In this latest Passing Notes article, we take a better look at Todd Terje’s evergreen “Preben Goes to Acapulco”. Taken from the 2014 album originally named “It’s Album Time”, the tasteful Norwegian producer uses advanced arpeggio techniques to accompany a modulating chord progression.

There’s so much to admire about Todd Terje’s “Preben Goes to Acapulco” that it was hard for us to choose which sections to look at. Where do you begin when a track, and indeed a whole album, oozes so much sultry, sexy and pimptastic swag showcasing Terje’s total grasp on “80’s Nordic / Miami” vibes.

Despite the struggles of pinning down a section to cover, we eventually settled on the intro chord sequence which accompanies the signature arpeggios floating effortlessly above. How and why does it sound so good? What sorcery is this? Let’s set the time machine to 2014 via 1984, head to Miami (via Oslo) and find out!

Top tip: For further listening we recommend Bawrut’s “Pronto Arpeggio”, Frankie Knuckles’ “Your Love” or Daft Punk’s “Aerodynamic’. For something completely ridiculous and not at all dance music, why not check out Yngwie Malmsteen’s ‘Arpeggios From Hell”. Just for the name alone, it’s worth it.

The chord progression

Anyhow, returning to heaven…here’s the full sequence we’re looking at today:

Audio PlayerLike anything, grounding ourselves in the fundamentals is imperative. So to kick things off, let’s turn our attention to the sonic glue: the chord progression. By familiarising ourselves with, and getting a handle on what Terje is doing, we’ll be better placed to piece together the whole arrangement later.

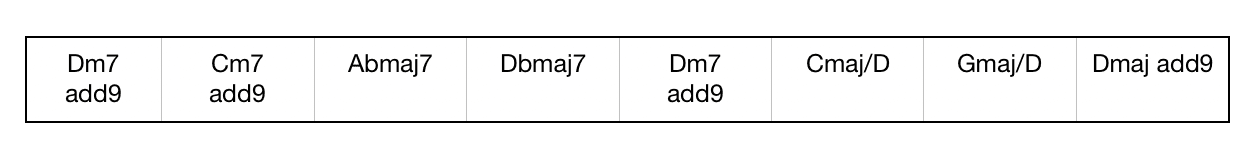

This fourteen bar chord progression, running from 0.20-0.55 seconds, is played as follows:

Each chord is played for two bars except chords five and six, Dm7add9 and Cmaj/D, which are each played for one bar. What’s obvious is the modulating sequence. Beginning in the key of D minor, by the end of the sequence the key has modulated four times! Let’s break it down.

When Terje goes from Dm7 > Cm7 the key changes to C minor. This is clear as typically a song in the key of D minor, there would be a C major chord and not a C minor chord. The following chord, Abmaj7, is also a chord from the key of C minor so we are firmly in C minor at this point. This is the first modulation away from D minor.

Continuing the sequence, at the next chord change (Abmaj7 > Dbmaj7 ) we’ve changed key again. Dbmaj7 is not a chord from the C minor family and Terje is using Abmaj7 as a pivot chord to jump from the key of C minor to Db major.

Top tip: This method of using a transition or moving chord, a chord shared by the home and destination keys which acts as a pivot linking the two keys and allowing for a smooth transition, is also known as diatonic common chord modulation. It’s one of the most common techniques for modulation. In our case the Abmaj7 is shared between the keys of C minor and Db major so that’s our transition chord.

Following the Dbmaj7 chord, he moves up a semitone thus returning to our original key of D minor. He then follows this with a Cmaj/D (a slash chord) but as all the notes of the Cmaj triad are found in the key of D natural minor, there’s no modulation here.

For the last two chords, Terje transitions to the key of D Major. When the sequence plays Gmaj/D (this means playing a C major triad over a D bass note, a type of chord known as a slash chord) the G major triad contains B, which is not part of the D minor family. All of the other notes he plays in this chord are in the D minor family. The addition of one new note makes the modulation subtle…but it’s there. Finally, the section ends with a resolution to D major.

