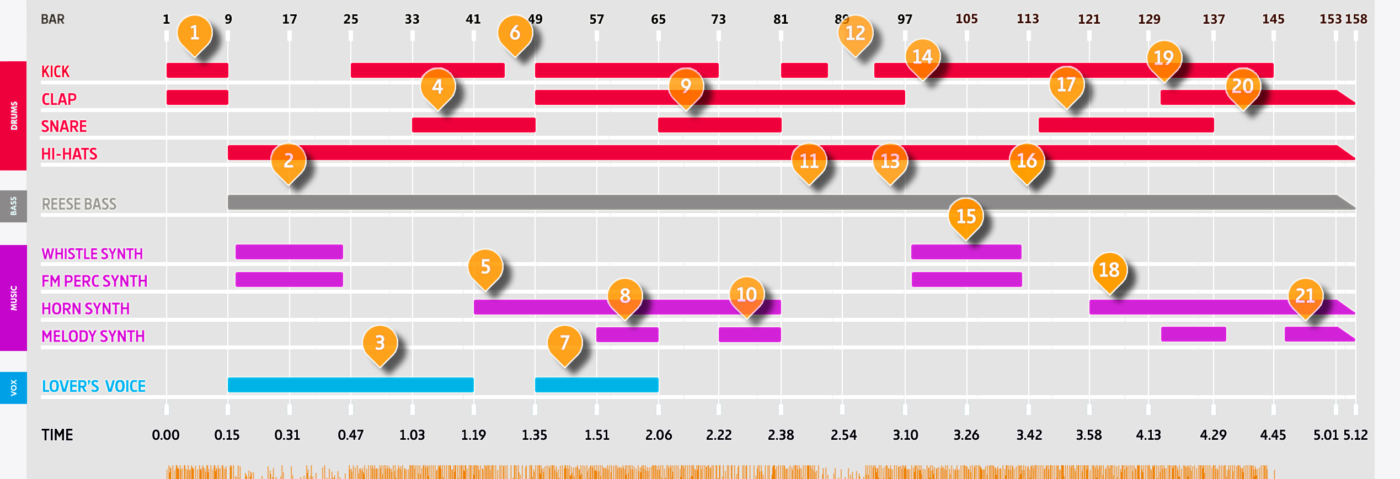

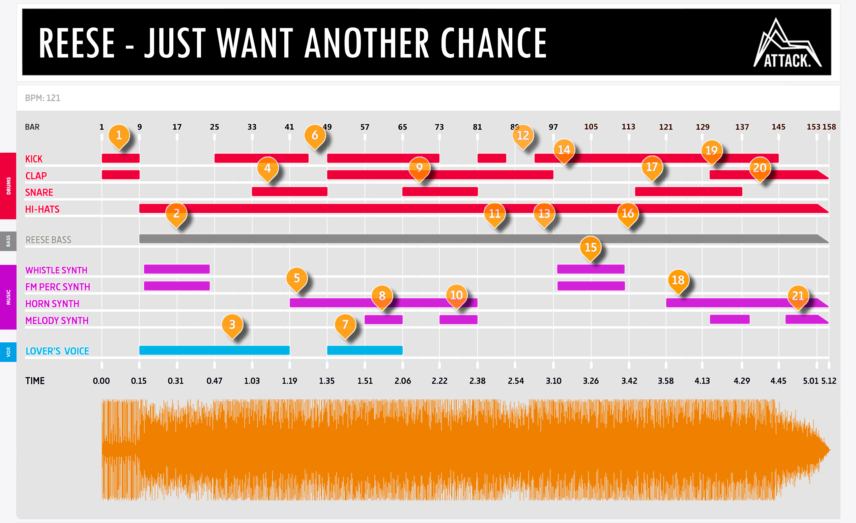

Deconstructed is an ongoing series where we take apart the arrangement of a song to see what makes it work. This time, we’re looking at Kevin Saunderson’s Detroit techno classic, ‘Just Want Another Chance’.

For readers of Attack, Kevin Saunderson likely needs no introduction. Along with school mates Juan Atkins and Derrick May, and collectively known as the Belleville Three, Saunderson helped establish the sound of Detroit techno.

