With examples from Inner City, Daft Punk, Andrés, Skrillex and MK, Bruce Aisher examines five contrasting approaches and demonstrates how these aesthetic choices define the sonic fingerprint of the music.

When it comes to mixing, the proclamation to use your ears is well worn – and largely accurate. However, that platitude can easily obscure the fact that there are trends, conventions and aesthetic decisions involved in that process.

In this feature we’ll analyse the mixes of five contrasting tracks, demonstrating how their approaches differ. We’re focusing on two key aspects here: the use of the frequency range and the use of the dynamic range. Of course, there are countless other variables which determine the sound of a mix – use of the stereo field, ambience, noise and distortion, and so on – but, as we’ll see, these two key factors can tell us a lot about any mix.

Our tracks span 25 years and a range of genres, using a range of different instrumentation. When compared, they should provide some interesting insights into the way mixdowns have evolved over the years.

‘Good Life’

A good place to start with any audio analysis is to look at the track as whole. To begin, let’s go all the way back to 1988 and one of the defining tracks of modern electronic dance music.

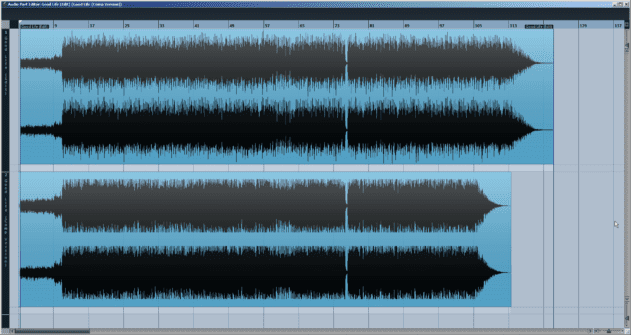

Here, the original version of Inner City’s timeless classic ‘Good Life’ is compared to a version of the same track taken from a more recent compilation album. For reference, here’s the original:

The first thing to notice is that the version taken from the compilation album (the lower of the two waveforms) is shorter. The structure of the track is otherwise identical – either the need to squeeze more tracks on to the album meant adding an early fade, or the compilers assumed that modern listeners weren’t interested in the extended outro.

More importantly, the original is far more unruly in terms of signal level. Even at this resolution it’s clear that the edited version on the compilation has undergone some dynamic processing. In this case it looks like limiting during the mastering process is the culprit. This gives the waveform display of the compilation version a noticeable flatness across the signal. This fast-acting, high ratio dynamic compression has the effect of bringing up the average level. This is ultimately perceived as greater loudness. The compilation version has probably been compressed or limited in order to keep up with the ‘loudness war’

of the last couple of decades.

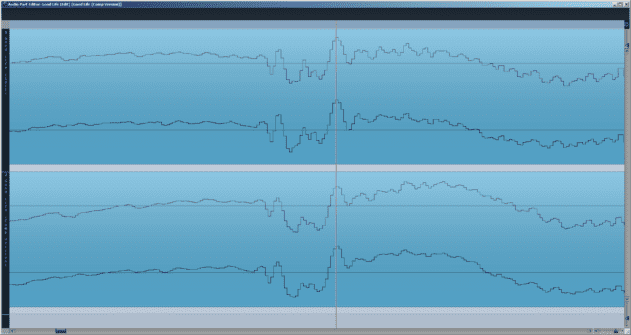

Intriguingly, the peak level of the second version is lower than the first (approximately -2 dB). We can see this more clearly by zooming in:

This difference was perhaps due to level adjustment between tracks at the compilation stage, though the ultimate cause is difficult to pinpoint without speaking to those in question.

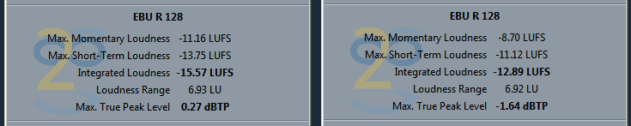

This difference in perceived loudness is borne out by the stats. Here we’ve run both tracks through an EBU R128 analysis (the European Broadcasting Union’s recommended loudness and level standard – see here

):

The original (on the left) has a lower Integrated Loudness (the average loudness over the whole track) despite the larger peaks.

Notice also the different maximum True Peak levels. This is measured using an algorithm to calculate potential inter-sample peaks that can cause distortion in the digital to analogue conversion stage. This may appear counterintuitive, but this ‘peak beyond 0 dBFS’ issue is something that may arise during mixing, mastering and format conversion (WAV to MP3 etc).

