There are so many different types of EQ, how do you know which one is right? In this tutorial, we break down some common types of EQ and highlight when to use them.

If you always reach for the same EQ no matter the sound source or situation, you may be doing your mix a disservice. While there’s nothing wrong with using a general EQ for most applications, it’s possible that you could get better results from a different kind. And there are even cases where a standard EQ could be hurting things.

In this beginner’s guide to EQ, we’ll look at some of the most common types of EQ and when and how to best use them. Note that it’s not intended to be an exhaustive list. As always, click on any image to see a larger version.

What Is EQ, Anyway?

This may seem an obvious question but just to avoid confusion, let’s address what an EQ is. An equalizer is essentially a filter. It allows you to adjust the volume level of frequencies in an audio signal, either by boosting (raising the volume) or cutting (lowering the volume).

Most equalizers that we use in music production are parametric EQs. These provide continuous control over the centre frequency to be adjusted as well as bandwidth, or how wide the change is. It also allows you to adjust the Q, which is the ratio of the centre frequency to bandwidth. For comparison, graphic EQs (the kind you find on stereo equipment) have set frequencies and no Q control.

Equalizers usually have notch and shelf filters. Notch filters are the ones that you use in the middle of the frequency band and are represented by a bell curve. Shelf filters (also called high- and lowpass filters) are for cutting all frequencies below or above the cutoff point.

Now that we have our basics out of the way, let’s look at five types of EQ. We’ll organize them into two broad categories: modern and vintage.

Modern

Modern EQs are powerful, transparent, and capable of making surgical changes that just were not possible in the hardware days. And, with their visual component, it’s easy enough to see the target frequencies as well as hear them. Modern EQs include the kind that come stock with your DAW as well as more specific types such as linear phase and dynamic.

Digital

Best for: General applications, surgical cuts and boosts, transparency

Modern digital EQs are what we usually reach for when mixing. They provide continuous control over frequency and offer surgical precision for cutting and boosting. Digital EQs are also transparent, meaning they won’t colour your sound. They often come stock with your DAW or can be bought separately, such as Waves’ H-EQ, which we’re using.

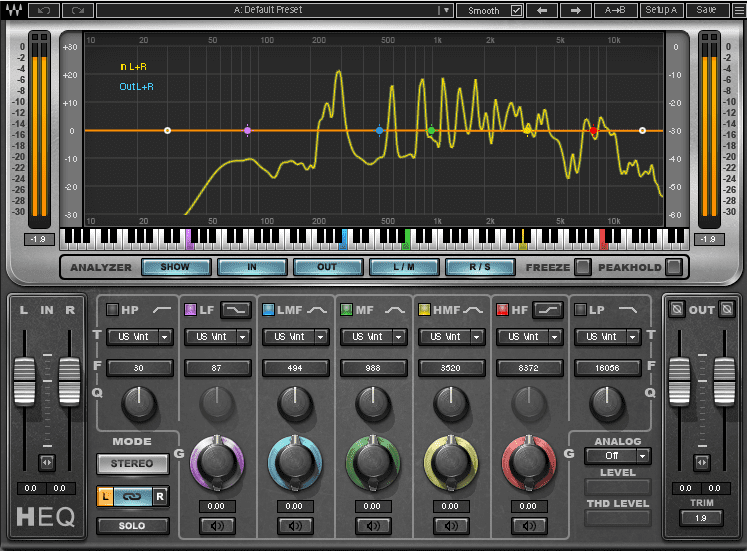

As this is the EQ type that most people are already familiar with, we won’t spend too much time on it, but suffice it to say that digital EQs are great for surgical cuts and boosts, and for when you need precise control over frequencies.

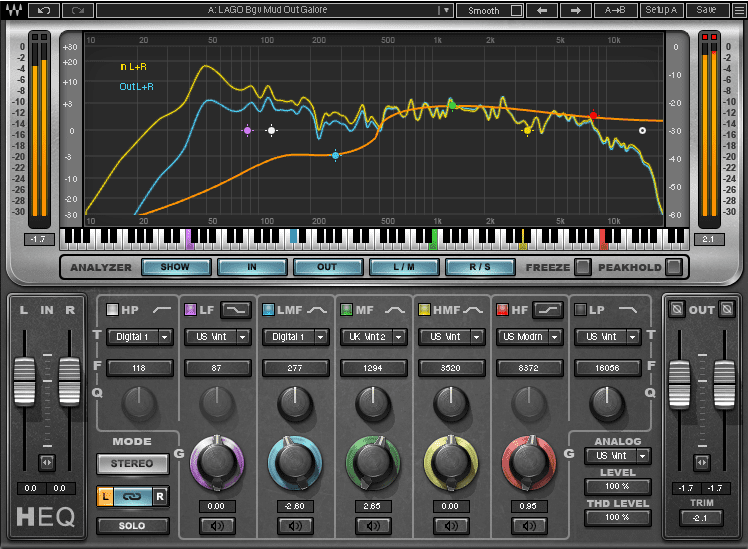

Here we’re using H-EQ to do some tone-shaping on a drum loop, ‘US_WT_125_Drumloop_Concrete_STP’, from UNDRGRND Sounds’ Warehouse Techno pack. We like the loop but want to use it as a top, so we lower the bass at 500Hz and shelf it off below 200Hz. We also use it to boost the mids and highs.

