Back In Time

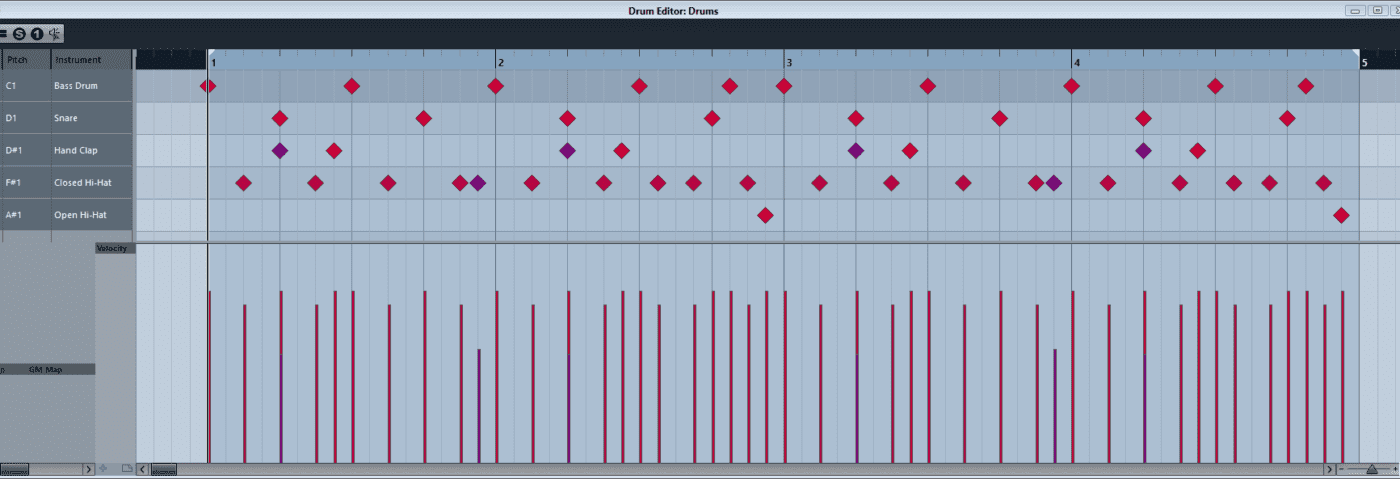

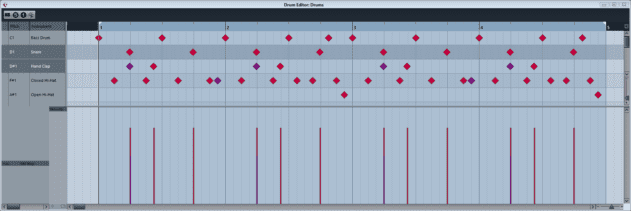

We’ve acknowledge the importance of swing already, but adjusting the timing can also utilise a broader approach. Pushing all of our kick drums forward (or pulling them back) in relation to everything else makes a lot of difference to overall feel. Here we start with a straight beat:

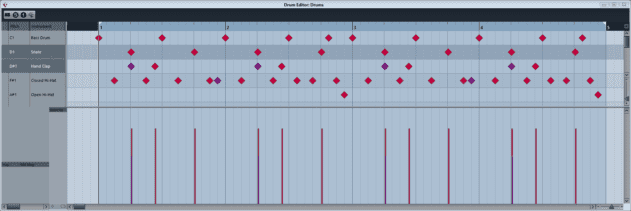

Audio PlayerThen with an early kick:

Audio Player

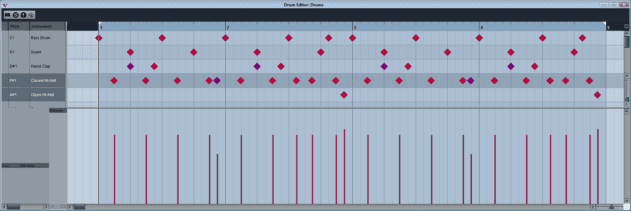

And here with a late kick:

