and additional project files, making it an essential resource for both beginners and experienced producers.

Featuring artist insights from 99999999, Alan Fitzpatrick, Cressida, Dave Clarke, Deepak Sharma, DVS1, Florian Meindl, Francois X, Helena Hauff, Hemka, Indira Paganotto, Jamaica Suk, Ken Ishii, Len Faki, Lucinee, Manni Dee, Metapattern, Minuit Machine, Nina Kraviz, Noemi Black, Par Grindvik, Perc, Pfriter, Raven, Regal, Risa Taniguchi, Rudosa and more!

09.06 AM

Jeff Mills has always been my favorite DJ off all time, go Jeff we love so much.