Here is a recreation of the whole section without the arpeggios:

Audio PlayerAs you’ll have noticed, the progression sounds empty without the arpeggios delicately flying above. It also has a distinct classical arrangement as the Dulcimer is mostly playing triads – a common chord voicing when composing classical music. Arpeggios are often used in classical music to give chords movement – and you can hear why as without them you remove all that modern synth swag.

Here’s the chord progression:

Instruments and intervals

The main contributors to the musical fabric are:

- A synth bass holding the root notes

- A Dulcimer playing triad chords

- The 32nd-note synth arpeggios

Emulating the very unique sound of a dulcimer, and reverse engineering it in a digital environment can be tricky! Such a large chunk of its sound comes from articulation and how the strings are plucked (which is either by being hit with two hammers or a stick) that we’ve therefore loaded an instance of Santur’s free Hammer Dulcimer Instrument. We recommend it as a good starting point before splashing cash on something more extensive like Emberton’s Mountain.

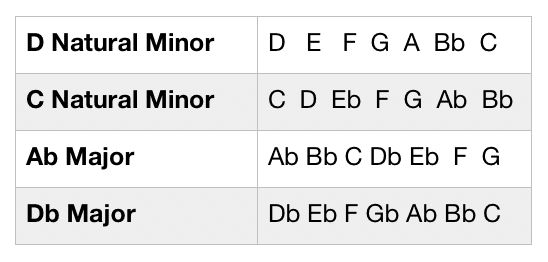

As we’ve established, there is a lot of modulation to wrap your production paws around. It is therefore a good idea to look at each chord as its own scale or “chord scale” as it helps breakdown what we are playing with. This section’s first four chords and their own scales are shown below:

Top Tip: A major scale is one in which the third scale degree is a major third interval above the tonic note, while the third scale degree in a minor scale is a minor third interval above the tonic note.

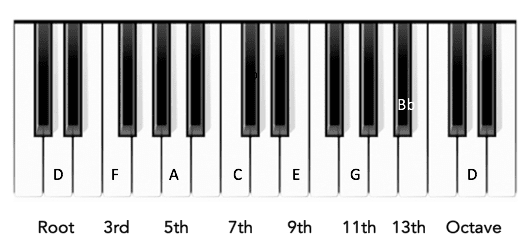

Looking at this, a C is the 7th note in a Dm chord but also the 3rd note in an Ab major chord scale. Remember that when referring to chord scales, intervals are referred to in this order: Root, 9th, 3rd, 11th, 5th, 13th, 7th, Octave. Below is an example of a D minor chord’s intervals:

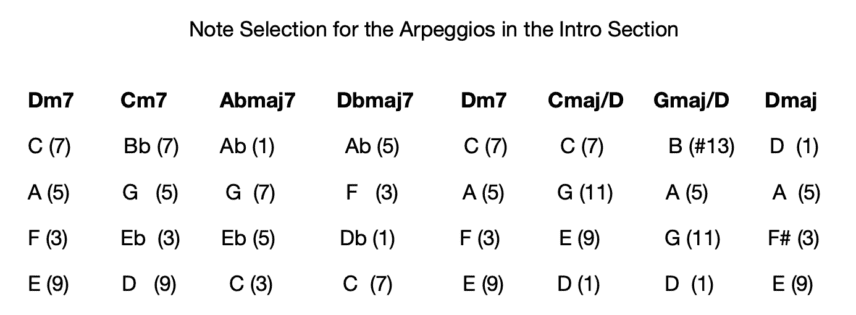

With all this in mind, let’s take a look at Terje’s arp note selection and the intervals of each note in relation to it’s chord scale. We’ve shown this in brackets below:

There are two advanced compositional techniques at play. The first is using more uncommon intervals or colour notes like 7ths, 9ths and 11ths. These give the sound a sense of wonder and contrast against the classical triad-based chords played by the supporting dulcimer.