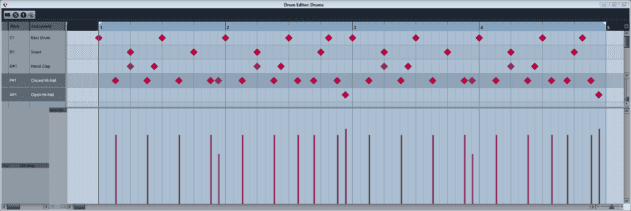

Audio PlayerBut the timing of one drum hit is only relevant when compared to other hits. The same effect is audible when we alter the timing of the snare drum, for example. Here’s how the beat sounds with an early snare:

Audio PlayerAnd then with a late snare:

Audio PlayerThe same is true with the hi-hats. Here we’ve shifter all the hats forward:

Audio PlayerAnd then the same beat with the hi-hats pushed back:

Audio Player

In fact, the same principle can be applied to any element in the track – not just drums. The relative timings of all parts affect the psychoacoustic impact of the arrangement.

Retro Feel

This brings us to an interesting point, regarding the almost mythological status of the groove imparting abilities of some drum machines and hardware sequencers. One example of an early digital drum machines was the Oberheim DMX, released in 1981. It featured separate voice boards for each sound, where the tuning would alter sample playback rate. Over the years, many people attributed a particular kind of ‘groove’ to the DMX. After much investigation (and conversations with DMX specialists Electrongate

) I discovered that this is just a by-product of the original factory bass drum sound containing a small amount of silence at the very start of the sample. This delay imparts a very ‘lazy’, dragging feel on any beat using the bass drum – and the lower the pitch the greater the drag. Interestingly, the DMX has less playback jitter than many later digital drum machines, as the individual voices are triggered in parallel.

There are many ways in which our complex auditory system makes what we hear more than just the sum of individual parts (or a literal interpretation of changes in external sound pressure level). A detailed understanding of the underlying science is not required to apply some of the ideas in a beneficial creative way, whatever your sonic taste.

09.08 AM

Absolut brilliant article!!!

But 3 soundsamples doesn’t work on page 4:

– early snare

– late snare

– early hats

cheers

09.10 AM

Thanks, Now it’s working 🙂

01.43 AM

I don’t think it’s accurate to say jitter is inherent in midi. Jitter is a much worse problem than not being able to play two notes at exactly the same time. It means that there is a degree of random inaccuracy in the timing of every single midi event. Usb midi interfaces usually have some jitter. Regular midi over a midi cable doesn’t have this issue. And expert sleepers makes a good solution for getting sample accurate midi out of a computer (via spdif, not usb).

11.34 AM

Am i completely deaf in this regard – the first two samples, no swing vs swing, sound the same to me? Can someone highlight what I should focus on here to pick up this difference?

04.12 PM

Nice! Worth reading 🙂

01.22 PM

Plyphon – the effect is quite subtle in this case but if you compare the screengrabs you’ll be able to see which hits are slightly shifted.

You can find a lot more about swing here: http://www.attackmagazine.com/technique/passing-notes/daw-drum-machine-swing/

10.26 PM

For a (good) musician it is quite obvious to vary in velocity and in pitch regardless of which instrument. Try to listen carefully to a piano pop song and you will easily hear it wether a douchbag programmed the piano or a real piano player was playing. If the douchbag programmed it, every note will have the same velocity – there is no groove and no feeling for the 1’s of a quarter.

It just feels very unnatural to play every note at the same velocity. For instance a piano player has to create groove and emphasis the first note of a quarter and fill in the dynamic ‘gaps’ if the singer is inhaling or is quiet. Try to support the first note of a quarter and make it louder than the others.

Especially drum players know much more about emphasis of notes. for example so called 3er groups.

Anyway I would recommend just try to feel the groove .. listen carefully and stop thinking just let your foot decide wether it’s good or bad way you set the accents / emphasis.

Good example of techno with emphasis:

https://soundcloud.com/pinkmanrecords/pnkmn08-annanan-antagonism-ep

10.38 PM

Don’t forget that changing the pitch of a sample doesn’t just change the perceived loudness in terms of sample length, it also changes the perceived loudness based on the change in frequency content. It’s a psychoacoustic effect and the reason why 20 Hz and 16+ kHz seems quiet but the frequencies between, especially 2-3kHz, seem louder. The sample may be shorter when you pitch it up, but the perceived loudness could increase or decrease based on the sound level and position in the Fletcher-Munson curves.

07.09 AM

Danny – yes that’s right. However, most of the pitch changes used for the drums here are very small, so I don’t think the effect will particularly noticeable in this instance.