Before EQ:

And after EQ:

Linear Phase

Best for: Narrow notches and steep filters, parallel EQing, mastering

Standard equalizers, also known as minimal phase EQs, introduce a small amount of phase shifting and harmonic smearing around the part of the sound they’re changing. This can be musically pleasing and is often what gives an equalizer its ‘sound’. Most of the time, this is unnoticeable and won’t affect the sound in a negative way.

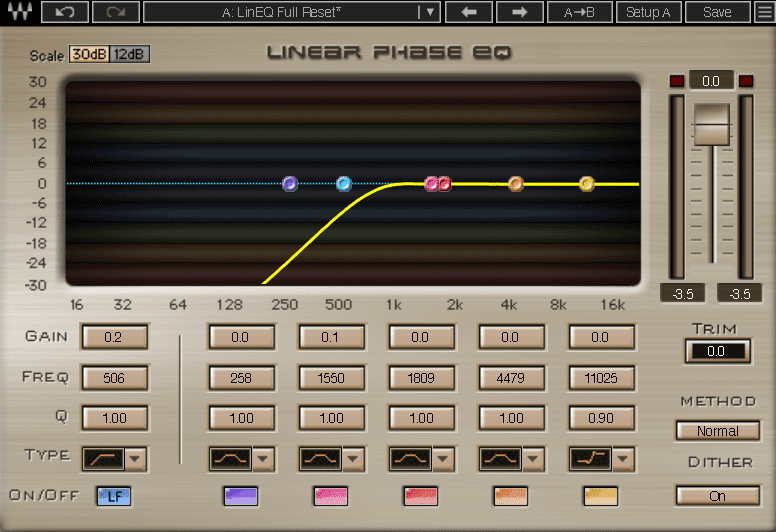

However, in some cases, a regular EQ could introduce phase cancellation and cause frequencies to decrease in volume or disappear from the sound. When this happens, you need to use a linear phase equalizer instead. By delaying the entire sound simultaneously, linear phase EQ eliminates this problem. This makes it ideal for working with parallel channels (particularly when using a shelving EQ) or other times when phase shift issues might be present.

Linear phase can be found as a mode in many EQs as well as in dedicated plugins, like Waves’ Linear Phase EQ.

Here, we’ve got the vocal sample, ‘120_Bm_Tonight_01_TL’, from Touch Loops’ Soul Voices sample pack, duplicated onto two audio channels. We highpass the second version to create parallel EQ and emphasize the highs and mids. When we use the minimal phase H-EQ, we lose quite a bit of the frequencies around the cutoff point, but when we use the same EQ curve in Linear Phase EQ, we can hear that there is no phase cancellation between the two samples.

We’d like to point out that phase cancellation isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as we highlighted in ‘5 Mixing Rules You Should Be Breaking’. It all depends on what you want to achieve.

Top Tip: Linear phase EQ won’t work in all cases. It’s best to avoid it on single elements with heavy transients. Because the audio has been shifted forward and then compensated for by your DAW, it can cause pre-ringing. This sounds almost like backwards reverb leading up to the transient. It’s best to listen carefully to any audio signal when using linear phase EQ to make sure you’re not doing more harm than good.

Minimal phase EQ:

Linear phase EQ:

Dynamic

Best for: Frequency-masking issues

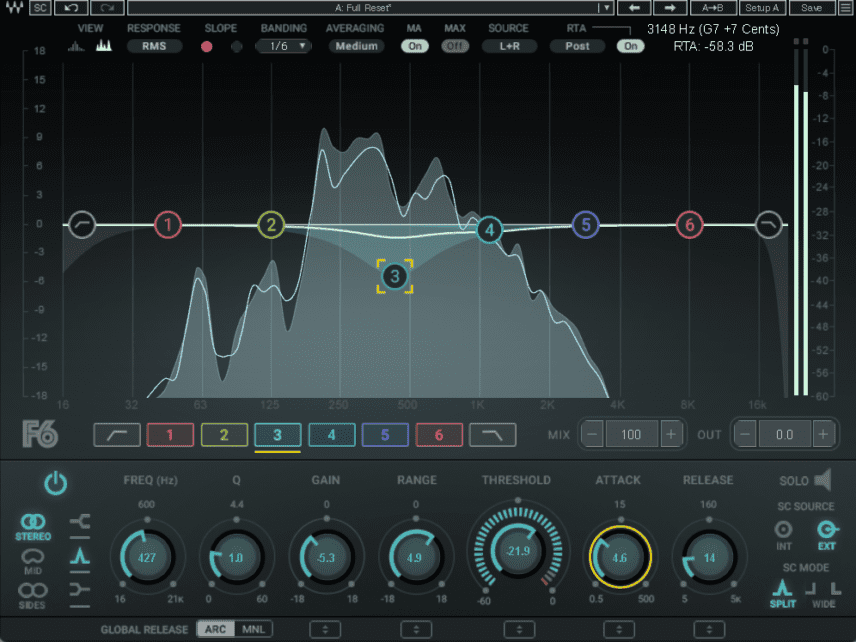

Dynamic EQ adds a sidechain element to EQing, making it an incredibly convenient and powerful way to target frequencies. Instead of affecting overall volume, as with sidechain compression, dynamic EQ responds to incoming audio to cut (or boost) a specific frequency band. When the sidechained audio isn’t present, the EQing stops. As you can imagine, this makes it perfect for handling masking jobs.

Let’s use Waves’ F6 Floating-Band Dynamic EQ to help two audio channels sit together. Here we have our vocal sample from before as well as some chords from the sample ‘125_Bm7_Lo-Fi-Chords_TL’, taken from Touch Loops’ Lo-Fi House Chords pack. There’s considerable frequency overlap between the two. As we want to help the vocal stand out, we need to carve out some frequencies from the keys in the mid-range. We could do this with a normal EQ but we’d still be left with a big frequency hole in our chords when the vocals aren’t audible. With dynamic EQ, we can have the best of both worlds: room in the vocal and full keys during the instrumental sections.

We can clearly hear frequency overlap between the vocal and chords here:

Now with dynamic EQ applied:

Vintage

Vintage-style EQs are largely based on famous pieces of hardware. Where modern, digital EQs are transparent and surgical, vintage-style EQs offer colour and broad tone-shaping functionality. Much like compressors, there are plenty of famous hardware EQ units, both old and new, as well as emulations. Each has its own unique sonic footprint as well as frequency bands that it works best with. The vintage-style EQ you choose will largely be down to the colour and frequency range you want to affect.

Channel Strip

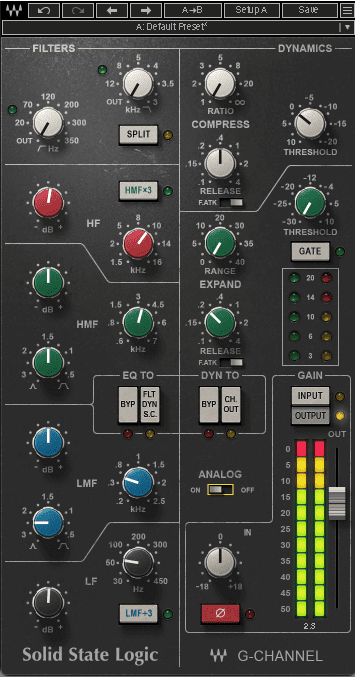

Best for: Making broad frequency adjustments on individual channels or busses

In the days before DAWs (and in some very well equipped studios to this day), mixing engineers relied on the EQ on their mixing boards to make tonal adjustments. Each channel had a limited set of pots to adjust frequency (within a restricted band), cut or boost in decibels, and Q width. Some also had shelving controls. When used across the board, they added small amounts of colour to each channel, which build up subtly over the entire mix. (It’s also great for getting mixer-style distortion.)

Let’s use SSL G-Channel, Waves’ recreation of the channel strip EQ in Solid State Logic SL 4000 console, to see how this sounds. We’ve added it to every channel, including to a new drum loop, ‘US_WT_127_Drumloop_Orbit_stp’, from Warehouse Techno by UNDRGRND Sounds. We also put SSL G-Channel on the master bus. We’ve ignored the dynamics section and mostly used it to add air at the top and a little extra bass weight on the drum loop. Engaging the Analog mode across all channels helps add cohesion to the sound.

Without channel EQ:

With channel EQ:

Pultec

Best for: boosting bass and adding air

Pultec (short for Pulse Technologies) is a series of EQs first manufactured in the 1950s. They used a passive circuit, which meant that the EQ portion of the unit didn’t require any power, as well as a tube-based amplifier to bring the audio level back up. This translated into improved sound and colour that is still sought after 60 years later.

The most famous of the Pultec EQs was the EQP-1, which offered only low or high band adjustments. The high band is perfect for dialling in extra air and sparkle while the low bands feature what has become known as the ‘Pultec bump’. Unlike other EQs, the EQP-1 allows you to both cut and boost the same frequency. While this seems contradictory, in reality, the unit spreads the boost and cut points apart, yielding a nice low bump with a scoop above it. As you can imagine, this is perfect for kick drums, giving you both a bass boost and a mid-bass cut.

Let’s use the same drum loop from the SSL demonstration and Waves’ PuigTech EQP-1A to see how this works. We boost and attenuate at 100Hz while also adding a generous helping of highs at 12kHz. The analogue-style circuit is also adding character and colour. The difference is clearly audible.

Before the Puigtech EQP-1A:

And with the EQ engaged:

*Attack Magazine is supported by its audience. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Learn more.