The second is the changing order of the arpeggio note intervals with every chord to keep the arpeggios cohesive. For example, as you can see in the table above, the first two chords’ arpeggios go 9-3-5-7 but then the third goes 3-5-7-1, the fourth goes 7-1-3-5, and it continues to change with every chord after that. It’s highly personalised.

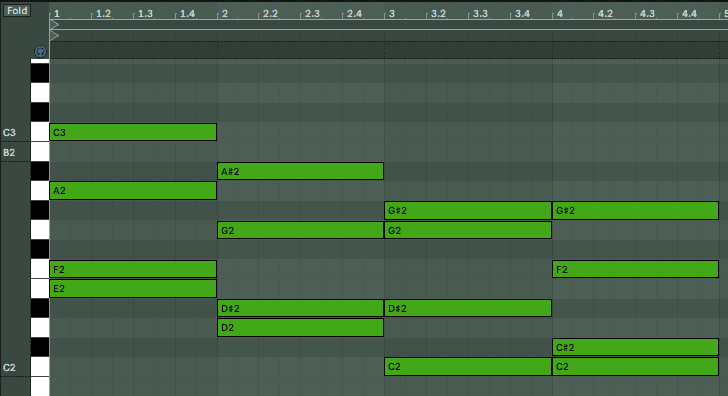

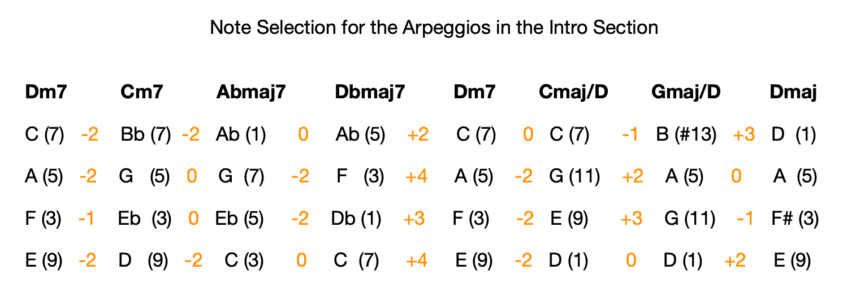

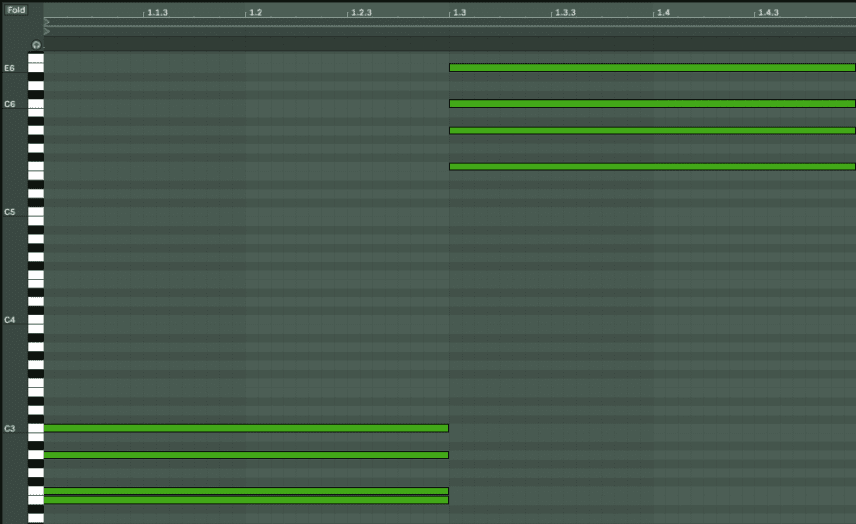

Why does this sound good? Well, these chords would be fairly straightforward to play by a keyboard player in a sequence without too much hand movement. Just as a compressor keeps an audio signal steady and consistent to help it find its place in a mix, this technique keeps arpeggios steady and prevents them from jumping around too much across the piano roll. As you can see in the piano roll below, all of the notes are similarly placed helping keep things nice and smooth.

