11 & 13 Chords

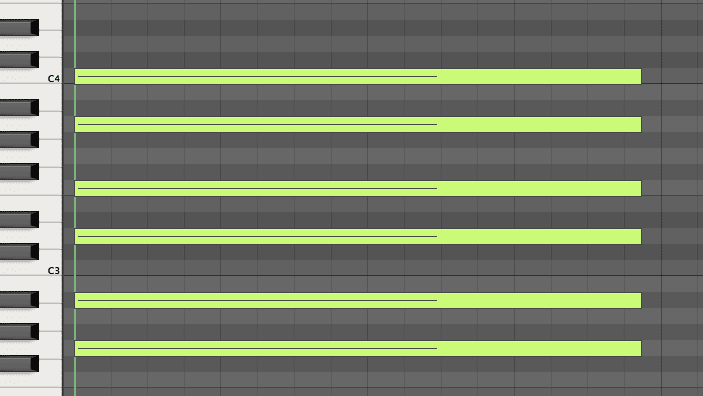

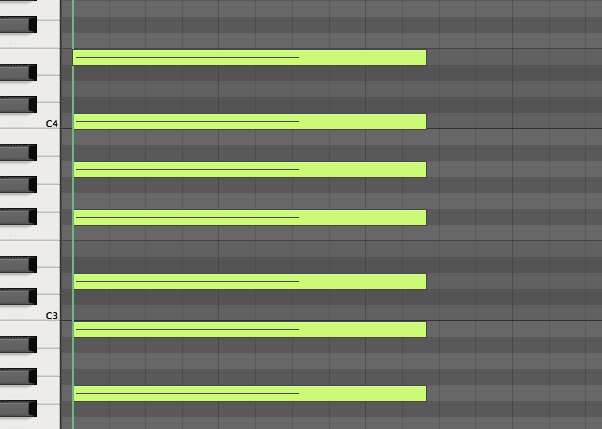

The same logic can be applied to fourth or sixth notes of the scale, playing them in the higher octave in order to create 11 and 13 chords. They sound progressively richer and fuller as more of the intervals are added. Here’s a G minor 11:

And a G major 13, voiced as shown below:

So far we’ve stuck to intervals which fit neatly into the major and minor scales, but what happens if we break out of those intervals and include other notes? Let’s take a look…

Dominant Chords

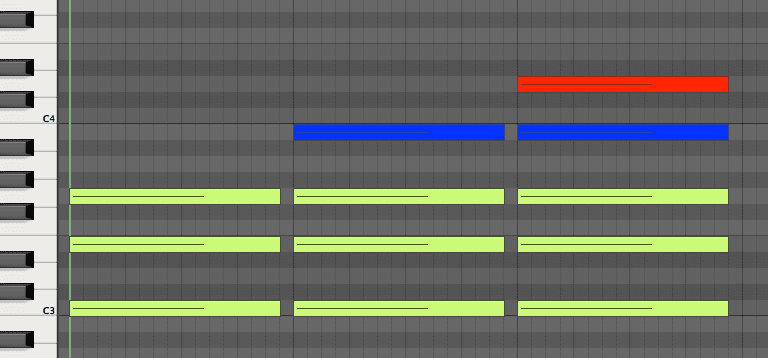

The fifth chord of every scale is said to be the ‘dominant’ chord. For instance, if your track is in the key of C major, the dominant chord is G major. The G ‘dominant 7’ chord (notated ‘G7’) is voiced as below – a major triad, but with the minor 7th (F, highlighted in red) rather than the major 7th (which would be the F#, a semitone up):

It has an instantly recognisable bluesy character.

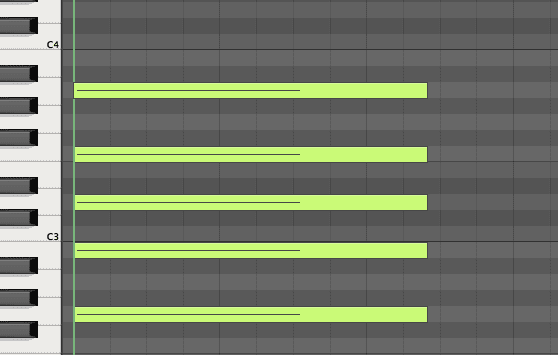

We can apply the same principles from earlier in order to create further variations on these dominant chords. A dominant 9 chord, for instance, consists of the root, major 3rd, 5th, minor 7th and 9th. In the case of G, that’s G, B, D, F, A:

A great example of a dominant 7 chord can be found in the Prodigy’s ‘Everybody In The Place’, during the sample that comes in 32 seconds into the track:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UKmhlA2S2KU

12.29 PM

Great, thank you, these are my favorite posts on here!

03.10 PM

Love these theory related posts, thank-you. Would be great to hear about changing keys within songs and cadences, that stuff always baffles me.

08.25 PM

change key to the 5th in the original key is easiest like C major to G major

02.04 PM

Google ‘Pivot chords’ Andy, that should help.

11.09 PM

Which piano are they using here? Is there a good free plugin for Ableton?

05.54 PM

I love posts like this that put theory in plain English and include many musical snippets. Thank you thank you!