Although perhaps most widely known for his bright, vocal-driven work with Inner City, Saunderson is just as comfortable working with darker colours. Originally released in 1988 under the Reese moniker, ‘Just Want Another Chance’ is a sparse and heavy track. Originally a native of New York, Saunderson often returned there as a teenager, where he would attend the Paradise Garage and hear Larry Levan in action. It was these visits to the Garage that inspired him to make the moody ‘Just Want Another Chance’.

While there’s no denying its classic status, what is it that makes this song so iconic? Of course, there’s the well-known bass, which we’ll cover in detail shortly. But the arrangement is also pretty special. Let’s break it down and see exactly what’s happening.

The Track

The Arrangement

What’s Happening

1

The 121bpm song starts with eight bars of kick and clap. Saunderson is using a Roland TR-909 for the rhythm track, and pretty much every sound used has been treated in some way. The 909 had separate outs for each channel, making it easy to route them through effects before sending them on to the mixer. The kick has a short, gated reverb on it. It also sounds like it’s overloading, likely by pushing the gain on the mixer. The claps are also treated with gated reverb, these longer and with a light flange on them to create a sense of movement. Although gated reverb was a staple of ‘80s production, it’s most associated with big snares. By instead placing it on the kick and clap, Saunderson has instantly created a dark, oppressive mood.

Saunderson worked on establishing himself as a DJ before turning to production, and that’s evident in this DJ-friendly, percussion-only introduction (short though it is). Note how Saunderson drops out the kick before the turnaround, letting us (and the DJ) know that a change is coming.

2

There’s a lot to unpack in this 16-bar section: drums, vocals, melody, and that bass, so let’s address them one by one.

In an abrupt shift, the gated percussion of part one has changed to closed and open hi hats, playing a lightly swung pattern, with the open hats playing irregularly on the offbeat. The closed hats are centred in the mix, while the open hats are panned slightly to the right. Delayed open hats fill out the soundstage by appearing on the left.

Next, the vocals. Saunderson himself supplies the whispered vocal track, imploring an unnamed lover to come back to him. The vocals are peppered sparsely throughout the section and add to the 4 am, late-night vibe.

There are two synthesizer melodic phrases in this section that trade-off in a kind of call and response. The first is a whistle-like sound with filter modulation that speeds up or slows down according to the note played. The second is a hard, slightly inharmonic FM percussion sound doing a climbing, three-note pattern. Both melodic lines sound relatively unquantised, giving the song a loose, human feel.

Lastly, there’s the bass. Or actually, firstly, there was the bass. In a 2018 interview with the Red Bull Music Academy, Saunderson explained that he made the sound with a Casio CZ-1000, and that the patch itself inspired the direction the song took. “You know when I was creating that bass, I was thinking dark, deep, I was thinking Paradise Garage”, he said. “So I just got into the parameters which I always enjoyed doing because sometimes when you’re creating sounds, it can inspire you to play a certain way or you hear something that inspires you to play something on top of that”.

3

In this four-bar section, the melody cuts out, leaving the whispered, intimate vocals alone with the deep, rumbling bass.

The kick has returned as well, joining the hats and giving the song momentum. Finally, a snare from Saunderson’s TR-909 hits, indicating that the next section is starting.

4

As Saunderson continues to plead, “Don’t give up”, the snare strikes on every backbeat, with an additional hit at the end of every four-bar section. The snare is treated with a bright reverb, giving it some space in the mix and setting it apart from the bass and remainder of the percussion.

‘Just Want Another Chance’ is a very sparse track, often little more than vocals, bass, and percussion. By mixing the percussion with three different effects—gated reverb on the kick and clap, delay on the hats, and reverb on the snare—Saunderson creates a unique vibe. Normally, we think of a drum kit as existing in a single space, with every piece of percussion sitting in the mix in the same way. By varying these spacial relationships, Saunderson has created a confused, unreal space, perfect for the woozy, late-night vibe of the song.

5

‘Just Want Another Chance’ was written in the key of Bb minor. With its five flat notes, this key is usually associated with gloom and darkness. Fittingly, much of the song is rather dark. However, it’s not all cobwebs and shadowy corners, as the melody that starts on bar 41 shows. A simple motif, it’s built around a repeating four-note line. The sound, like a truncated horn, is dry, aside from some slight modulation, and pushed low in the mix.