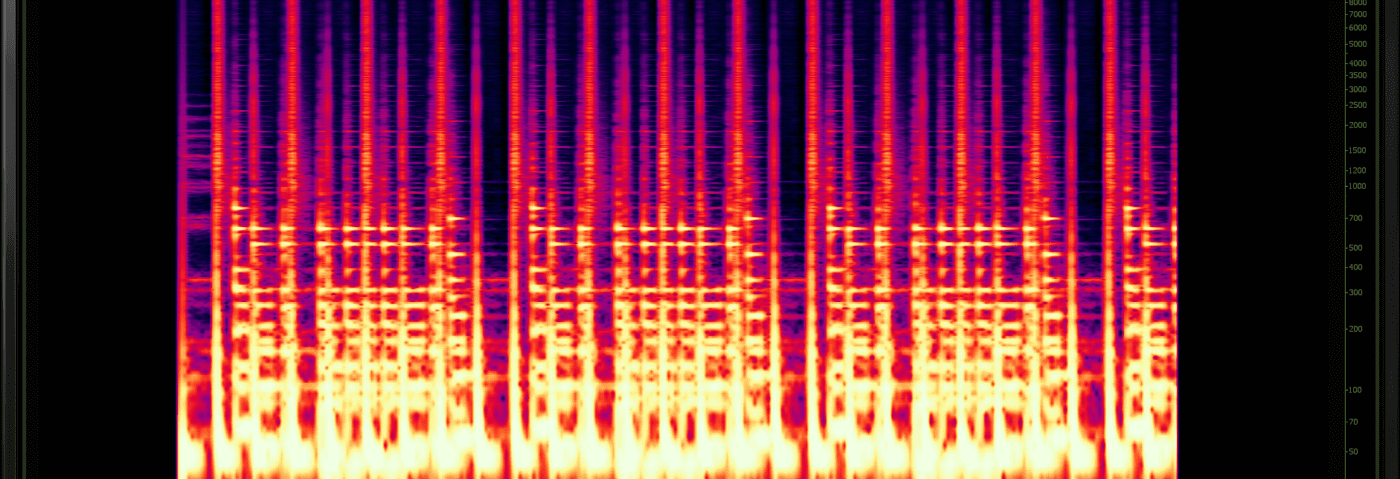

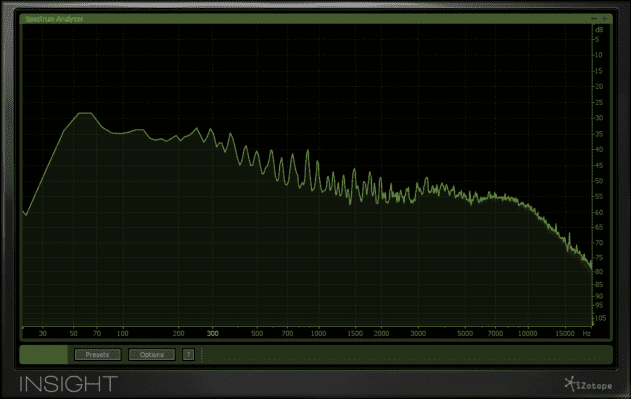

Something that was noticeable when listening to both versions is the comparative brightness of the original. This is the frequency plot of the original:

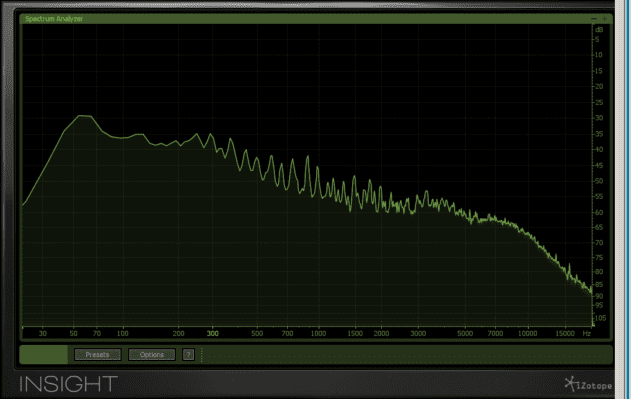

And this is the ‘compilation’ version after being adjusted to match the low-frequency level of the first:

Look closely and you’ll notice that there is level difference of over 5 dB at 5 kHz, and at 15 kHz it’s more than 10 dB. Despite this, the overall shape of both is what we might expect, with a gentle rolling off in level moving from low to high frequencies. This will often dip more dramatically from 10-20 kHz.

What conclusions can we draw from this analysis? First of all, it’s important to bear in mind that Kevin Saunderson was aiming for clean, clear production with his Inner City tracks of the late 80s. It’s often lazily assumed that all late-80s dance production was amateurish – terms like ‘lo-fi’, ‘rough’ and ‘dirty’ are thrown around – but the truth is that the mix on ‘Good Life’ has a lot in common with the pop production trends of the day. There are plenty of late-80s mix characteristics here – the use of dynamic range, the relatively busy arrangement and the use of frequencies (with, as we’ll see, less of an emphasis on bass than most modern mixes).

08.49 AM

Damn, what an article. Great stuff Attack.

And now I really want to hear New for U mixed like a Skirllex track. I’ll whack it through Pro L later with +30 on the gain.

01.11 PM

I would just like to say that Big Fun has greater floor impact than Look Right Through :p (played at same subjective volume of course..)

02.45 PM

Excellent Article … useful.

09.34 PM

I just want a spectrogram.

04.03 PM

i think “scary monsters and nice sprites” would sound way better as a more dynamic mix, personally. *Shrugs

03.21 PM

useful indepth article, well done to the author.

12.15 PM

Two points –

1) One thing that bugs me about the mix of the more synthetic side of dance music is how hot the highs are. Spend an afternoon with 70s vinyl: pop, rock, jazz…

I know this is media-influenced but all the mixes roll the high ends off a lot – then you come to any more modern (90s+) techno or whatnot, and the closed hats are relatively screaming at you in the mix. Sometimes I wonder if this is because everyone’s lost their hearing.

2) As a DJ primarily I’ve noticed that over the past 5 years or so, more and more dancefloor music is mastered just to be loud. This plays havoc when metering and mixing older and newer tunes, especially if you like to mix cross-genre – imagine mixing that skrillex track into Andres (just ignore the cognitive dissonance about that one). The house track’s fader will be at say 80-90% max and the other track will be at 20%. Visual metering as an aid fails. You can make it work by ear, but even then if you’re mixing kind of loud, when you relisten in a better environment, the disparity is huge.

—

I’m very pro-mp3/digital audio, but at least when you’re vinyl only, the mastering variation among songs, wrt loudness is pretty constrained.

08.26 PM

Great article!

I remember New For U was released digitally on Derrick Mays cd of the We Love Detroit compilation. If I got a copy I’d like to compare the vinyl rip with the (probably processed) digital version like the author did with Good Life

01.21 PM

Want to mix better and be able to pinpoint problem frequencies by heart? Then Train Your Ears! https://www.trainyourears.com/mixlikeapro