To emphasise this point further here is another version of the above piano roll that indicates the movement, in semitones, of each note as the chords change. You’ll notice that there is rarely movement of more than two semitones.

Making the Arpeggios in Live

Let’s now look at how we can recreate the arpeggios.

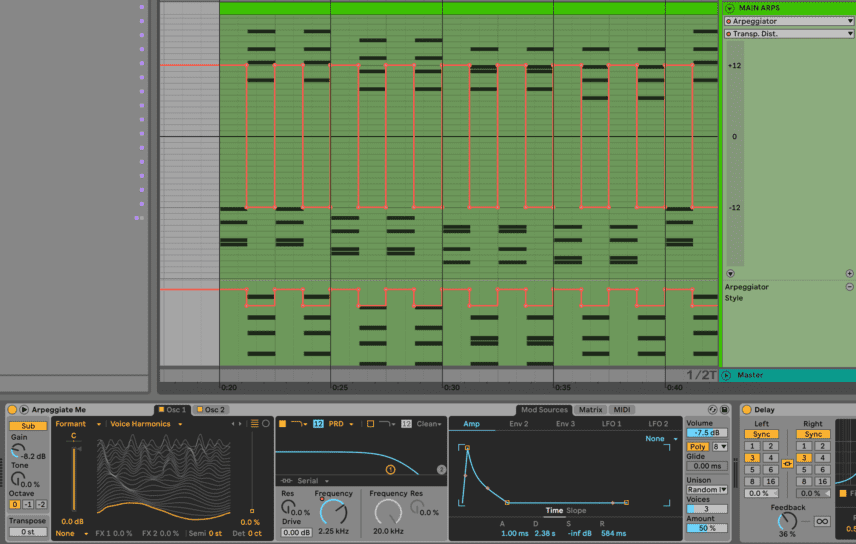

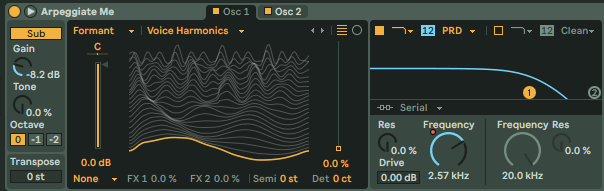

Set the BPM to 96 and load Live’s Wavetable and find the preset “Arpeggiate Me”. Lower the cutoff to around 1.8 kHz.

Top tip: For more arpeggio-related production techniques check out our “Introduction to Arpeggiators” and “Complex Arps” articles from the archives.