6

Here the kicks drop out, giving the melody a chance to take centre stage, if just for eight bars. Although he’s best known for helping birth Detroit techno, Saunderson is very much a fan of disco and melody. He has attributed this to his New York upbringing. You can hear it in his Inner City project and to a lesser extent, here. Even though this is a very dark song, with long passages with little to no melody, it still has a distinct, melodic flavour.

7

At bar 49, the snare disappears and is replaced by the gated claps that we first heard in the intro section. Saunderson’s plaintive vocals also return here, intoning, “I want you, I love you”.

8

As the vocals continue, the synth melody is joined by a higher counterpoint melody. This sounds like it could even be the same synth, playing one octave higher. The bright, high notes provide a contrast to the unrelenting (and unrelentingly dark) bassline.

9

At bar 65, the counterpoint drops out, replaced by the 909 snare. The vocals take a breather as well. There’s an almost dub reggae-like use of space in this song, albeit without the usual dub-style effects. It’s no wonder early ‘90s jungle producers were attracted to this song.

10

Here the counterpoint returns for another sixteen bars. Notice that the kicks have dropped out. This steers our focus to the melody.

11

At bar 81, both the snare and counterpoint are silenced, giving the infamous bass a chance to do its thing. The Reese bass, as it’s come to be known, has taken on a life of its own. Originally sampled by drum and bass producers in the early ‘90s, it’s now mutated and evolved into a massive monster. The irony is the bass sound is likely much better known than the actual song. Saunderson is very much aware of the sound as well, having been in London when the sound was first gaining popularity in drum and bass circles. “Hey, they didn’t create it”, he said of the Reese bass in the same Red Bull Music Academy interview, “but they was able to grab it and use it creatively”.

12

At bar 87, the kicks drop out, leaving just the hats, gated claps, and deep bass to roll along for 12 bars. While we mentioned earlier that the bass was made with the CZ-1000, we should point out that Saunderson has stated in other interviews that it was the CZ-5000, and not the 1000, that provided the original tone. Further clouding the issue, he’s on record saying that he owned both (or possibly even a CZ-2000, although none has ever existed). However, both the 1000 and 5000 have the same synthesis engine so it really could have been either one.

13

After those 12 bars, the kick comes back in. The bass continues, playing that same, insistent pattern. This song is indeed very deep, and very dark.

14

At bar 97, we lose the gated claps, leaving just the kick, hats, and bass to chug along for two bars. Imagine being a punter on the dancefloor in 1988, listening to this in a hot, sweaty basement club. By this time there were a lot of revolutionary things happening in the dance music world, but was there anything as heavy and moody as ‘Just Want Another Chance’? Minds, as they say, were almost certainly blown.

15

At bar 99, the whistling synth and FM line make their return. They play the same melodies as at the beginning of the song, this time only for eight bars. The whistling synth then continues for another eight bars, this time without its FM counterpart present. Although it avoids the signposts of the genre, again, Saunderson again employs that dub-like use of space, particularly in the restrained use of melody.

16

At bar 111, we’re back to eight bars of just the kick, hats and bass. But with a bass this massive, though it may be minimal, it’s never lacking.

17

We’re deep into the song now. The snare makes a return, and continues with the same pattern as before, this time for 16 bars. Notice how there are no fills in this track. Saunderson is not interested in building up energy. It’s too late at night for that kind of peak energy. This is for the all-nighters, sliding through the dark recesses of a sweaty basement club.

18

At bar 123, the horn melody returns, rather abruptly. It almost sounds as if Saunderson is punching it in manually. It could be that all of the various elements of the track are looping endlessly, with him muting and unmuting parts on the mixer as he goes.

19

As before, the horn synth is next joined by the same counterpoint melody. The claps, playing the same pattern, begin at the same time.

20

After 16 bars, the counterpoint retreats, leaving the main melody to continue. The snare falls away as well. We’re clearly heading towards the end of the song.

21

At bar 145, the kick is silenced. In modern dance tracks, turnarounds generally happen at the end of patterns divisible by four (four, eight, sixteen, etc.). Here though, Saunderson has stopped the kick after 14 bars from the start of this section. An unusual choice, especially for a record made to be played in clubs.

22

Two bars later, at position 147, the counterpoint melody returns. This section continues for sixteen bars, while the song fades out. Yes, fades out. Although fade-outs are extremely rare in modern dance songs, producers did sometimes still use them during this era.

23

At bar 155, the counterpoint again disappears, leaving the horn melody, bass, claps, and hats to continue until complete fade out.