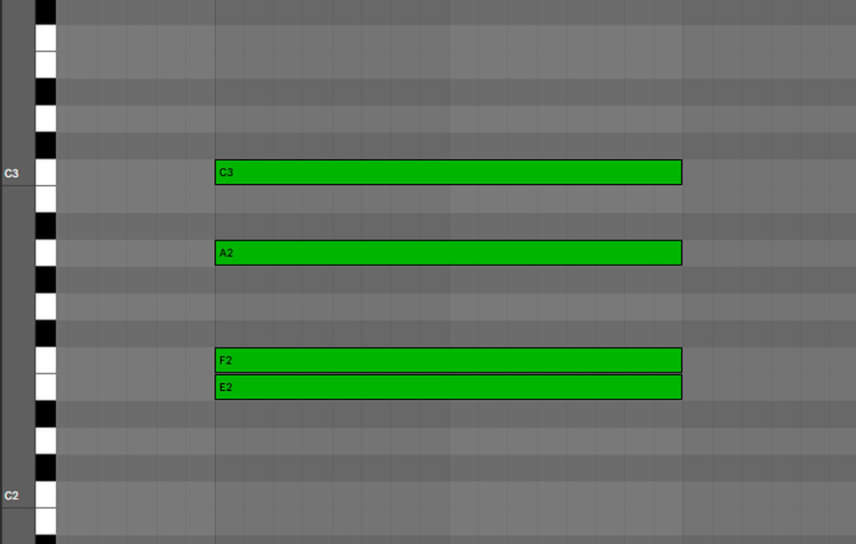

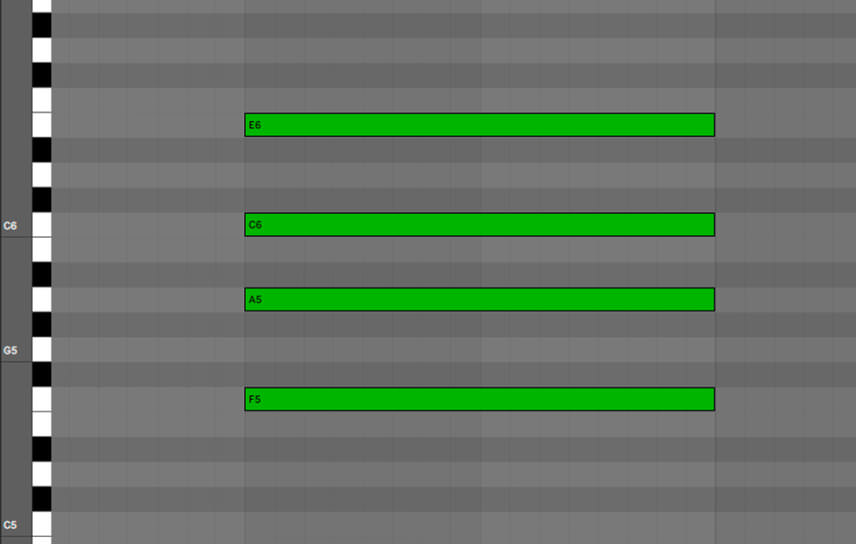

Now load Live’s Arpeggiator MIDI-Effect, create a new MIDI region and draw in the first chord, extending the notes for half a bar. For example the first chord Dm7 is drawn as shown:

Then, for the second half of the bar, draw in the same chord three octaves above but with the lowest note an octave higher. We’re doing this as in subsequent steps we’re going to set the arpeggiator to make the notes descend for the second half of the bar.

The piano roll for one bar should now look like this:

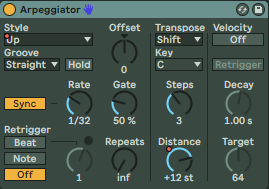

Make sure that Style is set to “Up,” the Rate is 1/32 and the Steps set to 3 (the pattern will move up three octaves during the sequence).

Since we want the same notes to descend three octaves and starting at the 3rd beat of the bar we have to automate the pattern to change from “Up” to “Down” at this exact point. We also must automate the distance parameter to -12 st instead of +12 st so that the arpeggiator understands to descend each step in octaves.

Top tip: remember that while in Live’s automation mode you can select automation envelopes, copy them and paste them to the next bar with command + D (mac) / ctrl + D (windows).

As we automated the style to “Down” and even though we inverted the chord in the upper octave by moving the E an octave up, the E is still the first note that is played on the way down. This same trick is used in every bar of this track – I.E the lowest note of the arp chord is moved to the higher octave for the descending second half of the bar.

One of the most important aspects of Terje’s arps is that they seem to be coming and going, almost getting louder as the arps go up and then disappearing as they descend. This is achieved by automating the filter cutoff frequency so that it opens up until the arps reach their highest note (exactly at the half-bar point) and then gradually closes until the lowest note is reached.

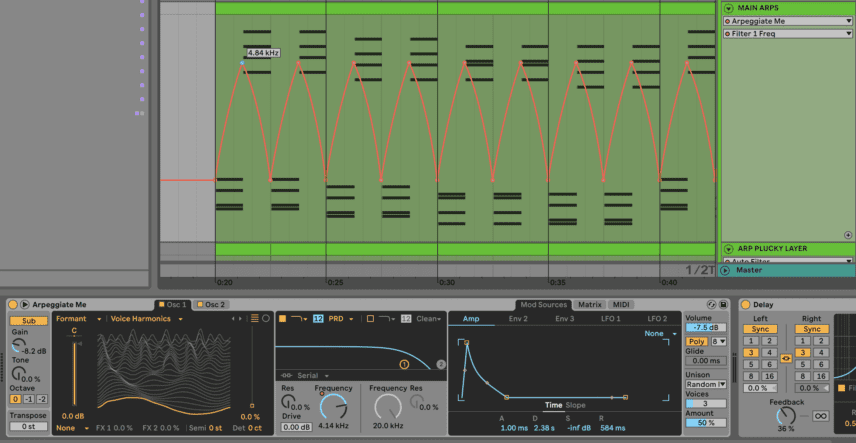

In this example we set the cutoff at 129 Hz and then open up until 4.84 kHz at the peak, and then closes again to reach 129 Hz exactly at the first beat of the next bar:

As Terje would appear to have his Res at 0, we too can keep the resonance parameter at 0 for a clean sweep up and down. This is a creative decision as boosting resonance can completely change the character of your arps. For example, check it out – in this example we’ve set the Res to 60%:

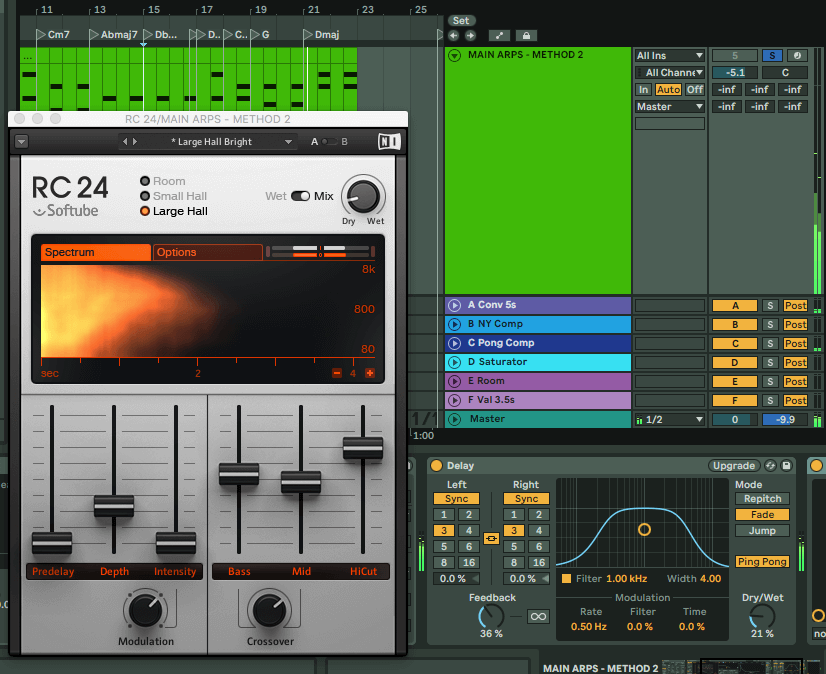

Audio PlayerNow, add a slight reverb and delay to your taste but try ensure the effects don’t wash out the notes or add too much overlap.

Finally, you can duplicate the channel and then replace the instrument of the second channel to layer the arpeggios with a different sound. For example, we can add a pluckier synth as a layer to give the arp more of a sharp transient. In the below audio first you will hear the arp with the layer and then without the layer:

Audio PlayerFinally, piecing it all together and it should sound like:

Audio Player